Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

Signed at lower right: “·ABoʃ_chaert· / 16__”

Entry

-

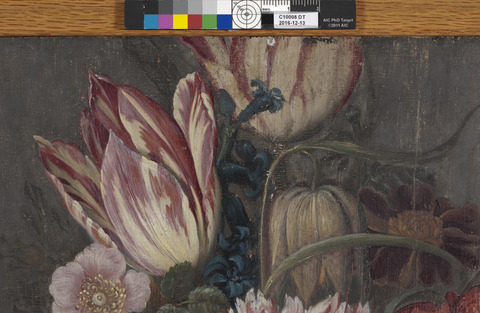

French rose (Rosa gallica semiplena)

-

tapered tulip hybrid (Tulipa armena x cf. T. hungarica)

-

lady-in-a-mist (Nigella damascena semiplena)

-

lavender cotton foliage (Santolina chamaecyparissus)

-

carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus plenus bicolor)

-

snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis)

-

poppy anemone (Anemone coronaria purpurea)

-

sweet briar (Rosa rubiginosa)

-

tapered tulip hybrid (Tulipa armena x cf. T. stapfii)

-

hyacinth (Hyacinthus orientalis)

-

Iberian fritillary (Fritillaria lusitanica)

-

French marigold (Tagetes patula)

-

red turban cap lily (Lilium chalcedonicum)

-

pansy (Viola tricolor)

-

meadow brown [butterfly] (Maniola jurtina)

-

sand lizard (Lacerta agilis)

-

greenbottle fly (Lucilia caesar).2

Author

Provenance

John Kenneth Danby (1889–1956), Wilmington, Delaware;

Sale at (Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York) in 1956.32

(Victor D. Spark, New York), probably in 1956;

Edith Whitehill Clowes (1885–1967), Indianapolis, in 1958;33

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2019, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10008);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2019.

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1958, The Young Rembrandt and His Times, no. 78;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 8;

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, 1963, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 39.

References

David G. Carter, The Young Rembrandt and His Times, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1958), no. 78 (reproduced);

David G. Carter, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), no. 8 (reproduced);

F.W. Bilodeau, “The Clowes Fund Collection at Indianapolis, Indiana,” The Connoisseur 148, no. 595 (August 1961): 8;

Henry R. Hope, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, exh. cat. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Museum of Art, 1963), no. 39;

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), xxxvi, 86–87 (reproduced);

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, 100 Masterpieces of Painting: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 117 and 118 (reproduced);

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, Handbook of European and American Paintings to 1945: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1981), unpaginated (reproduced).

Amanda Weiss, “Seventeenth-Century Dutch Still Life and the Bosschaert Painters: Is There a Real Art of Tulip Mania?” Bowdoin Journal of Art 3 (2017): 17 (reproduced).

Notes

-

Since the cleaving of the identity and the oeuvre of Ambrosius II from his father in 1935, Ambrosius II has been considered the eldest of Ambrosius I’s three sons. Documents indicate that Ambrosius II was baptized on 1 March 1609 in Arnemuiden; see L.J. Bol, “Een Middelburgse Brueghel-groep,” Oud Holland 70, no. 1 (1955): 17, and more broadly, L.J. Bol, “Een Middelburgse Brueghel-group. IV. In Bosschaerts Spoor (vervolg).” Oud Holland 71 (1956): 140–148. All three sons practiced the art of painting, but the loss of documents in the Middelburg archives has made confirmation of their ages almost impossible. The informal description of the family by Ambrosius I’s daughter, Maria Sweerts, lists Ambrosius II first, followed by his brothers Johannes and Abraham. Scholars have interpreted this arrangement as one according to age, from eldest to youngest. A recent refiguring of the history of the Bosschaert family by Fred Meijer, however, has posited that Ambrosius II was the second of the three sons. See Abraham Bredius, “De Bloemschilders Bosschaert,” Oud Holland 31, no. 2 (1913): 137–140, and Fred G. Meijer, Stillevens uit de Gouden Eeuw: Eigen collectie Museum Boymans-van Beuningen Rotterdam (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1989), 60–61. ↩︎

-

I would like to thank Irvin Etienne of Newfields' horticulture department for an informative orientation to these flowers in September 2013. The late Sam Segal generously identified the flowers in email dated 9 October 2013. ↩︎

-

On the chiaroscuro of hue, see Paul Taylor, “The Concept of Houding in Dutch Art Theory,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 55 (1992): 229–230, and Paul Taylor, Dutch Flower Painting, 1600–1720 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995), 112. ↩︎

-

Sam Segal, upon seeing the painting in 1987, read the year as “1629.” (See object number 122889 in the RKDImages Database at the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, https://rkd.nl/explore/images/122889, accessed 5 May 2021.) The appearance of several dated paintings on the market in recent years has rendered Laurens J. Bol’s system of dating according to variations in the artist’s signature insufficient. See L.J. Bol, The Bosschaert Dynasty: Painters of Flowers and Fruit (Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, 1960), 44, and Adriaan Van der Willigen and Fred G. Meijer, A Dictionary of Dutch and Flemish Still-life Painters Working in Oils, 1525–1725 (Leiden: Primavera Press/RKD, 2003), 46. ↩︎

-

The dendrochronological report of Peter Klein, dated 21 June 1999, indicates the earliest possible year of creation as 1634. See File C10008, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Published technical investigations of Ambrosius II’s work are rare. The most useful study is Sarah Murray and Karin Groen, “Four Early Dutch Flower Paintings Examined with Reference to Crispijn de Passe’s Den Bloem-Hof,” Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, no. 2, ed. A. Massing (Cambridge: University of Cambridge, Hamilton Kerr Institute, 1994): 6–204. ↩︎

-

For a comprehensive analysis, see the Technical Examination Report. ↩︎

-

Paintings by both Ambrosius I and his influential son-in-law Balthasar van der Ast display multiple roses in the lower part of the bouquet. See, for example, Ambrosius I’s paintings in the Mauritshuis in The Hague (inv. no. 679) and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (inv. no. A539), and Van der Ast’s flower piece in the Gemäldegalerie in Dessau (RKDImages Database, object no. 119945). ↩︎

-

See the painting of 1626 that was with Salomon Lilian in 2002 (RKDImages Database, object no. 25637), a painting of 1632 formerly with Terry-Engell Gallery in London (RKDImages Database, object no. 122900), and in a painting of about 1635–1640 in the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge (inv. PD.59-1974), among others. ↩︎

-

On the so-called tulip mania, see Anne Goldgar, Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), particularly chapter 2. ↩︎

-

On this discovery, see Fiona Beckett and Gregory Dale Smith, “Restoring a ‘Broken’ Tulip: Analysis-Informed Conservation Treatment of Ambrosius Bosschaert’s 17th-Century Floral Still Life,” Conservation 360 2 (2020). In a draft of this article (and in the 2017 exhibit at the IMA about the newly uncovered tulip), the authors identify this variegated tulip as the Semper Augustus variety. As there were several types of highly valued red-and-white broken tulips in the seventeenth century, as documented in The Great Tulip Book in the Norton Simon Museum (M.1974.08), this newly uncovered tulip cannot be called Semper Augustus with any degree of certainty. ↩︎

-

Printed examples, in the form of illustrations in botanicals and florilegia, would likely have been inadequate prototypes for the colorful bouquets executed by the Bosschaert dynasty. As Sarah Murray and Karin Groen discuss in “Four Early Dutch Flower Paintings Examined with Reference to Crispijn de Passe’s Den Bloem-Hof,” Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, no. 2, ed. A. Massing (Cambridge: University of Cambridge, Hamilton Kerr Institute, 1994): 6–204, however, Van de Passe’s Den Bloem-Hof of 1614, specifically its chapter titled “Beschriivinghe van de Couleuren der vier deelen des Bloem-boecx, ende hoemen de selve met hare eyghen Verven sal mooghen schilderen ofte afsetten,” may have offered some guidance as to which pigments to use for specific flowers. Though its illustrations are in black and white, there are several pages of descriptions of the colors of the flowers and their leaves. By the sixteenth century, working after nature had become particularly important. Leonard Fuchs’s De historia stirpium (about 1542) contains an illustration in which artists draw after a bouquet on a sheet and on a woodblock, suggesting the fidelity to nature of the plants illustrated in his volume. For this woodcut illustration, see Beatrijs Brenninkmeyer-de Rooij, Roots of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Flower Painting: Miniatures, Plant Books, Paintings (Leiden: Primavera Pers, 1996), fig. 30. Interestingly, no carbon-based underdrawing was found in the present painting using infrared reflectography, according to Sarah Gowen’s report of 1 August 2013. Given how frequently Ambrosius II repeated motifs from painting to painting, he must have laid in the composition using red or brown pigments that do not register in infrared. ↩︎

-

See Meghan Siobhan Wilson Pennisi, “The Flower Still-Life Painting of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder in Middelburg, c. 1600–1620,” PhD diss., Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 2007, 192. Gerard de Lairesse, the first Northern painter-theorist to write substantially about flower paintings, recommends that artists organize these studies into separate boxes according to color. See Lairesse Gerard de Lairesse, Groot Schilderboek, 2 vols. (Haarlem: J. Marshoorn, 1740), 2:367. ↩︎

-

Dutch private collection; RKDImages Database, object no. 122893; and private collection. See Noortje Bakker et al., Masters of Middelburg: Exhibition in Honour of Laurens J. Bol, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Kunsthandel K. & V. Waterman, 1984), no. 24, and RKDImages Database, object no. 184379. ↩︎

-

See Erika Gemar-Koeltzsch, Luca Bild-Lexikon: Holländische Stillebenmaler im 17. Jahrhundert, 3 vols. (Lingen: Luca, 1995), 2:172, cat. no. 52/3 and the Fitzwilliam Museum (inv. no. PD.18-1973). ↩︎

-

See L.J. Bol, The Bosschaert Dynasty: Painters of Flowers and Fruit (Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, 1960), 65, cat. nos. 17 and 13. ↩︎

-

For the painting in the possession of Johnny van Haeften, see Erika Gemar-Koeltzsch, Luca Bild-Lexikon: Holländische Stillebenmaler im 17. Jahrhundert, 3 vols. (Lingen: Luca, 1995), 2:51, cat. no. 8/11, and RKDImages Database, object no. 49631. On the Berlin painting, see L.J. Bol, The Bosschaert Dynasty: Painters of Flowers and Fruit (Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, 1960), 79, cat. no. 71, and RKDImages Database, object no. 120039. For an undated panel with the lizard, see Laurens J. Bol, “Goede Onbekenden”: Hedendaagse herkenning en waardering van verscholen, voorbijgezien en onderscht talent (Utrecht: Tableau, 1982), 54, fig. 3. A study of a sand lizard from Van der Ast’s Delft period survives in the Lugt Collection, inv. no. 6534–53; see RKDImages Database, object no. 120471. ↩︎

-

Meghan Siobhan Wilson Pennisi, “The Flower Still-Life Painting of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder in Middelburg, c. 1600–1620,” PhD diss., Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 2007, 189. ↩︎

-

For a recent comparative approach, see Amanda Weiss, “Seventeenth-Century Dutch Still Life and the Bosschaert Painters: Is There a Real Art of Tulip Mania?” Bowdoin Journal of Art 3 (2017): 1–35. ↩︎

-

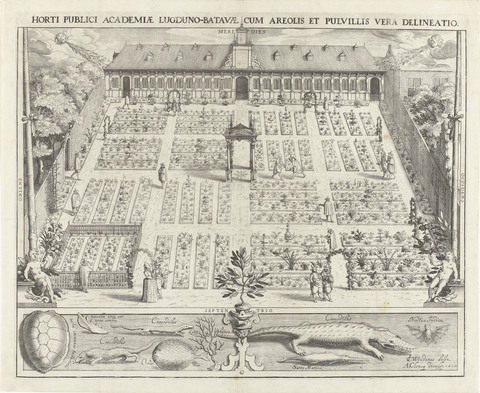

On the shift of the garden from a medieval site of pharmaceutical and culinary cultivation to its Renaissance conception as a botanic location, see W. De Backer et al., Botany in the Low Countries (end of the 15th century–ca. 1650), exh. cat. (Antwerp: Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, 1993); Meghan Siobhan Wilson Pennisi, “The Flower Still-Life Painting of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder in Middelburg, c. 1600–1620,” PhD diss., Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 2007, 76–87; and Claudia Swan, “Of Gardens and Other Natural History Collections in Early Modern Holland: Modes of Display and Patterns of Observation,” in Museum, Bibliothek, Stadtraum. Räumliche Wissenordnungen 1600–1900, ed. Robert Felfe and Kirsten Wagner, Kultur: Forschung und Wissenschaft 12 (Berlin: Lit, 2010), 173–190. ↩︎

-

It is highly unlikely that flowers would have been cut for display in the home, as is practiced today. This assertion stems from J.G. van Gelder’s observation that very few cut bouquets appear in genre paintings of the seventeenth century, as this would have severely diminished their value. See Lawrence O. Goedde, “A Little World Made Cunningly: Dutch Still Life and Ekphrasis,” in Still Lifes of the Golden Age: Northern European Paintings from the Heinz Family Collection, ed. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1989), 43n15. Rather, it seems that the appearance of bouquets in seventeenth-century portraits conveys a symbolic, often vanitas, meaning, as in Peter Paul Rubens’s The Four Philosophers (1611–1612, Florence, Pitti Palace, inv. 85). ↩︎

-

Claudia Swan, Art, Science, and Witchcraft in Early Modern Holland: Jacques de Gheyn II (1565–1629) (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 67–68, and Anne Goldgar, Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 120–123. ↩︎

-

Peter Mitchell, European Flower Painters (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1973), 16. ↩︎

-

Sam Segal, De tulp verbeeld. Hollandse tulpenhandel in de 17de eeuw (Amsterdam: Museum voor Bloembollenstreek, 1992), 2. ↩︎

-

Abbreviated English translation from L.J. Bol, The Bosschaert Dynasty: Painters of Flowers and Fruit (Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, 1960), 18. The full original Dutch sentences are: “Ick seynde u.E. mits desen het contrefeytsel van een seeckere soorte van Tulipan van gelijcke groote, ende hoochde, van bolle, steele, en blomme ende andersins also u.E. dat tegenwoordich siet, alleen sijn die bladers lanckwerpiger ende smal. Want ik datselve soo nauwe hebbe doen afsetten als mogelijk was, ooc den bolle ontbloot op dat hem de schilder mochte sien.” See F.W.T. Hunger, “Acht brieven van Middelburgers aan Carolus Clusius,” Archief: Mededelingen van het Koninklijk Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen (1925): 111–112. ↩︎

-

“Ick sende uwe E. de contrefeytsel vande gelluwe fritelaria die dit jaer in dier vougen in mijnen hoff heeft gebloyt, die seer schoon staat om te sayen.” See F.W.T. Hunger, “Acht brieven van Middelburgers aan Carolus Clusius,” Archief: Mededelingen van het Koninklijk Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen (1925): 127. ↩︎

-

Other early influences include botanical illustrations and miniatures from books of hours. See, for example, Sam Segal, De tulp verbeeld: Hollandse tulpenhandel in de 17de eeuw (Amsterdam: Museum voor Bloembollenstreek, 1992), 3–11; W. De Backer et al., Botany in the Low Countries (end of the 15th century–ca. 1650), exh. cat. (Antwerp: Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, 1993); and Beatrijs Brenninkmeyer-de Rooij, Roots of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Flower Painting: Miniatures, Plant Books, Paintings (Leiden: Primavera Pers, 1996), 11–44. ↩︎

-

L.J. Bol, The Bosschaert Dynasty: Painters of Flowers and Fruit (Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, 1960), 17. ↩︎

-

The highest price paid was a legendary 13,000 guilders for a single Semper Augustus bulb. See Paul Taylor, Dutch Flower Painting, 1600–1720 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995), 10. ↩︎

-

I.Q. Van Regteren Altena, Jacques de Gheyn: Three Generations, 3 vols. (The Hague, Boston, and London: Martinus Nijhoff, 1983), 1:85, 2: no. IIP 38. ↩︎

-

L.J. Bol, “Een Middelburgse Brueghel-groep,” Oud Holland 70, no. 1 (1955): 18. ↩︎

-

Following Danby’s death, his estate was put up for auction; see Important American Furniture and Decorations, American and British Portraits and other painting: Property of the Estate of the Late John Kenneth Danby, Wilmington, Del., part one, sale cat., Parke-Bernet, New York, 11–13 October 1956, no. 345, as Vase of Flowers by Ambrosius Brueghel. ↩︎

-

Receipt of Sale, 16 April 1958, File C10008, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. See also Letter from David G. Carter to Victor D. Spark, 1 April 1958, File David G. Carter [19]57–58, Administration/Registration T.A.B.2005.110, Indianapolis Museum of Art Archives at Newfields. ↩︎