Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

Inscribed at lower right: RHL

Entry

Author

Provenance

Possibly sold at (Pieter Locquet, Amsterdam) on 22 September 1783, no. 325;

Possibly Pieter (Pierre) Yver (1712–1787), Amsterdam.35

Purchased from a Dutch diplomat in Vienna, Austria, about 1840, by the Polish Count Adolf Husarzewski;36

By descent to his son, Count Jozef Husarzewski, and his wife, Karolina, née Princess Jablonowska;

By descent to their daughter, Countess Eleonora Husarzewska (1866-1940), wife of Prince Andrzej Lubomirski (1862–1953), in their castle at Przeworsk (now Poland);37

To their son, Jerzy (George/Georges) Rafal Lubomirski (1887-1978), Geneva;

(Newhouse Galleries, New York, New York) in 1951;38

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1951;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, since 1958, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10063).

Exhibitions

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898, Rembrandt. Schilderijen bijeengebracht ter gelegenheid van de inhuldiging van hare Majesteit Koningin Wilhelmina, no. 9;

Museum de Lakenhal, Leiden, 1906, Fêtes de Rembrandt à Leyde. Catalogue de l’exposition de tableaux et de dessins de Rembrandt et d’autres maîtres de Leyde, du dix-septième siècle, no. 53c;

Ossoliński National Institute, Lvov, 1911, Exposition des maîtres anciens, no. 52;

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Toledo Museum of Art; Art Gallery of Toronto, 1954–1955, Dutch Painting: The Golden Age; An Exhibition of Dutch Pictures of the Seventeenth Century;

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, 1956, Rembrandt and His Pupils, no. 3;

Marion Koogler McNay Art Institute, San Antonio, TX, 1956, Rembrandt van Rijn;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1958, The Young Rembrandt and His Times, no. 2;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 47;

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition Loaned by the Clowes Fund, Incorporated of Indianapolis, no. 39;

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, 1963, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 37;

Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1974, Panorama: Inaugural Exhibition, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Columbus;39

Bunkamura Museum of Art, Tokyo, 1992, Rembrandt: His Teachers and His Pupils, no. 3;

Royal Cabinet of Paintings, Mauritshuis, The Hague, 1999, Rembrandt by Himself, no. 8 (as attributed to Rembrandt);

Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2006, Rembrandt Face to Face;

Cincinnati Art Museum, 2008, Rembrandt: Three Faces of the Master;

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Cleveland Museum of Art; Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2012, Rembrandt in America: Collecting and Connoisseurship, no. 4;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection;

Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston, ON; The Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, AB; The McKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan; The Art Gallery of Hamilton, Hamilton, ON; 2019–2021, Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges, no. 27 (reproduced);

Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, China; Hunan Museum, Changsha, China; Chengdu Museum; 2020–2021, Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting.

References

Abraham Bredius, “Berichten en Mededeelingen. Onbekende Rembrandts in Polen, Galicie en Rusland,” De Nederlandsche Spectator 25 (June 19, 1897): 198;

Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, Beschrijvende Catalogus der Schilderijen van de Rembrandt Tentoonstelling te Amsterdam September–October 1898 (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1898; French ed., 1899), no. 9;

Marcel Nicolle, “L’Exposition Rembrandt à Amsterdam,” La Revue de l’art ancien et moderne 4 (July–December 1898): 424, 426;

Otto Seeck, “Die Rembrandt-Ausstellung in Amsterdam,” Deutsche Runschau 97 (October–December 1898): 436;

Stedelijk Museum, Rembrandt: schilderijen bijeengebracht ter gelegenheid van de inhuldiging van Hare Majesteit Koningin Wilhelmina, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Roeloffzen-Hübner & van Santen, 1898), no. 9;

Victor de Swarte, “Rembrandt (1607–1669): Exposition du ‘Couronnement’ à Amsterdam,” La Nouvelle revue 21, no. 115 (November–December 1898): 481;

Abraham Bredius, “Kritische Bemerkungen zur Amsterdamer Rembrandt-Ausstellung,” Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, N.F. 10 (1898–1899): 167;

Malcolm Bell, Rembrandt van Rijn (London: George Bell & Sons, 1901), 52, 118;

E.W. Moes, Iconographia Batava. Beredeneerde Lijst van Geschilderde en Gebeeldhouwde Portretten van Noord–Nederlanders in vorige eeuwen, vol. 2 (Amsterdam: Frederik Muller & Co., 1905), no. 6693.11;

Wilhelm von Bode and Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, The Complete Works of Rembrandt, vol. 8, trans. Florence Simmonds (Paris: C. Sedelmeyer, 1906), 34–35, 54, no. 546 (reproduced);

Museum de Lakenhal, Leiden, Fêtes de Rembrandt à Leyde. Catalogue de l’exposition de tableaux et de dessins de Rembrandt et d’autres maîtres de Leyde, du dix-septième siècle, exh. cat. (Leiden: P.J. van Breda Vriesman, 1906), no. 53c;

Frederik Schmidt-Degener, “Le Troisième Centenaire de Rembrandt en Hollande,” Gazette des beaux-arts, ser. 6, vol. 36 (October 1906): 276;

Jan Veth, “Rembrandtiana V. L’Exposition en l’honneur de Rembrandt à la Halle du Drap de Leyde,” L’Art Flamand et Hollandais 3, no. 10 (15 October 1906): 88 (reproduced);

Jan Veth, “Rembrandtiana V. De Rembrandt–Hulde Tentoonstelling in de Leidsche Lakenhal,” Onze Kunst 10, no. 5 (July–December 1906): 84 (reproduced);

Adolf Rosenberg, Rembrandt. Des Meisters Gemälde in 643 Abbildungen, ed. W.R. Valentiner, 3rd ed. (Stuttgart and Leipzig: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1909), 29, 550, 567, 586, and 598 (reproduced);

Alfred Von Wurzbach, Niederländisches Künstler-Lexikon, vol. 2 (Vienna and Leipzig: Halm und Goldmann, 1910), 401;

Jerzy Mycielski, “Odczyt Prof. Dra Jerzego Mycielskiego wygloszony dnia 21. lutego 1909 w salach wystawy” [The Lecture of Professor Jerzy Mycielski Delivered on February 21, 1909, in the Exhibition Rooms], in Album de l’exposition des maîtres anciens, avec cinquante reproductions, ed. Miecislas Treter (Lvov: Ossoliński National Institute/Gubrynowicz et Fils, 1911), 57;

Leon Pininski, “Przemowienie Leona hr. Pininskiego wygloszone przy otwarciu wystawy dnia 17. lutego 1909 r.” [The Speech by Count Leon Pininski Delivered on the Opening of the Exhibition on February 17, 1909], in Album de l’exposition des maîtres anciens, avec cinquante reproductions, ed. Miecislas Treter (Lvov: Ossoliński National Institute/Gubrynowicz et Fils, 1911), 48;

Theodor von Frimmel, Studien und Skizzen zur Gemäldekunde, vol. 2 (Vienna: Kommissionsverlag Von Gerold & Co., 1916), 90–91;

Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century, Based on the Work of John Smith, vol. 6, trans. Edward G. Hawke (London: Macmillan and Co., 1916), no. 549;

W.R. Valentiner, The Work of Rembrandt Reproduced in 643 Illustrations, Classics in Art series, 3rd ed. (New York: Brentano’s, 1921), 29 (reproduced);

David S. Meldrum, Rembrandt’s Paintings with an Essay on His Life and Work (New York: E.P. Dutton and Company, 1923), 20, no. 91 (reproduced);

Kurt Bauch, Die Kunst des jungen Rembrandt (Heidelberg: Carl Winters Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1933), 209 (reproduced as copy, perhaps by Joudreville);

Abraham Bredius, ed., The Paintings of Rembrandt (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1936; orig. publ. in Dutch and German eds., 1935), 3, 29, no. 3 (reproduced);

Bernice Davidson, “Paintings for Princes and Farmers,” Arts Digest 29 (1 December 1954): 11;

Theodore Rousseau, Jr., Dutch Painting: The Golden Age; An Exhibition of Dutch Pictures of the Seventeenth Century, exh. cat. (Haarlem: J. Enschedé, 1954), x, 60 (reproduced)

Paul L. Grigaut, “Rembrandt and His Pupils in North Carolina,” Art Quarterly 19, no. 4 (Winter 1956): 405–406 (reproduced);

W.R. Valentiner, Rembrandt and His Pupils, exh. cat. (Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Art, 1956), 18 and no. 3 (reproduced);

Michał Walicki, “Rembrandt w Polsce” [Rembrandt in Poland], Biuletyn historii sztuki 18 (1956): 334, 347 (reproduced);

James Britton, “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” San Diego & Point Magazine (May 1958): 45 (reproduced);

David G. Carter, The Young Rembrandt and His Times, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1958), no. 2 ;

E.P. Richardson, “Notes on Special Exhibitions,” Art Quarterly 21, no. 3 (Autumn 1958): 288;

David G. Carter, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), no. 47 (reproduced);

F.W. Bilodeau, “The Clowes Fund Collection at Indianapolis, Indiana,” The Connoisseur 148, no. 595 (August 1961): 6 (reproduced);

John Howett, A Lenten Exhibition Loaned by the Clowes Fund, Incorporated of Indianapolis, exh. cat. (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, 1962), no. 39 (reproduced);

H. van Hall, Portretten van Nederlandse Beeldende Kunstenaars (Amsterdam: Swets en Zeitlinger, 1963), no. 1743.6;

Henry R. Hope, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, exh. cat. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Museum of Art, 1963), no. 37;

Kurt Bauch, Rembrandt Gemälde (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1966), no. 289 (reproduced);

Donald Hoffmann, “Old House Has Master Paintings,” The Kansas City Times (September 14, 1967): 4B;

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

Abraham Bredius, Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings, revised by Horst Gerson, 3rd ed. (London: Phaidon, 1969), no. 3 (reproduced as possibly by Lievens);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), xxxiv–xxxv, 82–83 (reproduced);

Indianapolis Museum of Art, Panorama: Inaugural Exhibition, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Columbus, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1974) (reproduced);

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, 100 Masterpieces of Painting: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 92–96 (reproduced);

Anthony F. Janson, “Rembrandt in the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 8–13 (reproduced);

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, Handbook of European and American Paintings to 1945: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1981), unpaginated (reproduced);

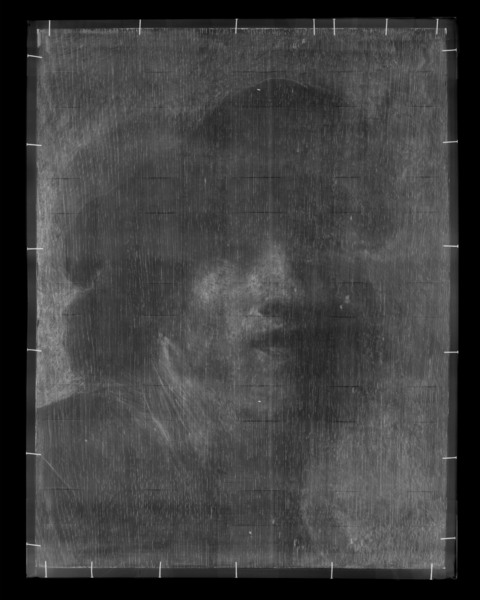

David A. Miller, “Conservation Laboratory Examination Techniques and Conservator’s Report,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 23–28 (reproduced);

Josua Bruyn et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 1, 1625–1631 (The Hague, Boston, and London: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), no. A 22, copy 1 (reproduced as copy);

Christopher Wright, Rembrandt: Self-Portraits (London: Gordon Fraser, 1982), 19, 39, no. 4 (reproduced as disputed identification and attribution);

Werner Sumowski, Gemälde der Rembrandt-Schüler, vol. 3 (Landau/Pfalz: Edition PVA, 1983), under no. 1147 (as higher in quality than Atami version);

Pascal Bonafoux, Rembrandt: Self-Portrait (Geneva: Skira, 1985), 17 (reproduced);

Gary Schwartz, Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings (New York: Viking, 1985; Dutch ed., 1984), 59 (as copy likely produced in studio);

Peter C. Sutton, A Guide to Dutch Art in America (Washington, DC: The Netherlands–American Amity Trust, Inc., 1986), 120 (as possibly not Rembrandt);

Christian Tümpel, Rembrandt: All the Paintings in Colour (Antwerp: Fonds Mercator, 1986), under no. A62 (as perhaps after prototype by Lievens);

Sylvia Hochfield, “Rembrandt: The Unvarnished Truth?” ARTNews 86, no. 10 (December 1987): 106 (reproduced) (as questionable in authorship);

Holliday T. Day, ed., Indianapolis Museum of Art: Collections Handbook (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1988), 24 (reproduced);

Akihiro Ozaki, “MOA bijutsukan shozō no ‘Renburanto no jigazō ni kansuru isshiron – Renburanto aruiwa Dau ka” [A Preliminary Discourse on the “Rembrandt Self-Portrait” in the Collection of the MOA Museum: Rembrandt or Dou?], Bunkakiyou 27 (February 1988): 16–17 (reproduced as contemporary copy);40

Akihiro Ozaki, “A New Look at the Bust of a young man in the MOA Museum,” Art History (Tohoku University, Kawauchi, Japan) 11, no. 3 (1989): 1;

H. Perry Chapman, Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits: A Study in Seventeenth-Century Identity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 146–147, n. 14 (as probably originating in Rembrandt’s studio);

Claus Grimm, Rembrandt selbst. Eine Neubewertung seiner Porträtkunst (Stuttgart and Zurich: Belser Verlag, 1991), 28 (reproduced as possible self-portrait of Dou);

Bunkamura Museum of Art, Tokyo, Rembrandt: His Teachers and His Pupils, exh. cat. (Toyko: Toyko Shimbun, 1992), no. 3 (reproduced);

Anthony F. Janson, “Rembrandt and the Museum: Jan Lievens, Part II,” Previews [North Carolina Museum of Art] (Summer 1992): 12 (reproduced);

Michel van Rijn, “Rembrandt’s Castle,” Art & Antiques (April 1992): 73;

Leonard J. Slatkes, Rembrandt: Catalogo completo dei dipinti (Florence: Cantini, 1992), under no. 237 (as by Jan Lievens);

P.J.J. van Thiel, “De Rembrandt-tentoonstelling van 1898,” Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 40, no. 1 (1992): (reproduced as not by Rembrandt);

Helga Gutbrod, Lievens und Rembrandt. Studien zum Verhältnis ihrer Kunst, Ars Faciendi 6 (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1996), 205–207;

Quinten Buvelot and Christopher White, eds., Rembrandt by Himself, exh. cat. (The Hague: Royal Cabinet of Paintings, Mauritshuis, 1999), no. 8;

Judith Portier-Theisz, Le premier autoportrait de Rembrandt (1628). Etude sur la formation du jeune Rembrandt (Bern: Peter Lang, 1999), 69 (reproduced);

Jørgen Wadum and Caroline van der Elst, “Attribution et désattribution,” Dossier de l’art 61 (October 1999): 41 (as student copy);

The Rembrandt Database, “Self Portrait with gorget and beret, ca. 1629,” https://rkd.nl/explore/images/30168 (as attributed to Rembrandt or after Rembrandt), 6 April 2000, updated 14 December 2021;

Eric Jan Sluijter, “The Tronie of a Young Officer with a Gorget in the Mauritshuis: A Second Version by Rembrandt Himself?” Oud Holland 114, nos. 2/4 (2000): 191;

Jørgen Wadum, “Rembrandt under the Skin: The Mauritshuis Portrait of Rembrandt with Gorget in Retrospect,” Oud Holland 114, nos. 2/4 (2000): 175–176, 184, 185 (reproduced as attributed to Rembrandt);

Ernst van de Wetering, “Delimiting Rembrandt’s Autograph Oeuvre—an Insolvable Problem?” in Ernst van de Wetering and Bernhard Schnackenburg, eds., The Mystery of the Young Rembrandt, exh. cat. (Wolfratshausen: Minerva Hermann Farnung, 2001), 64–65 (reproduced);

Akihiro Ozaki, “Renburanto—Owarinaki chōsen no gaka” [Rembrandt, An Artist Who Never Stops Pushing], Geijutsu Shincho (November 2003): no. 4, ill;

Jeroen Giltaij, Rembrandt Rembrandt, exh. cat. (Frankfurt: Städelsches Kunstinstitut, 2003), 46;

Ben Broos, Ariane van Suchtelen et al. Portraits in the Mauritshuis 1430–1790, ed. Quinten Buvelot (Zwolle: Waanders, 2004), 230–231;

Ellen Wardwell Lee, ed., Indianapolis Museum of Art: Highlights of the Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2005), 97 (reproduced);

Roelof van Straten, Young Rembrandt: The Leiden Years, 1606–1632 (Leiden: Foleor, 2005), 103 (reproduced);

Ernst van de Wetering et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 4, The Self-Portraits (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005), 162, 164, 173, 308, 310, 597, Corrigenda et Addenda no. I A 22, 649 (reproduced);

Stephanie S. Dickey, Rembrandt Face to Face, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2006) (reproduced);

Ernst van de Wetering, “Rembrandt Laughing, c. 1628—A Painting Resurfaces,” Kroniek van het Rembrandthuis (2007): 22, 24;

Dagmar Hirschfelder, Tronie und Porträt in der niederländischen Malerei des 17. Jahrhunderts (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2008), 42, 102, 109, 313, 328, and 330, no. 390, ill;

Benedict Leca, ed., Rembrandt: Three Faces of the Master, exh. cat. (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 2008), 7 (reproduced);

H. Perry Chapman, “Rembrandt, Van Gogh: Rivalry and Emulation,” in Benedict Leca, ed., Rembrandt: Three Faces of the Master, exh. cat. (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 2008), 26–28;

Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt: A Life in 180 Paintings, trans. Murray Pearson (Amsterdam: Local World, 2008), 26 (reproduced);

Dennis P. Weller, Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Paintings: Systematic Catalogue of the Collection of the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh (Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Art, 2009), under no. 26 (reproduced);

H. Perry Chapman, “Reclaiming the Inner Rembrandt: Passion and the Early Self-portraits,” in Stephanie S. Dickey and Herman Roodenburg, eds., The Passions in the Arts of the Early Modern Netherlands, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 60 (Zwolle: Waanders, 2010), 253, 256 (reproduced);

Tom Rassieur, “Rembrandt’s Leiden Years: Mastering His Craft and Defining His Genius,” in George S. Keyes, Tom Rassieur, and Dennis P. Weller, Rembrandt in America: Collecting and Connoisseurship, exh. cat. (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2011) 97, 100–101 (reproduced);

Ernst van de Wetering and Carin van Nes (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 6, Rembrandt’s Paintings Revisited: A Complete Survey (Dordrecht: Springer, 2015), 69, 85, 488–489 (reproduced);

Christopher Brown, “The Evolution of Rembrandt’s Early Style,” in Christopher Brown, An van Camp, and Christiaan Vogelaar, Young Rembrandt, exh. cat. (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2019), 42 (reproduced);

Jacquelyn N. Coutré, ed., Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges, exh. cat. (Kingston, Ontario: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2019), no. 27 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen, et al., Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting (Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing: Nanjing, 2020), 136–138 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen, et al., Floating Lights and Shadows: 500 Years of European Painting (Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing: Nanjing, 2020), 134–137 (reproduced).

Notes

-

Stephanie S. Dickey, Rembrandt Face to Face, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2006), 43. Earlier self-portraits, such as those in Munich (fig. 1) and Amsterdam, are significantly smaller in format. ↩︎

-

The first mention of other versions occurs in 1906, when one was on display at Frederik Muller et Cie in Amsterdam at the same time that the Indianapolis painting was on exhibit in Leiden. See Jan Veth, “Rembrandtiana V. L’Exposition en l’honneur de Rembrandt à la Halle du Drap de Leyde,” L’Art Flamand et Hollandais 3, no. 10 (October 15, 1906): 88; Veth, “Rembrandtiana V. De Rembrandt–Hulde Tentoonstelling in de Leidsche Lakenhal,” Onze Kunst 10, no. 5 (July–December 1906): 84; and Frederik Schmidt-Degener, “Le Troisième Centenaire de Rembrandt en Hollande,” Gazette des beaux-arts, ser. 6, vol. 36 (October 1906): 276. Other than Bredius’s catalogue of 1937, the Clowes painting does not appear in publication between 1933 and 1954. Written communication between respected connoisseurs and Frederick Mont, however, continued to build consensus about the attribution: a letter dated 10 May 1951 from Jakob Rosenberg attests to his belief in the painting’s authenticity post-cleaning, and a note by Edward O. Korany, a restorer who cleaned the painting, of 15 May 1951, confirms the attribution to Rembrandt. Later letters reveal similar endorsements: a letter of 17 September 1957 by Eli Prins endorses the high quality of the painting, and a letter of 12 November 1982 confirms Christopher Wright’s faith in the attribution, as does a letter from Alfred Bader dated 24 November 1986. See File C10063, Registration Historical Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

His recording of an inscription of “1628 (?),” however, was incorrect. See Kurt Bauch, Rembrandt Gemälde (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1966), no. 289. ↩︎

-

Christian Tümpel later voiced his support for the further exploration of this idea. Christian Tümpel, Rembrandt: All the Paintings in Colour (Antwerp: Fonds Mercator, 1986), 430. ↩︎

-

Josua Bruyn et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 1, 1625–1631 (The Hague, Boston, and London: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), no. A22. ↩︎

-

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, 100 Masterpieces of Painting: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 92–96. ↩︎

-

David A. Miller, “Conservation Laboratory Examination Techniques and Conservator’s Report,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 23–33. His comparison of the X-radiographs of the Indianapolis and Atami panels offers the best substantiation of his position. ↩︎

-

Christopher Wright, Rembrandt: Self-Portraits (London: Gordon Fraser, 1982), 19; Gary Schwartz, Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings (New York: Viking, 1985), 59; H. Perry Chapman, Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits: A Study in Seventeenth-Century Identity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 146–147; and Leonard J. Slatkes, Rembrandt: Catalogo completo dei dipinti (Florence: Cantini, 1992), under no. 237. A notable exception is Bunkamura Museum of Art, Tokyo, Rembrandt: His Teachers and his Pupils, exh. cat. (Toyko: Toyko Shimbun, 1992), no. 3. ↩︎

-

Jørgen Wadum, “Rembrandt under the Skin: The Mauritshuis Portrait of Rembrandt with Gorget in Retrospect,” Oud Holland 114, nos. 2/4 (2000): 164; Ernst van de Wetering, “Delimiting Rembrandt’s Autograph Oeuvre—an Insolvable Problem?” in Ernst van de Wetering and Bernhard Schnackenburg, eds., The Mystery of the Young Rembrandt, exh. cat. (Wolfratshausen: Minerva Hermann Farnung, 2001), 64–65; Jeroen Giltaij, Rembrandt Rembrandt, exh. cat. (Frankfurt: Städelsches Kunstinstitut, 2003), 46; and Roelof van Straten, Young Rembrandt: The Leiden Years, 1606–1632 (Leiden: Foleor, 2005), 103. ↩︎

-

Ernst van de Wetering et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 4, The Self-Portraits (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005), 164 and 173. Van de Wetering (p. 601) also refers to dendrochronological evidence that indicates, in the mind of Peter Klein, that the earliest felling date is 1590. ↩︎

-

Christopher Wright declared it to be the most copied self-portrait; see Christopher Wright, Rembrandt: Self-Portraits (London: Gordon Fraser, 1982), 19. Two self-portraits, however, surpass it in the number of copies—the self-portrait of 1652 in Vienna and the self-portrait of about 1669 in Florence—according to the statistics given in the Corpus. Of the five versions of the Clowes painting with dimensions documented in the Corpus, the panel in Indianapolis is the smallest. Between the versions documented in the Corpus and those found in the RKD photo archive, at least 16 painted and printed versions of the composition from various periods are known. The subtle variations among them, including whether they contain pimples along the jawline or not, suggest that they might not have all been made after a single original. ↩︎

-

On the attribution of these versions to other artists, see Kurt Bauch, Die Kunst des jungen Rembrandt (Heidelberg: Carl Winters Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1933), 209; Abraham Bredius, Rembrandt: The Complete Edition of the Paintings, revised by Horst Gerson, 3rd ed. (London: Phaidon, 1969), 547; Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, 100 Masterpieces of Painting: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 96; Anthony F. Janson, “Rembrandt in the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 12; Akihiro Ozaki, “MOA bijutsukan shozō no ‘Renburanto no jigazō ni kansuru isshiron—Renburanto aruiwa Dau ka” [A Preliminary Discourse on the “Rembrandt Self-Portrait” in the Collection of the MOA Museum: Rembrandt or Dou?], Bunkakiyou 27 (February 1988): 1–26; Akihiro Ozaki, “A New Look at the Bust of a Young Man in the MOA Museum,” Art History (Tohoku University, Kawauchi, Japan) 11, no. 3 (1989): 4; Claus Grimm, Rembrandt selbst. Eine Neubewertung seiner Porträtkunst (Stuttgart and Zurich: Belser Verlag, 1991), 28; Leonard J. Slatkes, Rembrandt: Catalogo completo dei dipinti (Florence: Cantini, 1992), 355; Anthony F. Janson, “Rembrandt and the Museum: Jan Lievens, Part II,” Previews [North Carolina Museum of Art] (Summer 1992): 12; Helga Gutbrod, Lievens und Rembrandt. Studien zum Verhältnis ihrer Kunst, Ars Faciendi 6 (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1996), 205; and Ernst van de Wetering and Carin van Nes (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 6, Rembrandt’s Paintings Revisited: A Complete Survey (Dordrecht: Springer, 2015), 488. ↩︎

-

See Sotheby’s, New York, sale 16 May 1996, no. 28. Additional versions have been recorded in the Pacully collection in Paris (Corpus, copy 2), the James Hope collection in New York (Corpus, copy 3), the Gatchina Palace (Corpus, copy 4), and in the Musée Réattu in Arles (Corpus, copy 6, attributed to Alexis Grimou). In addition, the Corpus records an anonymous etching (after the Monte Carlo version while in the Saint-Saphorin collection) and a mezzotint by Johann Bernard (1784–after 1820) (after Corpus, copy 5). See Josua Bruyn et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 1, 1625–1631 (The Hague, Boston, and London: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), 235–240. ↩︎

-

Josua Bruyn et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 1, 1625–1631 (The Hague, Boston, and London: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), 234. ↩︎

-

Jørgen Wadum, “Rembrandt under the Skin: The Mauritshuis Portrait of Rembrandt with Gorget in Retrospect,” Oud Holland 114, nos. 2/4 (2000): 180. ↩︎

-

Eric Jan Sluijter, “The Tronie of a Young Officer with a Gorget in the Mauritshuis: A Second Version by Rembrandt Himself?” Oud Holland 114, nos. 2/4 (2000): 188–190. ↩︎

-

David A. Miller, “Conservation Laboratory Examination Techniques and Conservator’s Report,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 27–28. ↩︎

-

Miller writes, for example, that the jaw is composed of a white underpaint scumbled over with umber and black pigments, on top of which skin tones and a transparent red layer have been added in the cheeks and lips. See David A. Miller, “Conservation Laboratory Examination Techniques and Conservator’s Report,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 27. ↩︎

-

As Ernst van de Wetering has outlined, the monogram of “RHL” appears only for a short time during Rembrandt’s Leiden period. His chronology localizes this monogram to the years 1628–1629, which is consistent with Miller’s findings. See Ernst van de Wetering, “Rembrandt Laughing, c. 1628—A Painting Resurfaces,” Kroniek van het Rembrandthuis (2007): 24. ↩︎

-

Van de Wetering also notes that the definition of the jawline was originally stronger and that the inner corner of the proper right eye displayed a greater degree of red during an earlier campaign. See Ernst van de Wetering et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 4, The Self-Portraits (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005), 600. In the most recent volume of the Corpus, Van de Wetering uncovers a new pentimento, noting that the jawline was “originally accentuated with radioabsorbent paint” so as to emphasize the jawline as a transition from neck to cheek. See Ernst van de Wetering and Carin van Nes (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 6, Rembrandt’s Paintings Revisited: A Complete Survey (Dordrecht: Springer, 2015), 488. ↩︎

-

As Van de Wetering has noted, the Atami version also omits the two pimples along the sitter’s jawline, just as the Kassel copy omits the blemishes found in the Rijksmuseum original. See Ernst van de Wetering et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 4, The Self-Portraits (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005), 601. Interestingly, a pimple may also be found on Lievens’s portrait of Rembrandt (fig. 3), as well as in his self-portrait in Washington, DC. ↩︎

-

Jørgen Wadum, “Rembrandt under the Skin: The Mauritshuis Portrait of Rembrandt with Gorget in Retrospect,” Oud Holland 114, nos. 2/4 (2000): 164. ↩︎

-

Several authors have observed the absence of discussion of these self-portraits by seventeenth-century writers and art lovers: Ernst van de Wetering, “The Multiple Functions of Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits,” in Christopher White and Quentin Buvelot, eds., Rembrandt by Himself, exh. cat. (The Hague: Royal Cabinet of Paintings, Mauritshuis, 1999), 11; and Charles Ford, “Works Do Not Make an Oeuvre: Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits as a Category,” in Alan Chong and Michael Zell, eds., Rethinking Rembrandt (Zwolle: Waanders, 2002), 121. ↩︎

-

See Christopher Wright, Rembrandt: Self-Portraits (London: Gordon Fraser, 1982); Svetlana Alpers, Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988); H. Perry Chapman, Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits: A Study in Seventeenth-Century Identity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990); Ernst van de Wetering, “The Multiple Functions of Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits,” in Christopher White and Quentin Buvelot, eds., Rembrandt by Himself, exh. cat. (The Hague: Royal Cabinet of Paintings, Mauritshuis, 1999), 8–37; Ernst van de Wetering, “Rembrandt’s Hidden Self-Portraits,” Kroniek van het Rembrandthuis nos. 1/2 (2002): 2–15; and Ernst van de Wetering, “Rembrandt Laughing, c. 1628—A Painting Resurfaces,” Kroniek van het Rembrandthuis (2007): 18–40. ↩︎

-

The presence of a monogram, for instance, suggests that the painting was ultimately destined to leave the studio. ↩︎

-

See, for example, Svetlana Alpers, Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 120. Ernst van de Wetering has posited that their relevance diminished over time as the master himself aged, providing an ample opportunity for Rembrandt to have his students convert them into character heads, or tronies. See Ernst van de Wetering, “Rembrandt’s Hidden Self-Portraits,” Kroniek van het Rembrandthuis nos. 1/2 (2002): 7. ↩︎

-

Dickey observed a comparable motif in Simon Vouet’s (1590–1649) Portrait of a Young Man (Arles, Musée Réattu) of about 1615; see Stephanie S. Dickey, Rembrandt Face to Face, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2006), 51. ↩︎

-

Rudi Ekkart places the beginning of Huygens’s autobiography, in which he records his admiration for Rembrandt, in May 1629. See Rudolf E.O. Ekkart, “Rembrandt, Lievens en Constantijn Huygens,” in Christiaan Vogelaar et al., Rembrandt & Lievens in Leiden: “Een jong en edel schildersduo,” exh. cat. (Waanders: Zwolle, 1991), 49. Huygens demonstrates Rembrandt’s evocative emotions in his ekphrasis of Rembrandt’s Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver of about 1630 (Private collection): “The gesture of that one despairing Judas (not to mention all the other impressive figures in the painting), that one maddened Judas, screaming, begging for forgiveness, but devoid of hope, all traces of hope erased form his face; his gaze wild, his hair torn out by the roots, his garments rent, his arms contorted, his hands clenched until they bleed; a blind impulse has brought him to his knees, his whole body writhing in beautiful hideousness.” As cited in Christiaan Vogelaar et al., Rembrandt & Lievens in Leiden: “Een jong en edel schildersduo,” exh. cat. (Waanders: Zwolle, 1991), 132–133. ↩︎

-

As quoted in Ernst van de Wetering, “The Multiple Functions of Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits,” in Christopher White and Quentin Buvelot, eds., Rembrandt by Himself, exh. cat. (The Hague: Royal Cabinet of Paintings, Mauritshuis, 1999), 21. ↩︎

-

“I know nobody who has varied his sketches of one and the same subject in so manifold a fashion.” As cited in H. Perry Chapman, “Reclaiming the Inner Rembrandt: Passion and the Early Self-portraits,” in Stephanie S. Dickey and Herman Roodenburg, eds., The Passions in the Arts of the Early Modern Netherlands, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 60 (Zwolle: Waanders, 2010), 242. ↩︎

-

Interestingly, Ernst van de Wetering titles this work Study in the Mirror (Human Skin) in his final volume of the Corpus. See Ernst van de Wetering and Carin van Nes (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 6, Rembrandt’s Paintings Revisited: A Complete Survey (Dordrecht: Springer, 2015), 488. ↩︎

-

In her discussion of the Atami painting, Chapman describes it as the artist’s first self-portrait in martial disguise. See H. Perry Chapman, Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits: A Study in Seventeenth-Century Identity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 37. A precedent may be found in Giorgione’s (1477–1510) Self-Portrait as David (1500–1510, Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum); see Chapman, Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits, 43, and Stephanie S. Dickey, Rembrandt Face to Face, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2006), 52–58. ↩︎

-

On the tronie, see Jaap van der Veen, “Faces from Life: Tronies and Portraits in Rembrandt’s Painted Oeuvre,” in Albert Blankert et al., Rembrandt: A Genius and His Impact, exh. cat. (Zwolle: Waanders, 1997), 69–80; Dagmar Hirschfelder, Tronie und Porträt in der niederländischen Malerei des 17. Jahrhunderts (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2008); and Franziska Gottwald, Das Tronie: Muster, Studie, Meisterwerk; Die Genese einer Gattung der Malerei vom 15. Jahrhundert bis zu Rembrandt (Munich and Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2011). ↩︎

-

Dendrochronological analysis carried out by Peter Klein, in fact, connects the IMA painting to a head of an old woman executed by an artist in his circle. See Ernst van de Wetering et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 4, The Self-Portraits (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005), 649 and 653, and the catalogue entry on Rembrandt’s Mother (JL-106) in the catalogue of The Leiden Collection. ↩︎

-

Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century, vol. 6 (London: Macmillan and Co., 1916), no. 549, cites this early provenance, however the authors of the Rembrandt Research Project believe it applies to a version formerly in the collection of the Swiss de Mestral de Saint-Saphorin family that is now in a private collection in Monte Carlo. See Josua Bruyn et al. (Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 1, 1625–1631 (The Hague, Boston, and London: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), 239–40.

For a comprehensive examination of the provenance, exhibition, and publication history of the Clowes painting, see Stephanie S. Dickey, Rembrandt Face to Face (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2006), 67–70. ↩︎

-

See Jerzy Mycielski, “Odczt Prof. Dra Jerzego Mycielskiego wygloszony dnia 21. Lutego 1909 w salach wystawy” [The Lecture of Professor Jerzy Mycielski Delivered on February 21, 1909, in the Exhibition Rooms], in Album de l’exposition des maîtres anciens, avec cinquante reproductions, ed. Miecislas Treter, exh. cat. (Lvov: Ossoliński National Institute/Gubrynowicz et Fils, 1911), 51–65, and Leon Pininski, “Przemowienie Leona hr. Pininskiego wygloszone przy otwarciu wystawy dnia 17. Lutego 1909 r.” [The Speech by Count Leon Pininski Delivered on the Opening of the Exhibition on February 17, 1909], in Album de l’exposition des maîtres anciens, avec cinquante reproductions, ed. Miecislas Treter (Lvov: Ossoliński National Institute/Gubrynowicz et Fils, 1911), 43–50. ↩︎

-

According to Arkadiusz Dobrzyniecki, Ossoliński Institute, Lvov, the Clowes painting descended through the Husarzewski family, its earliest confirmed owners, not through the Lubomirski lineage. Dobrzyniecki also noted that it was exhibited in the Lvov Picture Gallery (now Lvov Art Gallery) for an indeterminate length of time during WWII, and that Jerzy (George/Georges) Lubomirski sold works of art that had come into his possession; Arkadiusz Dobrzyniecki, email message to Stephanie Dickey and Ronda Kasl, 21 and 24 April 2006. ↩︎

-

See Letter from Clyde Newhouse to G.H.A. Clowes, 3 April 1951, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. For additional correspondence see also File C10063, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

The Clowes painting was exhibited only on the first day of the Panorama exhibition at the Indianapolis Museum of Art Columbus. See File C10063, Registration Historical Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

I would like to thank Junko Aono, Kyushu University, for her assistance in translation. ↩︎