Building the Clowes Collection

Kjell M. Wangensteen, PhD

Associate Curator of European Art

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields

Assembled largely, though not exclusively by a single individual, the Clowes Collection now forms the nucleus of the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s permanent collection of European art.1 Comprising 105 Old Master paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and objets d’art, its contents span more than six centuries and encompass nearly every major European artistic school. It has been the subject of numerous exhibitions and publications over the past six decades, including exhibitions in 1959, 1962, 1963, 1965, and 1967, with a summary catalogue published in 1973.2 The fairly limited scope of these efforts tends to give an impression of the Clowes Collection as a static entity and completed project, reflecting the interests and intentions of its creator, Dr. George Henry Alexander Clowes (1877–1958). These works function as “snapshots,” in a way, of a particular moment in the collection’s development—1958, to be precise, the final year of Clowes’s life.

While it is certainly true that the Clowes Collection bears the imprint of the man himself, personal collections like his are almost never a fait accompli, but always a work in progress, continually evolving and changing as new opportunities present themselves and personal taste evolves. In most cases, the collection continues to grow and develop long after the death of its originator. The Clowes Collection is an excellent case in point, as it was further augmented and shaped by Clowes’s wife, Edith Whitehill Clowes (1885–1967), and his younger son Allen (1917–2000), in the decades after the death of Dr. Clowes.

Drawing from the rich trove of archival material preserved at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Indiana Historical Society, and the archives of Eli Lilly and Company, this essay examines the formation and development of the Clowes Collection over the course of its nearly century-long history, from Dr. Clowes’s first purchases to its final disposition as part of the IMA’s permanent collection.3 This broadened perspective allows fora deeper understanding of the growth and evolution of a major American art collection, and of the remarkable story of Dr. Clowes and his family, whose legacy lives on in the exceptional collection that bears their name.

Dr. George H.A. Clowes, Scientist and Innovator

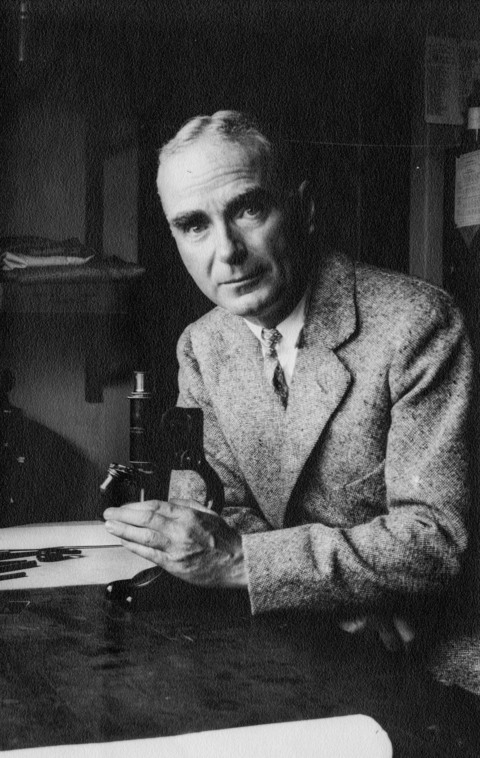

Respected in scientific circles around the globe but known affectionately to his colleagues as “Doc,” George H.A. Clowes was many things at once: a world traveler, a generous philanthropist, a music lover, a devout churchgoer, and a passionate art collector (fig. 1). He was the rare individual who combined the left-brained, analytical tendencies of the research chemist with the right-brained, aesthetic sensibility of the art lover. Endowed with a boundless well of energy and unbridled optimism, he also manifested a penchant for calculated risk-taking in pursuit of his goals in the scientific sphere and beyond. One might even say that his dogged pursuit of great masterpieces mirrored his lifelong search for solutions to the thorniest scientific problems. Above all, unremitting effort and unwavering commitment played a crucial role in his success. In a report to Eli Lilly and Company’s management, he once noted that “The conduct of research is just as much a matter of accurate information, organization, foresight, imagination, and tenacity of purpose, as is that of any other enterprise."4 Recalling Clowes’s intensity and zeal, J.K. Lilly remarked, “[Clowes] lived more hours per day than any man I ever knew."5

Though his surname is now associated with numerous institutions in Indianapolis, Clowes himself was very much a product of Victorian England. Born in 1877 into a respectable family of merchants and clergymen in Ipswich, Suffolk, he distinguished himself in mathematics and science from an early age, and thereafter pursued the study of chemistry at the Royal College of Science in London. As German universities stood at the forefront of scientific research, Clowes decided to pursue graduate work at the University of Göttingen, from which he received his doctorate in 1899.

Trained as a research chemist, Clowes nevertheless found himself attracted to fundamental questions that intersected with the realm of medicine. With his penchant for promising (if risky) avenues of inquiry, Clowes decided to focus on cancer research, a field that was still in its infancy. In 1900, he accepted a research position at the Gratwick Laboratory in Buffalo, New York (now called Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center). There he pioneered new chemical approaches to chemotherapy, demonstrating its potential as a treatment for cancer.6 Over the course of the next 18 years, Clowes earned a reputation as an earnest and hardworking scientist, generally respected for his willingness to tackle the most difficult research problems.7

At the time, Buffalo was a rising industrial city of 350,000 inhabitants and home to the greatest number of millionaires per capita in the world. There, Clowes quickly settled in among the elegant mansions, leafy boulevards, and social clubs of Delaware Avenue. When not in the laboratory, he occupied himself with outdoor activities of all sorts, from horseback riding to dancing and ice skating. He made the acquaintance of a local doctor, Frank Whitehill Hinkel, whose daughter Edith had returned from an extended tour of Europe and two years of study at Vassar College. Clowes began courting her, and the two were married in 1910. The pair settled into a comfortable life and started a family, with two sons, George Jr. and Allen, born in 1915 and 1917, respectively.

With the outbreak of World War I, Clowes volunteered to assist the US Chemical Warfare Department. As a British citizen, however, he was required to serve in a civilian unit rather than a military one. (He became a naturalized US citizen in 1921.) In 1918, he began conducting research at the American University Experiment Station in Washington, DC, and at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

By this time, Clowes was a seasoned and established research chemist, and it was largely due to his reputation within the international scientific community that he received an offer that would change his life. In November 1918, he was invited to Indianapolis by J.K. Lilly, Sr., president of the pharmaceutical firm Eli Lilly and Company. Capitalizing on a nationwide shortage of German-made pharmaceutical products during the war, the company was poised to undertake a total reorganization in pursuit of a costlier and riskier strategy, but one that promised greater long-term rewards. Rather than producing less-profitable generic drugs, Eli Lilly and Company would begin conducting basic scientific research to develop new pharmaceuticals for the US market. Reflecting back on his eagerness to work on the frontiers of scientific research, Clowes noted that this role suited him perfectly.8

In the spring of 1919, Clowes moved his family to Indianapolis and joined Eli Lilly and Company as a staff biochemist. He flourished there from the start: just one year later, he took the helm as the company’s director of research. Writing to a colleague, Clowes rhapsodized, “for the first time in my life, I am free to devote my attention to those fundamental problems on the border line field of physics, chemistry, biology and medicine, in which, as you doubtless know, I have long been interested."9 Eager to please his newest hire, J.K. Lilly, Sr. agreed to make a laboratory and staff available to Clowes at Woods Hole, where the scientist and his family would spend the summer months for the rest of his life. Lilly saw a huge opportunity in hiring a scientist of Clowes’s ability and reputation, writing to his sons that Clowes would “someday hit some great thing that will make him famous and rich."10

Thus began the most important era in the firm’s history, and, according to Clowes, “the most strenuous, and the happiest, and certainly the most interesting period of my life."11 He devoted himself to the work, regarding it as essential for Eli Lilly and Company to secure the “recognition, respect and confidence of scientific and medical organizations and individuals all over the world” in order to attract the most promising scientists and thereby succeed in developing new pharmaceuticals.12 Accordingly, he maintained close ties with members of his scientific network, keeping abreast of new discoveries and potential avenues of research.

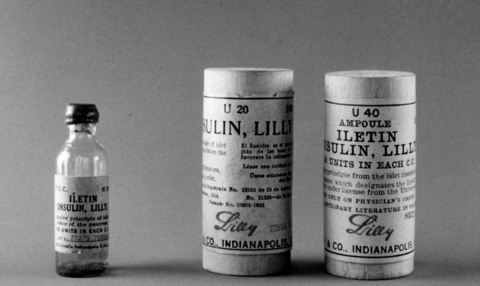

Little could he have realized how important such connections would be. On Christmas Day, 1921, Clowes boarded a train to New Haven, Connecticut, where a team of researchers from the University of Toronto would present their findings on a potential treatment for diabetes mellitus to the American Physiological Society. Among those presenting were Frederick Banting and Charles Best, who were collaborating with J.J.R. Macleod to study a hormone derived from pancreatic secretions. Clowes immediately grasped the hormone’s potential as a therapeutic treatment, and doggedly pursued a partnership with the Canadian team. Though the Canadians were initially reluctant to commercialize their research, Clowes’s high standing in the scientific community and Eli Lilly and Company’s considerable resources helped persuade them otherwise. On 22 May 1922, Clowes signed an agreement with the Toronto researchers granting Eli Lilly and Company exclusive license to develop, produce, and sell Iletin, the hormone known today by its generic name, insulin.

Developing this hormone into a new drug was not possible at the time, however, as there was no way to produce it on an industrial scale. Clowes and his colleagues concentrated their efforts on the production problem, and by the spring of 1923 the company had engineered a new isoelectric precipitation process that allowed for its extraction and mass production.13 This paved the way for the distribution and sale of the world’s first commercially available treatment for diabetes that revolutionized its treatment and has saved millions of lives since its introduction a century ago (fig. 2).

Clowes’s scientific gamble paid off spectacularly. The commercial success of insulin made Eli Lilly and Company a household name, and the firm would go on to produce other innovative and successful drugs, including the polio vaccine and penicillin. Almost overnight, Clowes became wealthy beyond his wildest imagination, allowing him to indulge his passion for collecting art in the decades that followed.

Clowes the Collector

Clowes pursued great works of art for his collection with the same single-minded determination and precise, analytical frame of mind that made him a successful research scientist. In restricting his acquisitions to works by the Old Masters, he followed the examples of other self-made American art collectors like the chemist Albert C. Barnes (1872–1951), the retail magnate Samuel H. Kress (1863–1955), and his fellow Indianapolitan, the eminent writer Booth Tarkington (1869–1946). Like them, Clowes had no training in art history. What he lacked in formal education, however, he compensated for with his characteristic fervor, diligence, and enthusiasm.

He also began collecting at a propitious moment. As the Great Depression reduced the financial circumstances of old aristocratic families in Europe, many were forced to sell off their art treasures to collectors abroad. While a previous generation of collectors like J.P. Morgan (1837–1913) and Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919) had already established the stereotype of the “acquisitive American,” Clowes and his contemporaries had the added advantage of several well-connected art dealers based in the United States who catered to well-heeled neophytes like himself. Chief among them were the New York firms E. and A. Silberman Galleries and Newhouse Galleries.

It is interesting to note, however, that Clowes began his collecting career as a bibliophile rather than as a collector of paintings. His very first purchases consisted of several illuminated manuscripts bought in the spring and summer of 1930 from various book dealers in London and Florence, four of which are now at the IMA.14 They include a fourteenth-century Dominican missal and three fifteenth-century illuminated books of hours.15

It is hardly surprising, then, that one of Clowes’s very first purchases of a work of art, on 14 January 1933, was from the owner of a bookshop located on Monument Circle, in the heart of Indianapolis (fig. 3).16 The striking portrait, then attributed to the English portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds (now considered to be a work of his circle), may have appealed to Clowes for its English origins, or perhaps it caught his eye for the sitter’s unusual profil perdu pose: she is shown from behind rather than from the front, with her head gracefully turned to the side.

This early purchase demonstrates Clowes’s abiding and lifelong interest in portraiture. Writing to the connoisseur and art dealer Pierre Nesi, Clowes remarked on his special fondness for the genre:

Incidentally, I am beginning to feel that Corneille de Lyon is on the whole preferable to Clouet, particularly as the works of the latter tend to be somewhat nebulous. As you know, I have a weakness for fine, small portraits and for this reason am greatly interested in the possibilities offered by the French school, particularly now that there have been such upheavals in Europe, provided one can be sure of a sound title to anything that is brought from Europe at the present time and for some years to come.17

In due course, Clowes added many “fine, small portraits” to his collection, including notable works by Corneille de Lyon, Clouet, and Rembrandt.

This initial burst of collecting activity was also facilitated by Clowes’s purchase in 1933 of a spacious Tudor-style home in the Golden Hill neighborhood of Indianapolis, which the family named Westerley (fig. 4).18 Throughout his life, Clowes enjoyed arranging works from his collection to their greatest advantage throughout the house. In “public” spaces, such as the stairwell, dining room, and drawing room, he mainly displayed Italian and Spanish religious works and large portraits, including another Reynolds portrait that he acquired in 1935 and hung above the dining room fireplace. For his study, however, Clowes preferred small-scale, intimate portraits. Discussing the purchase of a delicate female portrait attributed to Corneille de Lyon, for example, Clowes remarked, “Ever since I first saw it I have wanted it for my collection, to include in my library with the self portraits of Hals and Holbein and one or two more very fine small pictures."19 His desire to acquire a similar-sized male portrait by Corneille to hang as a pendant (which he did six months later) demonstrates his often systematic approach to collecting.20

In addition to finely painted portraits, intimate self-portraits seem to have held a particular fascination for Clowes, who gave these pictures prominent positions among the bookshelves of his personal library (fig. 5). He added several prominent examples to his collection over the years. Among these is a jauntily painted depiction of Frans Hals, formerly in the royal collections in Dresden, and a round portrait of Hans Holbein measuring just over 4 inches in diameter, which he bought three years later, in 1937.21

Clowes’s immense ambitions as a collector are perhaps best demonstrated by a group of early portrait purchases from the New York dealer Abris Silberman (1896–1968), a partnership that bookended his quarter-century-long collecting career. No stranger to bold scientific gambles, Clowes was unafraid of making audacious acquisitions practically from the start, buying works by some of the most famous Old Masters from Italy and Northern Europe. In 1935, he paid Silberman no less than $45,000—a princely sum in the depths of the Depression—for a portrait he believed was painted by Albrecht Dürer (now attributed to Hans Schäufelein the Elder, one of Dürer’s assistants; fig. 6).22 The portrait occupied a prominent position in Clowes’s study, and apparently a special place in his heart: two decades later, when commissioning his own portrait, he pointedly chose to be depicted with this painting in the background (fig. 7).23

Abris Silberman was ever attentive to the desires and demands of his client, in whom he saw huge potential. He was also unstinting in his flattery. “Your collection is an example of one well chosen, with intelligence, and at the same time, as the finest investment,” he wrote to Clowes in December 1935. “I am certain that yours is going to be, in the not so distant future, the finest and best in this country…. Any scholar or art historian who comes to this country will not be able to avoid going to view your collection."24 While it is difficult to judge from Clowes’s rather formal letters what effect such effusive praise had, it undoubtedly gave him confidence and encouraged his entrée into a world he knew little about.

Outwardly, Clowes appears to have struck his contemporaries as a self-assured collector. His collection was widely hailed as exceptional, and he was generally praised for his connoisseurship—though not always unreservedly. In a letter to Silberman, Tarkington archly recounted:

[W]hen we went to Dr. Cloues’s [sic] house … and … looked over his pictures, we were very enthusiastic about everything except the Reynolds, which I don’t think he had from you, but from Zinken [sic]. We were non-committal about that….25

Whatever his talents as a connoisseur, Clowes’s scientific background gave him a solid understanding of the relatively new field of technical analysis, a distinct advantage over other serious collectors of his day.26 He would carefully examine the surface of a potential purchase in direct sunlight, looking for clues as to its true condition. And he frequently supplemented this scrutiny with sophisticated analytical techniques such as X-radiography, infrared spectroscopy, and examination under ultraviolet light. When a work’s appearance raised questions as to its condition or attribution, technical results were occasionally the deciding factor.27 Nor did Clowes hesitate to ameliorate the condition of a painting he liked; if it appeared dirty, abraded, or clouded, he enlisted the services of several trusted “restorers” to address the issue, who often employed more aggressive methods than might be attempted today.28

Privately, however, Clowes relied heavily on the expertise and judgment of others. Chief among them was his wife, Edith, who had taken courses in art history at Vassar and frequently served as a sounding board for questions of acquisition or display.29 On one occasion, the couple spent hours arranging photographs of 12 newly purchased altarpiece panels, in search of the best configuration.30 And while Clowes never retained the services of a professional advisor, he turned to an ever-widening circle of art world figures when weighing a purchase, including dealers, scholars, museum professionals, and other collectors. His correspondence is peppered with scholarly opinions on one painting or another. Like a museum curator, he compiled meticulous “dossiers” for each object in his collection, which he enthusiastically made available to art historians around the globe. Their contents generally included photographic reproductions, relevant publications, correspondence, and “expertises,” or letters of authentication, which Clowes solicited from such renowned scholars as Wilhelm Valentiner, Erwin Panofsky, and William Suida.31

Whether Clowes’s scrupulous research compensated for an innate lack of confidence or sophistication is impossible to say. Nevertheless, in his zealous attention to the minutest details of a work and his occasionally pettifogging demands to dealers, one senses that Clowes attempted to apply the precision and empiricism of scientific inquiry to the more intuitive realm of the connoisseur. Perhaps it was his relative lack of sophistication in this regard that drew the subtle condescension of Tarkington:

I’m sure all of you will agree with all of us that even Dr. Clowes, studious as he is, could not outdo [the art dealer] Mr. Edwards … in certain particulars. In fact, we rather feel that Dr. Clowes comparatively seem[s] to wear a kind of pallor.32

Regardless of his merits as a connoisseur (or his peers' view of them), Clowes was a generous and prolific lender of works from his collection, acceding to requests for exhibitions large and small in North America and Europe. He also placed great importance on having his works published. To facilitate this, he kept multiple photographs at hand, ready to dispatch them on request. Indeed, having the work reproduced in an exhibition catalogue was often a condition for lending it:

I shall be very glad to have the accompanying photograph used for reproduction, but I do want to have it clearly understood that my picture … will be reproduced in some form or another in a bulletin or catalogue and that you will send me two or three copies for the record…I have for some time made it a rule that I do not loan any pictures from my collection unless they are going to be reproduced in the catalogue or some equivalent publication….33

Clowes’s motives were not entirely selfless, of course. As works in his collection were exhibited and disseminated in print, their value increased, along with his own stature and renown as a serious collector. In later years, he was somewhat of a victim of his own success in this regard: as requests to borrow his works multiplied, he found himself increasingly deprived of his own collection. “I think you will understand,” he responded to one such request, “that my family and I would naturally prefer to keep [the paintings] in our own home and if we agreed to send them to all the exhibitions which would like to have them at the present time we should practically never see them ourselves."34

Clowes unquestionably enjoyed spending time with his collection. His son George recalled fondly how much happiness his father derived from having his pictures with him at Westerley. A chronic insomniac, Clowes would often retire to his bedroom with a new acquisition in tow, studying it deep into the night.35 He took special pleasure in arranging and rearranging paintings around the house. His letters frequently envision new groupings of works, necessitated by the gaps created by outgoing loans.36 Clowes was also passionate—even a bit obsessive—about the display of works in his collection. His letters are full of questions and observations about proper framing, lighting, and design practices. These range from discussions about the right frame styles and colors to the intensity of the light bulbs that illuminated his paintings.37 Not surprisingly, he insisted on personally overseeing any adjustments.

In forming and shaping his collection, Clowes was undoubtedly influenced by his involvement with the John Herron Art Institute (forerunner to the Indianapolis Museum of Art), whose board of directors he joined in 1934. Almost immediately, he was invited to join the Fine Arts Committee, charged with approving or denying proposed acquisitions on behalf of the institution. In this capacity, Clowes rubbed elbows with other avid art collectors, including Carolyn Marmon Fesler (1878–1960) and Tarkington. Discussions were lively and occasionally contentious, with members championing divergent collecting priorities: Fesler’s appreciation of modern artistic trends occasionally ran afoul of Tarkington’s exclusive taste for the Old Masters.38

As Clowes’s ties to the Herron Art Institute grew over the years, he became a generous benefactor, making gifts of art and regularly underwriting the costs of exhibitions and the accompanying catalogues—many of which included works from his own collection.39 Apart from the aesthetic enjoyment they provided, he was of the view that these shows were a boon to the city and to society as a whole:

These exhibitions which deal with a field never adequately covered in this country in the past draw visitors from all over the country, who often are stopping off in Indianapolis for the first time and paying their first visit to our art institute. They also, of course, draw big crowds from Indianapolis and the vicinity and their educational and cultural value, particularly for school children and students, is incalculable. I am absolutely convinced—and I am sure you will agree with me—that good music, good pictures, and good theaters are just as important as good libraries in exerting a stabilizing and civilizing influence on large numbers of people and tending, at least to some extent, to overcome the sheerly materialistic attitude which is unfortunately so widespread in this country at the present time.40

In a fitting tribute, the Herron Art Institute acknowledged Clowes’s considerable largesse with a memorial exhibition of works from his collection in 1959.41

Clowes’s retirement from Eli Lilly and Company in 1946 allowed him to devote more attention to art collecting and other leisure activities. He ventured beyond his relationship with Silberman Galleries and began to purchase works from other dealers, though sometimes with unsatisfactory results. On occasion he found that he had been taken advantage of and was forced to enter into lengthy negotiations and even legal measures to rectify the situation. “Frankly, I am through with the type of dealer whose primary objective is to sell a picture for the largest sum that he can obtain,” Clowes complained, “regardless of the effect that following such a course may have on his future relations with his client. I am also through with the type of dealer who, when he has once sold a picture, loses all interest in it…."42 Casting his net in a new direction, Clowes turned to Bertram Newhouse and his son Clyde, the proprietors of Newhouse Galleries in New York. Thus began the most fruitful partnership of Clowes’s collecting career. In the dozen years that followed, he obtained from them many of the greatest treasures in his collection.

Among the first of these important acquisitions was an exceptional early self-portrait by Rembrandt, now one of the Collection’s most celebrated works (fig. 8). Painted in about 1629, it captures the ambitious young artist’s features with remarkable honesty, from his partially opened mouth and scruffy chin down to the odd pimple or two. Clowes was immediately intrigued and roused to action by Bert Newhouse’s warning that "there may well not be another Rembrandt Self Portrait for sale during our lifetime."43 On inspecting the work in Indianapolis, Clowes soon envisioned a prized place for it in his collection:

There is no doubt that the Rembrandt self portrait grows on one the more one looks at it. There can be no doubt that it is the work of the great artist, even though he was very young at the time…. I do hope to build up a very substantial dossier around it, especially as I am now considering taking steps to make our collection permanent and undoubtedly the Rembrandt self portrait would be one of the two or three most important pictures in the collection.44

Clowes followed up this purchase with several others over the next five years, all from Newhouse Galleries. These included the Sleeping Cupid, now attributed to a follower of Caravaggio; three half-length depictions of apostles by El Greco and his workshop; and a masterful Rubens oil sketch from about 1621, the Triumphant Entry of Constantine into Rome. Clowes was especially proud of the Rubens, writing to Clyde Newhouse:

I cannot tell you how much we appreciate this Rubens sketch and how glad we are that your father could arrange to let us have it. It cost us more than anything else in our collection, but I think that we also esteem it more highly than anything else, even the Grecos.45

Clowes by this point was no stranger to Spanish art, having already purchased several paintings over the past two decades. Now, he glimpsed new opportunities to acquire important works at reasonable prices:

As I see the situation, the owners of pictures in Spain are still far less sophisticated than are the great owners of private collections in Europe, [who]…under the influence of [Joseph] Duveen, have already made sales at very high figures and are well aware of the present and possible future values of their pictures.46

Clowes saw the greatest potential in El Greco, whose works had “probably not reached anything like full recognition as compared with lesser impressionistic artists in the later period, like Cezanne, Van Gogh, etc.” He promptly acquired the three El Greco apostolados, from a set of twelve that originally adorned the parish church of Almadrones in the Spanish province of Guadalajara, and proudly hung them in the central hall at Westerley (fig. 9).

Clowes’s shrewd appraisal of the market for Spanish art reflects his enterprising approach to scientific endeavors and art collecting alike. In some cases, he purchased works with the intention of selling them at a profit. In 1956, Clowes purchased El Greco’s St. James the Greater from Newhouse Galleries for $75,000 (fig. 10).47 Even as he contemplated the purchase, however, he wrote to Clyde Newhouse to inquire about the prospects of selling it:

I should also like to know whether, if I decide to sell the El Greco at some time in the next six months to a year, what price I could expect to get for it. I remember that you or your father told me that somebody would be glad to pay $100,000 for it and if I remember rightly your father said that the best prospect of getting a really big price for it would be to sell it to one of the Greeks, who owns large numbers of tankers.48

Clowes occasionally partnered with others on such ventures. In 1952, he and an Indianapolis attorney named Elijah B. Martindale purchased 19 medieval frescoes from the Hermitage of San Baudelio de Berlanga, designated a Spanish national monument in 1917. For several years, Clowes and Martindale attempted to sell them to various art museums across the country, with mixed success. A deal with the Prado to exchange the entire group of frescoes for two works by Diego Velázquez fell through, but six were eventually bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.49 Clowes and Martindale donated another two to the Herron Art Institute in 1957.50

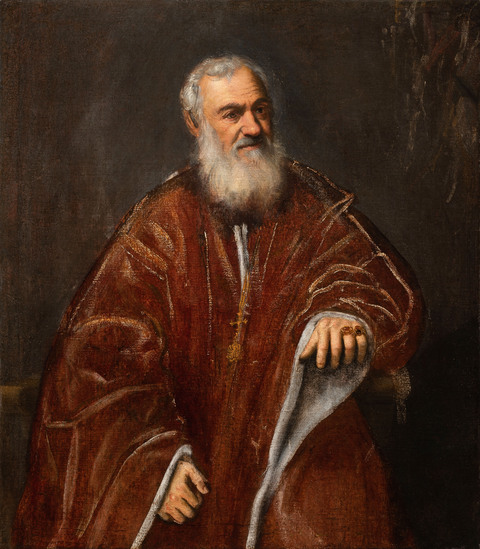

In the fall of 1951, Clowes received a breathless report from Bert Newhouse, who hinted that he might be able to obtain “five great pictures from Liechtenstein."51 These paintings were owned by one of the greatest art collecting dynasties in all of Europe: the Princely House of Liechtenstein. From this group came another cornerstone of the Clowes Collection, Jusepe de Ribera’s depiction of an ancient scholar, now thought to be the Greek mathematician Euclid (fig. 11). One of a series of six imaginary portraits of ancient philosophers, the painting was commissioned from Ribera in 1636 by Prince Karl Eusebius von Liechtenstein and had been in the family’s possession ever since.

While significant acquisitions such as this one have come to define the collection in many ways, a more complete picture of Clowes’s personal preferences and taste in art is conveyed by the works that he decided not to purchase, and those he later sold from his collection. Well aware of Clowes’s resources and interests, flocks of dealers beat a path to his door to present objects for his consideration. Not all were welcome; as Tarkington noted, Clowes could be a mercurial patron:

Mr. Vose writes me a little unamiably that he can’t do business with Dr. Clowes; finds him a very difficult client—so much so that he gives up, [and] relinquishes all claims to him. Last winter Dr. C[lowes] was very much upset because Mr. V[ose] had sent him a [George] Romney without permission.52

Naturally, Clowes was forced to turn away many more works than he could afford to buy. In some cases, he felt that his collection was already well represented in a particular area. In response to the offer of a John Constable landscape, for example, Clowes demurred, noting, “I already have in my collection everything I wish of that type."53 Other opportunities came via two Russian dealers, Count Ivan N. Podgoursky (1901–1962) and Jacob M. Heimann (1881–1960). While Clowes acquired several important works from both, he was eventually forced to bring a lawsuit against Heimann for deliberately misrepresenting the value of a painting.54 Seeking to resolve the matter, Heimann offered up Tintoretto’s Portrait of Tommaso Rangone in partial exchange for three other paintings (fig. 12).55 Clowes rejected this offer, however. And in 1958, just months before his death, the New York dealer Nicholas Acquavella offered Clowes the chance to purchase an original work by Caravaggio, The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist—“the only painting by this master in the art market in the world”—for the sum of $70,000 (fig. 13).56 The high price alone would not have deterred Clowes, as he had purchased the El Greco St. James the Greater for an even higher price two years earlier. He nevertheless declined the offer. It is tempting to speculate how such significant additions might have altered the character and renown of his collection.

Never one to rest or even slow down, Clowes remained quite active in the cultural sphere during his final years. Invigorated by his partnership with Newhouse Galleries, his collecting activity reached new levels. In addition to acquiring new works, he sold several others from his collection. Among them was his portrait of the Prince of Nassau by Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun to Ivan Podgoursky, who then sold it to Grace Showalter back in Indianapolis. (She ultimately gave the painting to the John Herron Art Institute, and it remains part of the IMA’s permanent collection.57) Others he simply gave away, as was the case for a seascape by Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding, which he donated to the Smith College Museum of Art.58

Clowes also continued to champion the cause of several local organizations, including the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, for which he planned to erect a hall on the campus of Butler University, and Trinity Episcopal Church, which he and Edith helped to design and construct. He continued his travels to art museums in the United States and abroad, and his involvement with the John Herron Art Institute seems to have increased during this period. Writing to a colleague just after his 80th birthday, Clowes noted:

I have been working hard this summer and do not find that being eighty years old makes very much difference, but I do realize that I must keep going if I want to finish off the various things that I am now doing…[and] in which I am really interested.59

Among the most important of these was planning for the future of his art collection. Having clashed with the Internal Revenue Service over the back payment of income taxes, Clowes was well aware that bequeathing his collection to his heirs outright would result in a huge estate tax bill, for which he would have to sell off some of the more notable paintings in his collection to pay. In a letter to Abris Silberman, Clowes indicated that he might sell the Cranach Crucifixion, the portrait of Frans Hals, and the Neroccio Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist and St. Mary Magdalene.60 Thankfully, a solution was found that would enable the collection to remain at Westerley. Clowes arranged for the legal transfer of the collection to a charitable foundation, The Clowes Fund, which he established in 1952 to support and preserve his art collection in perpetuity.

Six years later, on 25 August 1958, Dr. George H.A. Clowes died at Woods Hole, two days shy of his 81st birthday. He was survived by Edith, his devoted wife of 48 years; his two sons, George, Jr. and Allen; and five grandchildren. As tributes from Clowes’s scientific colleagues poured in, so too did those from fellow art lovers around the world. In a touching letter to Edith, Silberman wrote:

Dr. Clowes did not just buy works of art. He brought together a Collection which reflected his own taste and knowledge and understanding. This is a Collection distinctive too, for the personality of its founder. Although he was a scientist by profession, Dr. Clowes’s appreciation of a work of art was acute and his knowledge equalled that of many art experts.61

There could hardly be higher praise for a man who had devoted his life to the pursuit of excellence in science as well as art.

The Clowes Collection, 1958 to the Present

Like her husband, Edith Clowes was heavily involved in the cultural life of Indianapolis. Known to her friends as “The Duchess,” she was widely respected for her generous philanthropy and her love of art, music, and gardening.62 She was one of nine founders of Orchard Country Day School (now called The Orchard School) and served several terms on the board of the Planned Parenthood Center. With her impeccable manners, elegant coiffure, and Anglophile tastes, she made Westerley a destination for visiting scientists, artists, musicians, and intellectuals. She was also quite proud of the art collection and relished showing it to her invited guests and the public.63

In order to keep the collection intact at Westerley, Edith initially opened her home to visitors one day a week, by appointment. A guide to the collection was typed up and made available to visitors, and Ian Fraser, future curator of the Clowes Collection at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, was hired as a part-time tour guide. With limited hours and a lack of publicity, very few visitors came. When the IRS objected to this arrangement, Edith was forced to make the collection more accessible; she welcomed the public to Westerley two days a week for four hours and ran advertisements on the radio.64

Together with her son Allen, who resided with her at Westerley, she took an active role in growing and shaping the collection after her husband’s death. The highest quality objects that they purchased were eventually transferred to the Clowes Fund and are now credited as part of The Clowes Collection. Many other objects, mainly minor works, remained in their personal possession. Nearly all were purchased from art dealers with whom Dr. Clowes had maintained close ties during his lifetime, including Thomas Agnew & Sons in London and Newhouse Galleries in New York.

Among Edith and Allen’s most important acquisitions were Jan Brueghel the Elder’s River Landscape, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Younger’s Flowers in a Glass Vase, and Claude Lorrain’s Rest on the Flight to Egypt, all purchased in 1959, within a year of Dr. Clowes’s death. Indeed, Edith loved the Bosschaert still life so much that she later had it included in the background of her own portrait, which she commissioned as a pendant to that of her late husband. The year 1963 saw another burst of painting purchases, including a self-portrait attributed to Anthony Van Dyck, Hans Baldung’s Portrait of a Man in Front of a Rose Hedge, and a delicate depiction of a Franciscan saint attributed to a follower of Hans Memling—all from Newhouse Galleries.65 In 1966, Edith bought an exquisite still life from 1623 by the Spanish painter Juan van der Hamen, though she later sold it back to Newhouse Galleries.66 A similar situation arose with Edith’s purchase of J.M.W. Turner’s remarkable painting Glaucus and Scylla for $125,000; she later returned the work to Newhouse for unknown reasons, and it was purchased by the Kimbell Art Museum the following year.67 Minor acquisitions made by Edith during the same period include Hubert Robert’s Statue Amid Ruins (2015.31) and a small triptych formerly attributed to Domenico Beccafumi.

Like Clowes, Edith and Allen also sold numerous works from the collection. They include

the El Greco painting of St. James the Greater, discussed above, which Clowes had purchased at great expense from Newhouse Galleries in 1956. This particular decision was more practical than aesthetic, however, as the funds were needed to support the construction of Clowes Memorial Hall at Butler University.68 Other notable works sold after Clowes’s death include a small tondo depicting St. Benedict in profile, attributed to Sano di Pietro; View of the Grand Canal with Sta. Maria della Salute, attributed to Canaletto; and a portrait of a young lady attributed to Goya.69 Edith also donated works of art to local organizations, as was the case with a landscape by Thomas Barker of Bath, which she gave to Harry E. Wood High School in 1966.

These later sales and acquisitions did not fundamentally alter the gestalt of the collection that Clowes had built, however. The works that Edith and Allen added to the collection after Clowes’s death were straightforward representatives of the French, German, Flemish, and English schools, thus continuing the general trajectory Clowes had established through his own acquisitions. This was the case with one of Edith’s first acquisitions, Brueghel the Elder’s River Landscape, which Clowes had seen just months before his death.70 Whether he would have made exactly the same choices is perhaps less significant than the degree to which those later additions have come to be identified with—and representative of—the collection as a whole. Their inclusion as part of the Clowes Collection slightly but inevitably distorts our understanding of Clowes’s particular collecting vision and approach.

Though Edith and her sons shared a desire to keep the collection intact at Westerley, it soon became apparent that a sizeable fund would be required to maintain the property and safeguard the collection. George Jr. believed that this was beyond the family’s financial capacity, however. They began discussions with representatives from the John Herron Art Institute, who felt that the collection would better serve the community in the context of the museum’s permanent collection. The timing of these negotiations was fortuitous, as discussions were already under way for the construction of a new campus at the intersection of 38th Street and Michigan Road. Edith, George, and Allen eventually agreed to a long-term loan of the collection to the newly renamed Indianapolis Museum of Art, with the goal of eventually transferring its ownership to the institution. In 2000, The Clowes Fund began to formally transfer ownership of the collection to the IMA, with the accession of the final portion of the collection anticipated in late 2022.

Following Edith’s death in 1967, the brothers agreed to fund the construction of a separate building to house the collection, which was moved from Westerley in 1971. Forerunner to The Robert Lehman Wing at the Metropolitan Museum, which opened to the public in 1975, the Clowes Pavilion was named in Edith’s honor rather than her husband’s. It opened to the public on 8 April 1972. Following a four-year renovation and reinstallation beginning in 2018, the Clowes Pavilion reopened to the public once again in March 2022, almost exactly fifty years after its inauguration. The priceless collection it houses represents a compelling portrait of the remarkable family that created it.

Notes

-

This figure excludes separate gifts and bequests from Dr. Clowes and various members of the Clowes family, which number more than 400 additional objects, including four illuminated manuscripts, furniture, and works of decorative art. ↩︎

-

Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (John Herron Art Museum, 1959); A Lenten Exhibition: Loaned by the Clowes Fund, Incorporated of Indianapolis, March 11 to April 8, 1962, exh. cat. (Notre Dame: Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, 1962); Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, exh. cat. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Museum of Art, 1963); Italian, Flemish and English Paintings, 1500–1800: From the Clowes Fund Collection Exhibition, Franklin College, May 2–16, 1965, exh. cat. (Franklin, IN: Franklin College, 1965); and A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973). ↩︎

-

These documents include personal letters, official correspondence, personal memorabilia, photographs, and objects in the Collection. Since the year 2000, The Clowes Fund has gradually transferred ownership of the Clowes Collection to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, with 2022 marking the final and complete transfer. ↩︎

-

George Henry Alexander Clowes (hereafter referenced as GHAC), Research report to Eli Lilly and Company’s management, 1920. Cited in George H.A. Clowes, Jr., “George Henry Alexander Clowes, PhD, DSc, LLD (1877–1958): A Man of Science for All Seasons,” Journal of Surgical Oncology 18 (1981): 206. ↩︎

-

R.C. Buley, “A History of Eli Lilly and Company” (unpublished typed manuscript, Lilly Archives, Lilly Center, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, 1967), 164. Quoted in James H. Madison, Eli Lilly: A Life, 1885–1977 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1989), 55. ↩︎

-

“About Roswell Park: History, 1898–1950,” https://www.roswellpark.org/about-us/history/1898-1950 (accessed February 7, 2022). ↩︎

-

Clowes’s contributions to this field were recognized in 1961, with the establishment of the G.H.A. Clowes Award for Outstanding Basic Cancer Research, awarded annually by The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). ↩︎

-

GHAC, Banting Memorial Address, delivered to the American Diabetes Association, Atlantic City, 7 June 1947, published in Proceedings of the American Diabetes Association 7, no. 1 (1948): 60. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Dr. G.W. McCoy, October 1919. Quoted in George H.A. Clowes, Jr., “George Henry Alexander Clowes, PhD, DSc, LLD (1877–1958): A Man of Science for All Seasons,” Journal of Surgical Oncology 18 (1981): 205. ↩︎

-

Letter from J.K. Lilly, Sr. to Eli Lilly and J.K. Lilly, Jr., 30 January 1920, Eli Lilly and Company Archives vault, Lilly Center, Indianapolis. Quoted in James H. Madison, Eli Lilly: A Life, 1885–1977 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1989), 55. ↩︎

-

GHAC, Banting Memorial Address, delivered to the American Diabetes Association, Atlantic City, 7 June 1947, published in Proceedings of the American Diabetes Association 7, no. 1 (1948): 53. ↩︎

-

GHAC, Report to Eli Lilly and Company’s management, October 1920. Cited in Alexander W. Clowes, The Doc and the Duchess: The Life and Legacy of George H.A. Clowes (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016), 69. ↩︎

-

With typical deference, Clowes credited the development of the isoelectric process to George Walden, a member of his staff at Eli Lilly and Company. GHAC, Banting Memorial Address, delivered to the American Diabetes Association, Atlantic City, 7 June 1947, published in Proceedings of the American Diabetes Association 7, no. 1 (1948): 54. ↩︎

-

The invoices for these purchases, dated 1 April, 7 May (or 5 July?), 9 May, and 13 May 1930, are preserved in the Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

These comprise a missal for Dominican use (TR10965/1), a Flemish book of hours TR10965/2, an hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary (TR10965/3), and an hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary for use of Rome (TR10965/4). ↩︎

-

A bill of sale bearing this date and signed by Arthur Zinkin is preserved in the Clowes Registration Archive (C10038), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

GHAC to Pierre Nesi, 6 January 1947, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. I am grateful to my colleague Annette Schlagenhauff for bringing this letter to my attention. ↩︎

-

The family’s summer home in Woods Hole was duly christened Easterly. ↩︎

-

GHAC to Pierre Nesi, 6 January 1947, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. The Corneille de Lyon work is the Portrait of Marie de Guise, now workshop of the artist (The Clowes Collection, 2017.88. ↩︎

-

“Incidentally, I hope … to acquire a good portrait of a man by Corneille de Lyon corresponding approximately in size with the little portrait you now have. Do you know by any chance of any possible male portrait that would make a good pair with the one you now have?” GHAC to Pierre Nesi, 6 January 1947, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. In July of the same year, Clowes purchased from Nesi the Portrait of a Man, possibly René du Puy du Fou by Corneille de Lyon (The Clowes Collection, 2014.86). The bill of sale, dated 26 July 1947, is preserved in the Clowes Registration Archive (C10028), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Both works—the Portrait of Frans Hals (The Clowes Collection, 2015.28) and the Portrait of Hans Holbein (The Clowes Collection, 2014.90)—have since been deattributed and are now generally regarded as copies after original self-portraits. ↩︎

-

The sale contract, signed and dated 18 April 1935, refers to the work as an authentic painting by Albrecht Dürer. Clowes Registration Archive (C10032), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Apparently, Clowes regarded the “A” embroidered on the man’s shirt to be a variant of Dürer’s famous “AD” monogram, though this does not seem to be corroborated by any extant archival documents. ↩︎

-

It is worth noting that the portrait was thought by William Suida to depict the prominent German jurist, diplomat, and humanist Dr. Christoph (von) Scheurl (1481–1542), which may have added to its appeal to Clowes. ↩︎

-

Letter from Abris Silberman to GHAC, 20 December 1935, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Booth Tarkington to Abris Silberman dated 15 March 1934, IHS B. Tarkington Materials, Indianapolis Museum of Art Archives at Newfields. ↩︎

-

For a more in-depth discussion of Clowes’s interest in technical analysis and painting conservation, see the accompanying essay by Roxy Sperber in this catalogue. ↩︎

-

“Benny arrived with the Van Dyke [sic], which is truly a noble work, but when I examined it in strong sunlight I felt that its condition was not too good…and since your father had actually already sold it and wanted to have it back by Monday, which precluded the possibility of studying it with x-rays, infrared, ultraviolet, etc., I decided to let it go….” Letter from GHAC to Clyde Newhouse, 6 December 1951, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Among the pioneers in the field hired by Clowes were the restorers Ludwig Furst, William Suhr, Anthony Riportella, and Edward O. Korany. ↩︎

-

“I have no prejudices whatever and if you can offer me something that Mrs. Clowes and I particularly like, or like better than something we now have, you may rest assured that if we are in a position to buy it or to effect an exchange with something we like less, we shall be only too glad to do it.” Letter from GHAC to Pierre Nesi, 6 January 1947, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

“Mrs. Clowes and I have set out the photographs two separate ways, the first being three sets of four, one above another, the second being two sets of six, one above another.” Letter from GHAC to Bert Newhouse, 5 May 1952, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

A typical example is Panofsky’s letter to GHAC dated 10 November 1942, concerning the El Greco St. Thomas (The Clowes Collection, 2008.276) and the Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, now Bellini and workshop (The Clowes Collection, 2000.341). Clowes Registration Archive (El Greco, St. James, the Greater), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Booth Tarkington to Abris Silberman dated 29 September 1938, IHS B. Tarkington Materials, Indianapolis Museum of Art Archives at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Wolfgang Stechow, 17 January 1957, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Mahonri Sharp Young, 8 June 1954, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

George H.A. Clowes, Jr., “George Henry Alexander Clowes, PhD, DSc, LLD (1877–1958): A Man of Science for All Seasons,” Journal of Surgical Oncology 18 (1981): 211. ↩︎

-

A typical example is found in a letter from GHAC to Clyde Newhouse, 16 November 1951: “We feel that the Rubens would be shown to far greater advantage, now that it is grouped with the Hals and the Rembrandt, if it had a black frame similar to that of the Hals…we propose to group the Hals, Rembrandt, and Rubens at one corner of the room…. When the little Corneille de Lyon of Diane de Poitiers is returned from Pittsburgh, we shall place it where the little El Greco has been up to the present time, either moving the El Greco to a position on the righthand side of the fireplace, over which we have a Titian, or into the little reception room, in which the Spanish pictures are now placed.” Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

The lighting apparatus for the Rembrandt Self-Portrait (C10063) was the subject of numerous letters to Bert Newhouse, for example: “When we put the Rembrandt on the stand…we found that the heat from the lights which you had installed was too great, so for the present we put in two of the oldfashioned [sic], standard lights, which generate less heat. We could have used the new lights but for the fact that the lighting fixture…was screwed to the back of the frame in such a way that it was not possible to move the light upward and outward….This is a matter about which I have always been greatly concerned. I have seen serious damage done to valuable documents by exposure to too hot a light and am always uneasy about a picture, especially if it is on a wooden panel.” Letter from GHAC to Bert Newhouse, 22 May 1951, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Tarkington ultimately led the Fine Arts Committee to reject Fesler’s proposal for the museum to acquire Picasso’s Ma Jolie (61.36) and a Braque’s Still Life with Pink Fish (61.39). Thankfully, both paintings were acquired by Fesler herself, who hung them in her living room and eventually bequeathed them to the IMA. Tarkington subsequently penned a humorous bit of doggerel, perhaps by way of explanation: “I would not eat a cockeyed fish, / I wouldn’t even try one; / But a cockeyed fish, on a purple dish, / I’d rather eat than buy one.” Quoted in Anne P. Robinson and S.L. Berry, Every Way Possible: 125 Years of the Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2008), 118. A copy of the note is preserved in the Clowes Registration Archive (61.36), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Several works in the IMA’s collection were gifts from Dr. and Mrs. Clowes but are not technically considered part of The Clowes Collection, as they were donated prior to the formation of the Clowes Fund in 1952. These include Benjamin Barker II’s Pony Cart Crossing a Woodland Brook (42.6) and two detached frescoes from the Hermitage of San Baudelio de Berlanga, Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (57.151) and Wedding at Cana (58.23). ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Elsie Sweeney, 10 November 1953, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Clowes was principally involved in the planning of four exhibitions at the John Herron Art Institute, to which he loaned numerous works from his collection: Holbein and His Contemporaries (1950), Pontormo to Greco (1954), Turner in America (1955), and The Young Rembrandt and His Times (1958). ↩︎

-

Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition (John Herron Art Museum, 1959). ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Bert Newhouse, 10 November 1952, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Bert Newhouse to GHAC, 17 May 1951, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Bert Newhouse, 22 May 1951, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Clyde Newhouse, 25 July 1956, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. In his introduction to the 1959 Clowes memorial exhibition catalogue, Kurt Pantzer noted how he “will always remember the intense satisfaction Doctor and Mrs. Clowes expressed at the acquisition of the oil sketch on panel by Rubens portraying the Triumphant Entry of Constantine into Rome….They considered this the most beautiful painting in their collection.” The work occupied a position of prominence along the main stairwell at Westerley. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Bert Newhouse, 10 November 1952, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

The bill of sale from Newhouse, dated 16 October 1957, is preserved in the Clowes Registration Archive (El Greco, St. James, the Greater), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Clyde Newhouse, 13 July 1957, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Edith Clowes sold the painting in 1960 to Knoedler & Co., from which it was bought by David and Peggy Rockefeller. It was sold again at Christie’s New York on 30 October 2018, lot 41. See letter from Clyde Newhouse to GHAC, 15 October 1956, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

The six frescoes acquired by the Met were subsequently exchanged with the Prado for a long-term loan of the twelfth-century apse of the Church of San Martín at Fuentidueña, which is still on view at The Cloisters. ↩︎

-

The two frescoes are the Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (57.151) and the Marriage at Cana (58.23); both are mounted on canvas. Cf. Letter from GHAC to Bert Newhouse, 19 December 1957, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Bert Newhouse to GHAC, 5 September 1951, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Booth Tarkington, letter dated 25 June 1936 (unknown recipient), IHS B. Tarkington Materials, Indianapolis Museum of Art Archives at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Giovanni Castano, 12 March 1958, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

The lawsuit, which dragged on from 1947 to 1949, alleged that Heimann had deliberately misrepresented the value of a female portrait by Bellini that Clowes had purchased from him. After convincing Clowes that the painting was not worth the price he had paid, Clowes returned the painting for a refund, after which Heimann then resold it to another collector at a considerable markup. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Gerald O’Neill, 12 April 1948, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. The final settlement did not involve the Tintoretto, which Heimann subsequently sold to Anne R. and Amy Putnam of San Diego, who gave it to the San Diego Fine Arts Gallery in 1950. It was deaccessioned by the San Diego Museum of Art and sold at Sotheby’s New York on 11 June 2020, lot 1. ↩︎

-

Letter from Nicholas Acquavella to GHAC, 18 January 1958, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. The painting is currently in a private collection and is on long-term loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I am grateful to David Franklin and Sebastian Schutze for their help in identifying this work. ↩︎

-

Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, Portrait of the Prince of Nassau (64.740). ↩︎

-

See the correspondence between GHAC and Robert O. Parks, director of the museum, September 1955–January 1956, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from GHAC to Alex R. Holliday, 1 October 1957, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

“I hope that you will let me know what I can do about any of the pictures in question and any others obtained from you which are not at present hung in our house. We certainly have, among the pictures obtained from you, the Cranach, the Bosch, the Luini, the Neroccio, and possibly the Duccio which would, I feel, be gladly accepted by any of the important museums in the country. I am, of course, trying to work out ways and means of keeping the collection together in the future, after the deaths of Mrs. Clowes and myself, but I am not certain this can be accomplished.” Letter from GHAC to Abris Silberman, 3 January 1957, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Abris Silberman to Edith Clowes, 7 May 1959, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Ian Fraser greatly admired Edith’s generosity and wide-ranging interests and noticed a strength of resolve beneath her genteel surface. Perhaps for this reason, he was always careful to avoid displeasing her. Recalling the meticulous coordination of her Westerley dinner parties, he noted, “It was a rare occasion that failed to have equal numbers of men and women. Equal numbers were invariably invited and, as Mrs. Clowes told us, ‘once you’ve accepted an invitation you show up unless you’re dead.'” A. Ian Fraser, A Sow’s Ear: Digressions and Transgressions of a Gay Humanist (self-pub., CreateSpace, 2013), 150–151. ↩︎

-

“She had an iron fist inside a velvet glove…. She took delight in being wealthy and having this great collection. She was known as ‘The Duchess.'” Ian Fraser, interview with S.L. Berry, February 14, 2007. Quoted in Anne P. Robinson and S.L. Berry, Every Way Possible: 125 Years of the Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2008), 237. ↩︎

-

A. Ian Fraser, A Sow’s Ear: Digressions and Transgressions of a Gay Humanist (self-pub., CreateSpace, 2013), 136–137. A copy of the visitors’ guide, circa 1961 (“Visitors Guide to the Paintings, Objects of Art, and Furniture Collected by Dr. George H.A. Clowes [1877–1958] and Mrs. Clowes”) is preserved in the Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Somewhat confusingly, the Balding and Memling paintings (among others) were never transferred to the Clowes Fund and were given directly to the IMA by Allen. For this reason, they are not technically considered part of The Clowes Collection. ↩︎

-

The Van der Hamen still life, signed and dated 1623, is reproduced in Ingvar Bergstrōm, “Juan van der Hamen y León,” L’Oeil 108 (1963): 29, fig. 8. See also Mark Roskill’s unpublished entry on the painting, 107. ↩︎

-

The painting is listed on a bill of sale from Newhouse Galleries dated 15 October 1965, along with a Madonna and Child by Jan Provost, which also left the collection. Clowes Registration Archive (Jan Provost, “Madonna and Child in a Landscape”), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

“I quite realize that you are anxious to obtain the maximum price for the picture in order to raise money for the Clowes Memorial Hall….” Letter from Edith Clowes to Evelyn Joll (of Thomas Agnew & Sons), 28 April 1960, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. See the letter from Allen Clowes to Evelyn Joll, 25 May 1960: “…the picture has now been sold in New York at a very satisfactory price.” The painting was sold to Newhouse Galleries on 6 May 1960 for $115,000. ↩︎

-

The Sano di Pietro and Canaletto paintings were exhibited at the 1959 Clowes memorial exhibition (cat. nos. 12 and 44); both were sold in or after 1965, as they appear in a typewritten appraisal of works in the collection in the Correspondence files (under Thos. Agnew & Sons.), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. A photograph of the Goya portrait is included in a file folder of works no longer in the Clowes Collection in the same archive. Both the Canaletto and the Goya were sold in March 1967. ↩︎

-

“I am very pleased to say we do have the Breughel which we showed to Dr. Clowes when last we saw him and which, as you write, was under discussion with Dr. Clowes in our recent negotiations.” Letter from Clyde Newhouse to Lenora Clark, 17 September 1958, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎