Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

Signed and dated, lower left, in dark brown paint: BRVEGHEL 1612

Inscribed, lower right, in ocher-brown paint: 708.

Entry

Author

Provenance

Van der Houven family.36

Jacob (“Jacomo”) de Wit (or de Witte, about 1650–1721), Antwerp, by 1710;37

Augustus II, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland (1670–1733), in 1710;38

By descent to Frederick Augustus I, Elector of Saxony (1750–1827);

Königliche Gemäldegalerie, Dresden, about 1806 and until 1919;39

Staatliche Gemäldegalerie, Dresden, 1919 to 1924;40

House of Wettin, Albertine line (Verein Haus Wettin Albertinischer Linie e.V.), in 1924.41

Probably (Drey Gallery, London), after 1924.42

(Newhouse Galleries, Inc. New York);

Edith Whitehill Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1958;43

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2000 and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10011);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2000 (2000.343).

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 10.

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame Art, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 8.

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1962, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 25.

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, 1965, Le Siècle de Rubens, no. 21.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 1997, Pieter Breughel der Jüngere, Jan Brueghel der Ältere: Flämische Malerei um 1600, Tradition und Fortschritt, no. 61.

Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, China; Hunan Museum, Changsha, China; Chengdu Museum; 2020–2021, Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting.

References

Johann Adam Steinhäuser, Inventory of the art collection of Augustus II (1670–1733), titled “Lit. A et B. Inventaria Sr. Königl. Majestät in Pohlen und Churfürstl. Durchl. zu Sachsen große, wie auch kleine Cabinets und andere Schildereyen,” 1722–1728, Handschrift, Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden, 13458 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Nr. 356, Lit. A, fol. 18r, no. 708 (as “Flut Breugel …or[iginal]…Landschaft mit vielen Waßer u. Fahrzeugen…[Hōhe] 16. [Zoll] [Breite] 1. [Fuß] 2. [Zoll]…[geliefert] de Wit”);

Johann Adam Steinhäuser, Inventory (called “vor 1741” or “Steinhäusers Inventar”) of the art collection of Augustus II (1670–1733), titled “S.r königl. Maj.t in Pohlen, und chursfürstl. Durchl. zu Sachsen, Schildereij-Inventaria sub lit. A. et B.,” 1741–1747, Handschrift, Archiv der SKD (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister), Nr. 357, fol. 140, no. 708 (as “Flut Breugel…or[iginal]…mitten Baum u. Schiffe mit Menschen…[Hōhe] 16 [Zoll] [Breite] 1. [Fuß] 2. [Zoll]…[auf] H[olz]") and fol. 311 (as having come from “de Witt”);

Possibly listed in Neues Sach- und Ortsverzeichniss der königlich sächsischen Gemälde-Gallerie zu Dresden (Dresden, 1826), 120, no. 702 (as “Ein schönes Dorf an einem Canale, dessen Ufer mit Bäumen besetzt sind. Im Vorgrunde liegen Fahrzeuge, um welche sich viele Menschen beschäftigen. Auf H. 2 F. 3 Z. br. 1 F. 2 Z. b.");

Possibly listed in Catalogue des tableaux de la Galerie royale de Dresde (Dresden, 1826), 108, no. 702 (as “Un beau village près d'un large canal, bordé d'arbres. Le devant du tableau montre plusieurs barques et vaisseaux avec beaucoup de monde. Sur b. 2' 3" de l. 1' 4½" de h.");

Possibly listed in Neues Sach- und Ortverzeichniss der Königlich-Sächsischen Gemälde-Gallerie zu Dresden (Dresden, 1833), 120, no. 702 (as “Ein schönes Dorf an einem Canale, dessen Ufer mit Bäumen besetzt sind. Im Vorgrunde liegen Fahrzeuge, um welche sich viele Menschen beschäftigen. Auf H. 2 F. 3 Z. br. 1 F. 2½ Z. b.");

Probably listed in Friedrich Matthäi, Verzeichniss der Königlich Sächsischen Gemälde-Galerie zu Dresden (Dresden: Gärtner, 1837), 217, as either no. 1099 (“Ein schönes Dorf an einem Kanale, dessen Ufer mit Bäumen besetzt sind. Im Vorgrunde liegen Fahrzeuge, um welche sich viele Menschen beschäftigen. Auf H. 2 F. 3 Z. br. 1 F. 2½ Z. h.") or no. 1100 (“Landschaft mit einem breiten Strome, an dessen Ufer mehrere Häuser, deren zahlreiche Bewohner auf mancherlei Art beschäftigt sind; viele Schiffe segeln auf dem Flusse, andere liegen am Ufer. Auf H. 2 F. 3½ Z. br. 1 F. 3 Z. h.");

Probably listed in Verzeichniss der königlichen Gemälde-Galerie zu Dresden (Dresden: Ernst Blochmann und Sohn, 1844), 170, as either no. 1412 (“Ein schönes Dorf an einem Kanale, dessen Ufer mit Bäumen besetzt sind. Auf L. [sic] 1' 2½″ h. 2' 3″ br.") or no. 1414 (“Landschaft mit einem breiten Strome, an dessen Ufer mehrere Häuser; viele Schiffe segeln auf dem Flusse, andere liegen am Ufer. Auf H. 1' 3″ h. 2' 3½″ br.");

Probably listed in Catalogue des tableaux de la Galerie royale de Dresde (Dresden: Ernest Blochmann & fils, 1846), 163, as either no. 1412 (“Village près d'un canal bordé d'arbres. S. t. [sic], h. 1' 2½″ – l. 2' 3″") or no. 1414 (“Paysage hollandais traversé par un large fleuve. S. b., h. 1' 3″ – l. 2' 3½″");

Probably listed in Catalog der königlichen Gemälde-Galerie zu Dresden (Dresden: Ernst Blochmann und Sohn, 1848), 154, as either no. 1412 or 1414 (with the same descriptions and catalogue numbers as in the 1844 catalogue);

Probably listed in the Catalog der königlichen Gemälde-Galerie zu Dresden (Dresden: Ernst Blochmann und Sohn, 1853), 154, as either no. 1412 (with the same description and catalogue number as in the 1844 catalogue) or no. 1414 (“Holländische Landschaft, auf deren breitem Strome Schiffe segeln. Auf H. 1' 3″ h. 2' 3½″ br.");

Probably listed in Jules Hübner, Catalogue de la Galerie royale de Dresde (Dresden: E. Blochmann et fils, 1856), either on p. 180, no. 700 (“Beau village près d'un canal bordé d'arbres. S. t. [sic], h. 1' 2½” — l. 2' 3" 1722 à la foire de Pâques à Leipzig comme de Momper et de Breughel. Anc. inv. 1722”) or on p. 181, no. 702 (“Paysage hollandais, avec un canal parcouru par des vaisseaux. S. b., h. 1' 3" — l. 2' 3½" 1710 acq. par Raschke de Jac. de Wit à Anvers; 300 pistoles”);

Probably listed in Jules Hübner, Verzeichniss der königlichen Gemälde-Gallerie zu Dresden (Dresden: Liepsch & Reichardt, 1856), 179, as either no. 700 (“Ein schönes Dorf an einem Kanale, dessen Ufer mit Bäumen besetzt sind. Auf L. [sic] 1' 2½” h. 2' 3” br. Ostermesse 1722 in Leipzig als Momper u. Breughel. Alt Inv. 1722.") or no. 702 (“Holländische Landschaft. Auf einem Kanale segeln Schiffe. Auf H. 1' 3" h. 2' 3½" br. 1710 durch Raschke von Jac. de Wit in Antwerpen; 300 Pistolen”);

Probably listed in Die Königliche Gemälde-Gallerie im Neuen Museum zu Dresden (Dresden: H. Klemm’s Verlag, 1860), either on p. 684, as no. 700 (“Eine reiche Landschaftscomposition in nettester Behand lung der Architectur wie der Staffage. Fast wie Tempera behandelt. Ein ansehnliches Kirchdorf, das am theilweise mit hochstämmigen Bäumen besetzten Ufer eines breiten Canals gelegen ist und einen frequenten Ausschiffungsplatz hat. Am Ufer selbst, sowie auf dem Wasser und vor den Häusern ist einiger Verkehr in lebendiger, buntester Situation, deren nähere Betrachtung uns J. Breughel als einen höchst gewandten Figurenzeichner documentirt. Das B. ward bereits 1722 auf der Leipziger Ostermesse für den König August II. angekauft, und zwar als ein Gemälde, dessen Landschaft von Momper und dessen Staffage blos von Breughel herrühren solle [sic]. Es kam erst um 1806 zur Gall. Leinw. [sic], 1 F. 2½ Z. hoch, 2 F. 3 Z. breit”) or on p. 690, as no. 702 (“Flusslandschaft nebst grosser Ortschaft. An einem breiten Strome, der durch mancherlei Fahrzeuge mit und ohne Segel, Aaken, Lastkähne, Boote etc. belebt ist, liegen beiden Ufern [sic?] Ortschaften und Städte nebst angelegten Transportschiffen. Im Vordergrunde rechts eine bis zum Mittelgrunde sich erstreckende Gasse einer wahrscheinlich niederrheinischen Dorfschaft, mit Frequenz von Fuhrwerk, Vieh etc. Rechts vor den Häusern Verkehr von Schiffsvolk, Bauern und noblen Reitern, sowie am Ufer Fischverkauf. Dieses namentlich mehr nach Art der Tempera behandelte und in der dem Meister so beliebten, zeichnenden Ausführung vollendete Bild ward 1710 durch Vermittelung des Premier-Commissair Raschke vom Kunsthändler Jacques de Witte für den König August II. um 300 Pistolen angekauft, kam jedoch erst gegen 1806 zur Gall. - Holz, 1 F. 3 Z. hoch, 2 F. 3½ Z. breit”);

Julius Hübner, Catalogue de la Galerie royale de Dresde, 2nd ed. (Dresden: E. Blochmann et fils, 1862), 217, no. 737 (as “Beau village près d'un canal bordé d'arbres. S. t. [sic], h. 1' 2½” — l. 2' 3" Acheté en 1722 à la foire de Pâques à Leipzig comme de Momper et de Breughel [sic]. Anc. inv. de 1722”);

Julius Hübner, Verzeichniss der Königlichen Gemälde-Gallerie zu Dresden, 2nd ed. (Dresden: E. Blochmann & Sohn, 1862), 213, no. 737 (as “Ein schönes Dorf an einem Canale, dessen Ufer mit Bäumen besetzt sind. Auf L. [sic] 1' 2½" h. 2' 3” br. Bez. BRVEGHEL 1612. Ostermesse 1722 in Leipzig als Momper und Brueghel [sic]. Alt. Inv. 1722”);

Julius Hübner, Verzeichniss der Königlichen Gemälde-Gallerie zu Dresden, 3rd ed. (Dresden: E. Blochmann & Sohn, 1867), 184, no. 737 (with the same description as in the 1862 catalogue);

Julius Hübner, Catalogue de la Galerie royale de Dresde, 3rd ed. (Dresden: E. Blochmann et fils, 1868), 186, no. 737 (with the same description as in the 1862 catalogue);

Julius Hübner, Verzeichniss der Königlichen Gemälde-Gallerie zu Dresden, 4th ed. (Dresden: E. Blochmann und Sohn, 1872), 190, no. 737 (“Ein schönes Dorf an einem Canale, dessen Ufer mit Bäumen besetzt sind. Auf H. 0,375 h., 0,615 br. Bez. BRVEGHEL 1612. Ostermesse 1722 in Leipzig als Momper und Brueghel [sic]. Alt. Inv. 1722”);

Complete Catalogue of the Royal Picture Gallery at Dresden (Dresden: G. Schönfeld's Buchhandlung, 1873), 32, under nos. 734–738 (“Dutch landscapes. W. and C. [1608–1613]. 20a”);

Julius Hübner, Catalogue of the Royal Picture Gallery in Dresden, with Notices Concerning the Acquisition and Signatures of the Paintings, trans. J. Pond (Dresden: B.G. Teubner, 1874), 105, no. 737 (as “A beautiful village on a canal, the banks of which are ornamented with trees. On wood, 0,375 h., 0,615 w. Signed: BRVEGHEL 1612. Purchased in 1722 at the Easter Fair, as Momper and Brueghel [sic]. Old inven. 1722”);

Julius Hübner, Catalogue of the Royal Picture Gallery in Dresden, with an Historical Introduction and Notices Concerning the Acquisition and Signatures of the Paintings, 5th ed., trans. J. Pond (Dresden: W. Hoffmann, 1880), 205, no. 813 (with the same description as in the 1874 catalogue);

Julius Hübner, Verzeichniss der Dresdner Gemälde Gallerie, 5th ed. (Dresden: B.G. Teubner, 1880), 232, no. 813 (with the same description as in the 1872 catalogue);

Julius Hübner, Verzeichniss der Königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden (Dresden: Wilhelm Hoffmann, 1884), 214, no. 813 (with the same description as in the 1872 catalogue);

Julius Hübner, Catalogue of the Royal Picture Gallery in Dresden, with an Historical Introduction, Notices Concerning the Acquisition and Signatures of the Paintings, and a Price-List of Engravings from Pictures in the Gallery, 5th ed., trans. J. Pond (Dresden: William Hoffmann, 1884), 208, no. 813 (with the same description as in the 1874 catalogue);

Karl Woermann, Catalogue of the Royal Picture Gallery in Dresden, trans. B.S. Ward (Dresden: Wilhelm Hoffmann, 1887), 106, no. 888 (as “Dutch canal with a village and church. Signed: BRVEGHEL. 1612. Q 1. — (813) — W. — 0,37 h.; 0,61½ w.");

Karl Woermann, Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden: Kleine Ausgabe (Dresden: Wilhelm Hoffmann, 1887), 103, no. 888 (as “Niederländischer Kanal mit einem Kirchdorf. — Bezeichnet: BRVEGHEL. 1612. Q 1. — (813) — H. — h. 0,37; br. 0,61½”);

Karl Woermann, Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden: Große Ausgabe, 2nd ed. (Dresden: Bruno Schulze, 1892), 297, no. 888 (as “Niederländischer Kanal. Links der Kanal mit baumreichen Ufern. Rechts vorn und im Mittelgrunde ein Kirchdorf, in dem ein Fährboot landet. Andere Fahrzeuge am Ufer. Bezeichnet links unten: BRVEGHEL. 1612. Eichenholz: h. 0,37; br. 0,61½ – 1710 von Jak. de Wit in Antwerpen. Inv. 1722, A 708. [Die Inventarnummer steht drauf; die Angabe bei H. war daher nicht richtig.]");

Karl Woermann, Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden, 3rd ed. (Dresden: Albanus, 1896), 298, no. 888;

Karl Woermann, Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden: Grosse Ausgabe, 4th ed. (Dresden: Wilhelm Hoffmann Kunstanstalt auf Aktien, 1899), 296, no. 888;

Karl Woermann, Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden: Grosse Ausgabe, 5th ed. (Dresden: W. Hoffmann, 1902), 291, no. 888;

Karl Woermann, Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden, 6th ed. (Dresden: W. Hoffman, 1905), 291, no. 888;

Karl Woermann, Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden: Große Ausgabe, 7th ed. (Dresden: W. Hoffmann, 1908), 295, no. 888;

Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden, 8th ed. (Dresden: Wilhelm und Bertha von Baensch Stiftung, 1912), 96, no. 888;

Hans Posse, Katalog der Staatlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden: Kleine Ausgabe, 10th ed. (Dresden: Wilhelm und Bertha von Baensch Stiftung, 1920), 104, no. 888;

Yvonne Thiéry, Le paysage flamand au XVIIe siècle (Brussels: Elsevier, 1953), 177 (as “1612 Vue de Canal. Toile [sic], 37 × 61 cm. Dresde, Galerie de peinture, no. 888”);

Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), cat. 10, unpaginated (reproduced);

A Lenten Exhibition: Loaned by the Clowes Fund, Incorporated of Indianapolis, exh. cat. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Art Gallery, 1962), cat. 8, unpaginated;

Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, exh. cat. (Bloomington: Indiana University Art Museum, 1963), cat. 25, unpaginated ;

Le Siècle de Rubens, exh. cat. (Brussels: Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique 1965), 23, cat. 20 (reproduced);

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

European Paintings from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1971), 139, under cat. 73;

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 118–119, 189 (reproduced);

Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann and Kent Ahrens, Wadsworth Atheneum Paintings, Catalogue I: The Netherlands and the German-Speaking Countries, Fifteenth-Nineteenth Centuries (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1978), 123, fig. 8, under cat. 21;

Jan Brueghel the Elder: A Loan Exhibition of Paintings, 21 June–20 July, 1979 (London: Brod Gallery, 1979), 62, under cat. 12;

Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 186, 600–601, cat. 257 (as a later autograph version of the painting at the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp, inv. no. 910);

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, 100 Masterpieces of Painting: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 82–83 (reproduced);

Bruegel: Une dynastie de peintres, exh. cat. (Brussels: Palais des beaux-arts, 1980), 190;

Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625) (Cologne: DuMont, 1981), 96, under cat. 21;

Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Jüngere (1601–1678): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog, vol. 1 (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1984), 219, under cat. 35;

Klaus Ertz, 17th Century Netherlands Painting: Galerie d’art St. Honoré Exhibition Octobre 1985, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie d’art St. Honoré, 1985), 30, under cat. 12;

Klaus Ertz, The Brueghel Family of Painters and Further Masters from the Golden Age of Netherlandish Painting, Galerie d’art St. Honoré, exh. cat. (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1986), 32, under cat. 12;

Yvonne Thiéry and Michel Kervyn De Meerendré, Les peintres Flamands de paysage au XVIIe siècle: Le baroque anversois et l’école bruxelloise (Brussels: Lefebvre & Gillet, 1987), 30, 31 (reproduced);

Richard H. Saunders, John Smibert: Colonial America’s First Portrait Painter (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 122, 123, fig. 132;

Pieter Breughel der Jüngere, Jan Brueghel der Ältere: Flämische Malerei um 1600; Tradition und Fortschritt, ed. Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, exh. cat. (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 1997), 224–225, cat. 61;

Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde, (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008) 1:245–250, 378, 386, cat. 107;

Leopoldine Prosperetti, Landscape and Philosophy in the Art of Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625) (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), viii, 16, fig. 1.11, 27, under note 68;

Kjell M. Wangensteen et al., Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 148–153 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen et al., Floating Lights and Shadows: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 150–155 (reproduced).

Notes

-

In his account of Duke Johann Ernst of Saxony’s visit to Antwerp in 1614, Johann Wilhelm Neumayr rates Brueghel and Peter Paul Rubens as the city’s preeminent painters. Of the former, he notes, “Brügel…mahlet kleine Täfflein mit Landschafften, aber alles so subtil und künstlich, daß mans mit Berwunderung ansehen muß.” J.W. Wilhelm Neumayr von Ramssla, Des durchlauchtigsten Herrn. Joh. Ernst d. jüng. Hertzogen zu Sachsen, Reise in Frankreich, Engelland und Niederland (Leipzig, 1620), 261. Likewise, Anthony van Dyck, in his famous Iconographie (Antwerp, 1645), included a portrait of Brueghel bearing the inscription “ANTVERPIÆ PICTOR FLORVM ET RURALIVM PROSPECTVVM.” ↩︎

-

See in particular Ertz’s 1979 catalogue raisonné, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979). See also Fredericke Klauner, “Zur Landschaft Jan Brueghels d.Ä.,” Nationalmusei årsbok 19/20 (1949): 5–28. More recently, Leopoldine Prosperetti has situated Brueghel’s landscapes within the rhetorical and philosophical milieu of early seventeenth-century Antwerp: see Leopoldine Prosperetti, Landscape and Philosophy in the Art of Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625) (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009). ↩︎

-

As an indication of the sheer variety of Brueghel’s landscapes, Klauner traces Brueghel’s subsequent development from the world landscape into six unique subcategories: forest interiors, river landscapes, ice-skating scenes, village streets, forest paths, and wide landscapes. See Fredericke Klauner, “Zur Landschaft Jan Brueghels d.Ä.,” Nationalmusei årsbok 19/20 (1949): 5–28. Ertz divides Brueghel’s landscape oeuvre into seven groups: the multiground landscape (“Mehr-Gründe-Landschaft”), the world landscape (“Weltlandschaft”), the spatial alleyway landscape (“Raumgassenlandschaft”), the near-far landscape (“Nah-Fern-Landschaft”), the wedge-shaped deep space landscape (“Keilförmige Tiefenraumlandschaft”), the vanishing-point landscape (“Fluchtpunktlandschaft”), and the flat landscape (“Flachlandschaft”); see Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 24–66. Within the broad category of Brueghel’s water landscapes, Ertz distinguishes three “old-fashioned” types (world water landscapes, water landscapes with ancient ruins, and wide river landscapes), and four “modern” types (the frontal village canal, meadow brooks, river landscapes with a jetty, and “pure” seascapes); see Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 169–189. Ertz considers the present example as one of the latter (i.e., “modern”) landscapes, classifying it under the narrow subcategory of river landscapes with a jetty on the right bank; see Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 186–189. ↩︎

-

A comparable compositional arrangement (though with the river on the right and the road on the left) is found in Brueghel’s 1598 Landscape with the Young Tobias (Vaduz/Vienna, Collection of the Princes of Liechtenstein). As Ertz notes, the roads in Brueghel’s landscapes frequently serve the same function as the rivers, that is, to create spatial alleyways (“Raumgassen”). Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 42. ↩︎

-

On this point, see Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008), 1:245–250. ↩︎

-

Brueghel repeatedly employed this scheme in his drawings, as in his River Landscape of about 1600 (Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. nr. 19.730), his Seascape with Boats, of about 1605 (Nationalmuseum Stockholm, inv. nr. NMH THC 3236), and his 1620 drawing Canal with Sailboats and Cattle (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, inv. KdZ 5734). ↩︎

-

Compare, for example, the rivers depicted in Patinir’s Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx (Madrid, Prado Museum), Bol’s 1586 miniature Abraham and the Three Angels (Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister), and Bruegel’s lost The Unfaithful Shepherd, a copy of which is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Though it proceeded the development of Weltlandschaft, the Ecce Agnus Dei of Dieric Bouts (about 1462–1464, Munich, Alte Pinakothek) might also be considered in this regard. On Brueghel’s debt to, and innovations of Weltlandschaft, see Fredericke Klauner, “Zur Landschaft Jan Brueghels d.Ä.,” Nationalmusei årsbok 19/20 (1949): 5–28. ↩︎

-

Jan Brueghel the Elder, after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Baasrode River Landscape, about 1600, pen and brown ink on paper, 20 × 31.9 cm, London, The British Museum, inv. 1946.0713.148. Cf. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Baasrode River Landscape, about 1555, pen and brown-gray ink, 24.9 × 42.1 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, inv. no. KdZ 5763. There are only minor differences between the two drawings. Though Popham attributed the British Museum sheet to the father, subsequent scholars have generally credited it to the son. See the exhibition catalogue Jan Brueghel: A Magnificent Draughtsman (Antwerp: Snijders & Rockox House, 2019), 53–56. Cf. Arthur E. Popham, Catalogue of Drawings in the Collection Formed by Sir Thomas Phillipps, bart., F.R.S., now in the Possession of His Grandson, T. FitzRoy Phillipps Fenwick of Thirlestaine House, Cheltenham (London, 1935), 179–180. ↩︎

-

On this point, see especially Klaus Ertz, “Die Fluss-und Dorflandschaft,” in Die flamische Landschaft, 1520–1700: Eine Ausstellung der Kulturstiftung Ruhr Essen und des Kunsthistorischen Museums Wien, ed. Klaus Ertz, Hanna Benesz, and Wilfried Seipel (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2003), 184–191. On Brueghel’s application of perspectival conventions to his river scenes in particular, see the exhibition catalogue Jan Brueghel: A Magnificent Draughtsman (Antwerp: Snijders & Rockox House, 2019), 53–71, and the literature cited there. ↩︎

-

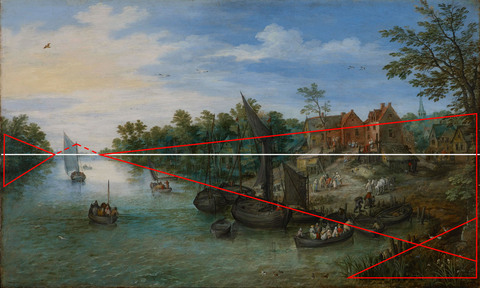

A slightly different triangular construction of the painting is illustrated in Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008), 1:247, fig. 1. Compare Ertz’s diagram of the Antwerp version, now attributed to Jan Brueghel the Younger, in Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 53, fig. 6. ↩︎

-

Jan Brueghel the Elder, Canal with Sailing Boats and Cattle, 1620, pen and brown ink, with gray, gray-blue, and green washes, 19.5 × 31.2 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, inv. KdZ 5734. The drawing is signed and dated in the lower-left corner. See Jan Brueghel: A Magnificent Draughtsman, exh. cat. (Antwerp: Snijders & Rockox House, 2019), 68–69, cat. 21. ↩︎

-

Here one might cite the mature landscapes of Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691), Jacob van Ruisdael (about 1629–1682), and Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709), among others. ↩︎

-

Hence his sobriquet “Fluwelen Brueghel” (Velvet Brueghel). According to Prosperetti, the nickname also connoted Brueghel’s elevated social status. See Leopoldine Prosperetti, Landscape and Philosophy in the Art of Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625) (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 18–19. On Brueghel's purchase of velvet clothes, see Emile Michel and Victoria Charles, The Brueghels (New York: Parkstone Press International, 2007), 231. On the epithet’s connection to Brueghel’s landscapes in particular, see Gertraude Winkelmann-Rhein, The Paintings and Drawings of Jan “Flower” Bruegel (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1968), 53–58. ↩︎

-

Brueghel’s Continence of Scipio (Munich, Alte Pinakothek) demonstrates Brueghel’s capable assimilation of Weltlandschaft by the year 1600. Compare also the three-color scheme of Brueghel’s contemporary and frequent collaborator Joos de Momper the Younger (1564–1635), whose Mannerist landscapes generally employ a three-color scheme, with reddish-brown colors in the foreground, blue-green tones in the middle ground, and light blues in the background. ↩︎

-

Brueghel’s pictorial conceit of alternating light and dark areas of the landscape, demarcating areas where the sun penetrates the clouds (or not), is found in numerous paintings from the 1590s, including his 1598 Sea Harbor with the Preaching Christ (Munich, Alte Pinakothek). ↩︎

-

References to a painting with a matching description in the royal collections in Dresden indicate that it may have been regarded at one time as a collaboration between Brueghel and Joos de Momper the Younger. See Die Königliche Gemälde-Gallerie im Neuen Museum zu Dresden (Dresden: H. Klemm’s Verlag, 1860), 684, under cat. no. 700: “Eine reiche Landschaftscomposition in nettester Behand lung der Architectur wie der Staffage. Fast wie Tempera behandelt. Ein ansehnliches Kirchdorf, das am theilweise mit hochstämmigen Bäumen besetzten Ufer eines breiten Canals gelegen ist und einen frequenten Ausschiffungsplatz hat. Am Ufer selbst, sowie auf dem Wasser und vor den Häusern ist einiger Verkehr in lebendiger, buntester Situation, deren nähere Betrachtung uns J. Breughel als einen höchst gewandten Figurenzeichner documentirt. Das B. ward bereits 1722 auf der Leipziger Ostermesse für den König August II. angekauft, und zwar als ein Gemälde, dessen Landschaft von Momper und dessen Staffage blos von Breughel herrühren solle.” ↩︎

-

The latest dated heartwood ring of this board is 1597. Adding the minimum expected number of sapwood rings likely to be missing (eight years for eastern Baltic sourced timber) yields an expected painting date of about 1605 or later. Ian Tyers, “Tree-Ring Analysis and Wood Identification of Paintings from the Indianapolis Museum of Art: Dendrochronological Consultancy Report 1082,” January 2019, 8–10. Conservation Department files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Jan Brueghel the Younger, River Landscape with a Jetty, signed and dated “BRVEGHEL 1603,” oil on panel, 39 × 60 cm, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, inv. nr. 910. See Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 52–55, cat. 94. ↩︎

-

Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 573, cat. 94. ↩︎

-

Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Jüngere (1601–1678): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1984) 1:218–219, cat. 35: “Wie die Brüsseler Ausstellung von 1980 eindeutig erwiesen hat, ist Kat. 35 eine von Jan II fälschlicherweise 1603 datierte Kopie nach den väterlichen Vorbildern im Museum of Art, Indianapolis (E 79, Kat. 257) und in deutschem Privatbesitz (E 79, Kat. 101, Farbabb. 215, S. 187).” Compare Bruegel: Une dynastie de peintres, exh. cat. (Brussels: Palais des beaux-arts, 1980), 190, cat. 123. See also Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008) 1:245–250, under cat. 107. ↩︎

-

“Hat eine heute unbekannte Arbeit oder eine Zeichnung mit diesem Datum existiert, die dem Sohn als Vorlage diente? Ist das Datum zufällig richtig gewählt, ist das Indianapolis-Bild von 1612 die spätere, eigentlich etwas unzeitgemäße Ausführung auf Holz in großem Format, vielleicht auf besonderen Wunsch eines fürstlichen Sammlers gemalt (bis 1920 befand sich das Indianapolis-Bild in den Dresdner Königlichen Sammlungen)? Oder aber müssen wir uns mit dem Gedanken anfreunden, dass die Antwerpener Version nicht vom Sohn nach dem Tode des Vaters gemalt wurde, sondern im Jahr 1603 im Atelier des Meisters entstand und dieser die schwächere Qualität durchgehen ließ, sie mit seiner Signatur versah und damit zum Verkauf authentisierte? Aber wo ist dann die Grenze zu den nicht eigenhändigen Bildern zu ziehen? Diese Probleme mit der Eigenhändigkeit hat das Indianapolis-Bild allerdings mit Sicherheit nicht!” Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008) 1:245–250. ↩︎

-

The painting was formerly in the Silvano Lodi Collection in Campione, Italy. See Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1979), 187, fig. 215, 574, cat. 101. Compare Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008), 1:250, cat. 108. See also Bruegel: Une dynastie de peintres, exh. cat. (Brussels: Palais des beaux-arts, 1980), 190, cat. 123a. ↩︎

-

“Wenn das Antwerpener Bild (s. Kommentar zu Kat. 107) aus dem Atelier Jan Brueghels d.Ä stammen sollte, könnte diese Miniatur diesem Gemälde möglicherweise als Versuch in kleinem Format vorausgegangen sein (wogegen allerdings das Fehlen alles Skizzenhaften, noch Unvollendeten spricht), oder sie könnte wie das Indianapolis-Beispiel (Kat. 107) wesentlich später, um 1612, entstanden sein. Am wahrscheinlichsten scheint mir die weit gefasste Datierung: um 1603–12.” Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008), 1:250, cat. 108. ↩︎

-

Jan Brueghel the Elder, A Wooded River Landscape with a Landing Stage, Boats, Various Figures, and a Village Beyond, signed and dated at lower left (“BRVEGHEL 1614”), oil on copper, 25.9 × 37 cm. Sold at auction, Sotheby’s, New York, Master Paintings Evening Sale, 1 February 2018 (sale no. N09812), lot 40. This work was formerly in the collection of the antiques dealer Joseph Altounian (1890–1954) and was previously sold (Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 30 March 1885, lot 8) with the title “L'Arrivée à la kermesse,” implying that the figures and saddled horses loaded into the boats may be headed to a local festival. ↩︎

-

Nantes, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. nr. 38. The work is signed and dated in the lower right, though the final two digits of the date are not legible. See Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008) 1:256–258, cat. 113. ↩︎

-

Jan Brueghel the Younger, River Landscape with Jetty, probably after 1625, oil on panel, 38.5 × 62.3 cm. The painting was formerly in the possession of George Brodrick, 2nd Earl of Midleton, and was sold at Sotheby’s London on 12 July 1978, lot. 86. See Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Jüngere (1601–1678): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1984) 1:218, cat. 34. A color reproduction is found in Klaus Ertz, The Brueghel Family of Painters and Further Masters from the Golden Age of Netherlandish Painting, Galerie d’art St. Honoré, exh. cat. (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1986), 31, under cat. 12. ↩︎

-

Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, inv. nr. 5624. The painting is on panel and measures 61.5 × 115.9 cm. Ertz dates the work to after 1625. See Klaus Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Jüngere (1601–1678): Die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1984) 1:221–222, cat. 38. ↩︎

-

Christie’s London, 14 May 1965, lot 90. ↩︎

-

Beginning in 1705, Bredael and his cousin Jan Frans Van Bredael (1683–1750) were employed to make copies after the works of Jan Brueghel the Elder, Philips Wouwerman, and others. According to the contract, dated 27 July 1705, Joseph van Bredael received 6 guilders for each copy he produced in the first year, 8 guilders in the second, and 10 guilders in the third and fourth years, plus a bonus of 1 shilling. As neither Joseph nor Jan Frans signed these copies, it is nearly impossible to distinguish their hands in these works. See Klaus Ertz, “Bredael (Breda), Joseph van,” in Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon (Munich: K.G. Saur, 1996) 14:55–56. Copies of the IMA’s painting (or a version thereof), all attributed to Joseph van Bredael, were sold at the following auctions: Christie's New York, 26 January 2001, lot 46 (oil on panel 31 × 40.3 cm); Sotheby’s London, 13 December 2001, lot 107 (oil on panel, 24 × 32.2 cm); Marc-Arthur Kohn, 6 March 2002, lot 47 (oil on panel, 24 × 32 cm); Beaux-Arts, 30 November 2004, lot 213 (oil on copper, 42 × 62 cm); Marc-Arthur Kohn, 25 March 2005, lot 58 (oil on panel, 24 × 32 cm, probably the same work); Sotheby’s London, 27 April 2006, lot 13 (oil on panel, 24 × 32 cm); Sotheby’s Amsterdam, 9 May 2006, lot 16 (oil on copper, 28 × 37 cm); Sotheby’s London, 22 April 2009, lot 8 (oil on copper, 39.5 × 50.5 cm); Christie’s New York, 13 January 2013, lot 307 (oil on copper, 28 × 36.9 cm); Dorotheum, 19 April 2016, lot 213 (oil on copper, 41 × 61 cm); and Christie’s London, 4 June 2019, lot 58 (oil on copper, 26.6 × 33.4 cm). ↩︎

-

Further information on this provenance is found below. ↩︎

-

Adolphe Siret, “BREDAEL, Jean-François VAN,” in Biographie nationale de Belgique (Brussels: Académie Royale de Belgique, 1868) 2:921–922. ↩︎

-

Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum, Sumner Collection, 1937.487. The painting measures 23 × 31.5 cm and is inscribed (“i BREUGHEL”) at lower right. See Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann and Kent Ahrens, Wadsworth Atheneum Paintings, Catalogue I: The Netherlands and the German-Speaking Countries, Fifteenth-Nineteenth Centuries (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1978), 123, cat. 21. ↩︎

-

These include the Village Scene with a Self-Portrait, 1614 (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv. nr. 9102) and the Village Scene with a Self-Portrait, 1616 (sold at Christie’s London, Old Masters Evening Sale, 6 July 2017, lot 42), See Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008), 1:284–289, cats. 132 and 133. ↩︎

-

The Scheldt was not fully reopened to shipping vessels until 1863. ↩︎

-

London, British Museum, inv. 1946, 0713.148. ↩︎

-

A red seal with three violins, necks upward, is present on the back of the panel. According to J.B. Rietstap’s Armorial Général, 2nd ed. (Gouda: G.B. van Goor Zonen, 1884) 1:995, this coat-of-arms belongs to the Rhenish branch of the Dutch family Van der Houven. ↩︎

-

The painting is listed in the 1722–1728 inventory of Augustus II’s collection, where the Antwerp provenance is noted. See Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden, 13458 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Nr. 356, fol. 18r, no. A 708: “Flut Breugel…or[iginal]…Landschaft mit vielen Waßer u. Fahrzeugen…[geliefert] de Wit.” The number 708 appears in ocher-brown paint on the front of the painting, at bottom right. The wealthy Antwerp merchant and art dealer Jacob de Wit (who called himself “Jacomo”) was the uncle and godfather of the Dutch artist Jacob de Wit (1695–1754). ↩︎

-

The 1856 Gemäldegalerie catalogue records two paintings by Brueghel with a similar subject: one acquired on behalf of Augustus II by his agent, Raschke, from Jacomo de Wit in Antwerp in 1710 for 300 pistoles, the other bought at the Leipzig Easter Fair in 1722 as a work executed by both Brueghel and Joos de Momper the Younger. The association of the present painting with the Antwerp provenance is confirmed in the 1892 catalogue, which lists the correct dimensions, signature, and date, and makes reference to the original inventory number. See Karl Woermann, Katalog der königlichen Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden: Große Ausgabe, 2nd ed. (Dresden: Bruno Schulze, 1892), 297, no. 888. ↩︎

-

The painting is not listed in the 1765 or 1804 Dresden catalogues, which accords with a note in the 1860 catalogue that the two similar Brueghel paintings (see note 38) were brought to the Dresden Gemäldegalerie in about 1806. See Die Königliche Gemälde-Gallerie im Neuen Museum zu Dresden (Dresden: H. Klemm’s Verlag, 1860), 684 and 690, under nos. 700 and 702. ↩︎

-

Following the abolishment of the monarchy of Saxony after World War I, the collections of the former royal family were placed in the care of the Minister of Culture, who oversaw the newly formed Dresden State Art Collections (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, or SKD). ↩︎

-

As part of a 1919 indemnification agreement with members of the Albertine branch of the House of Wettin, the state granted numerous works of art from the former royal collections to the family. The present painting is included in a subsequent inventory of paintings owned by the House of Wettin (Albertine line) Society (Haus Wettin Albertinischer Linie e.V.). See Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden, Sächsisches Staatsarchiv, 10716 Haus Wettin Albertinischer Linie e.V., Nr. 0303, “Verzeichnis der dem Verein Haus Wettin Albertinischer Linie e. V. gehörigen Bilder. Aufgenommen im August 1928 von Kanzleirat Schubert,” 1928–1941, Cap. IV [Landschaften], no. 143 (as “Niederländischer Kanal mit einem Kirchdorf. Signiert: Brueghel 1612…[Oel a. Holz]…[Grosse {ohne Rahmen)] 0,37 0,615…[Alt Galerie Katalog Nr.] 888”). ↩︎

-

This provenance is listed in Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568–1625): Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde (Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008) 1:247, under cat. 107, and has not been verified. In his unpublished catalogue entry for the painting, Mark Roskill lists “Duke of Sachsen-Meiningen” as its post-Gemäldegalerie provenance but does not specify a date of purchase or location. As the Duchy of Saxe-Meiningen was held by the Ernestine line of the Wettin dynasty, not the Albertine line, it is possible that the painting was subsequently purchased by a member of the Ernestine line, though this has not been confirmed. See Roskill, “Jan Brueghel the Elder, Canal Scene,” in “Clowes Collection Catalogue" (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes archive, around 1968), unpaginated. ↩︎

-

Invoice from Newhouse Galleries to Edith Whitehill Clowes, 5 December 1958, Clowes Registration Archive (C10011), Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎