Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

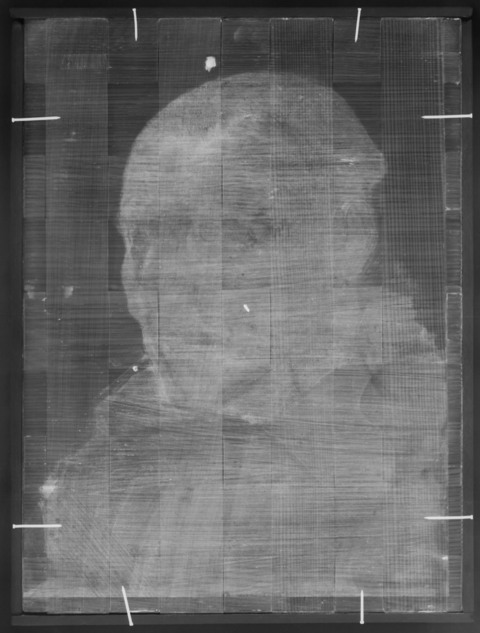

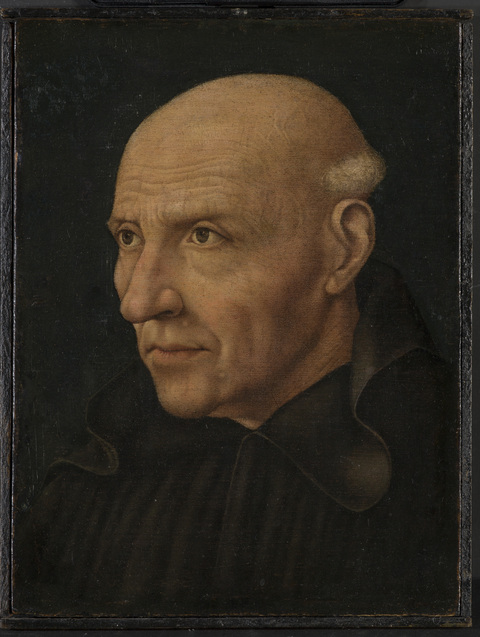

The portrait presents an aged sitter, whose intense gaze focuses on a point outside of the picture space. Wrinkles appearing on his forehead and cheeks are rendered with close attention, capturing the advanced age of the figure. His tonsure identifies him as a monk. His robe appears dark, like the somber background, making his head with its finely painted features stand out. The X-ray reveals

underpainting in lead white, outlining the upper torso and head of the figure, and shows that paint was applied in broad strokes (fig. 1). Upper layers of paint were carefully applied to render facial features. The robe is less detailed, but folds are articulated using black and brown tones to create form.

Figure 1: X-ray image of Unknown artist (possibly French?), Portrait of a Monk, after about 1525, oil on oak panel, 9 × 6-3/4 in. (panel). Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2014.92.

Figure 1: X-ray image of Unknown artist (possibly French?), Portrait of a Monk, after about 1525, oil on oak panel, 9 × 6-3/4 in. (panel). Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2014.92.

The painting’s short recorded history is quite remarkable, not least because it fascinated some of the most eminent scholars of fifteenth-century art at the time this painting resurfaced on the art market. It entered the Clowes Collection sometime in 1958, almost certainly through the auspices of Ivan Podgoursky, who had obtained several written opinions from scholars. The earliest of these was penned by Klaus Perls, who had published a monograph on Fouquet in 1940. Perls compared it to the

Portrait of Guillaume Jouvenel des Ursins (Musée du Louvre, Paris), which he believed to be a work by Jean Fouquet (born about 1415–1420, died before 1481), now confirmed as such and dated to about 1450–1475 (fig. 2).

Walter Friedlaender expressed the same view in 1948, comparing the “ironical expression of the mouth” to the

Portrait of Charles VII (Musée du Louvre, Paris), and to the

Portrait of Étienne Chevalier (Berlin, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin). He added that this painting “considerably enriches our knowledge of the authentic portraits by Fouquet;"

it was thus considered contemporary to key works by Fouquet made during the time of Charles VII (reigned 1422–1461). Yet another expertise was authored by Paul Wescher, former director of Berlin’s Kupferstichkabinett, who fled Germany in 1934 and eventually immigrated to the United States in 1948. Although his expertise is undated, it can be inferred that it was written after he published his 1945 monograph on Fouquet—since he references his monograph in the expertise—and before April 1949, when Podgoursky offered it to Metropolitan Museum of Art benefactor Robert Lehman, who declined it.

Figure 2: Jean Fouquet (French, born about 1415–1420, died before 1481), Portrait of Guillaume Jouvenel des Ursins (1401–1472), Baron de Trainel, Chancellor of France, about 1450–1475, oil on wood, 37-51/64 × 28-47/64 in. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Inv. 9619. Photo: Tony Querrec © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 2: Jean Fouquet (French, born about 1415–1420, died before 1481), Portrait of Guillaume Jouvenel des Ursins (1401–1472), Baron de Trainel, Chancellor of France, about 1450–1475, oil on wood, 37-51/64 × 28-47/64 in. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Inv. 9619. Photo: Tony Querrec © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

The fact that the sitter is looking to the left led A. Ian Fraser, former curator of the Clowes Collection, to speculate that Portrait of a Monk might have been part of a larger ensemble. A fragment depicting the head of a Franciscan friar had been published in 1935 as a newly discovered work by Fouquet, since demoted to an anonymous fifteenth-century portrait, seemed to suggest similarities based on the way the head was proportionally framed. Beyond that, Fraser also saw similarities between the Clowes portrait and Fouquet’s almost life-sized, half-length Portrait of Guillaume Juvenel des Ursins (Musée du Louvre, Paris), in which Guillaume Juvenel, chancellor to King of France Charles VII, is depicted kneeling in prayer in front of elaborate golden pilasters and architraves (see fig. 2). Fraser conjectured that the Clowes portrait might be a portrait of Guillaume’s brother, Jean Jouvenel des Ursins, archbishop of Reims, and possibly part of a triptych featuring both brothers around a central devotional image. However, to this author it seems unlikely that the Clowes portrait relates to the one in the Louvre, since the backgrounds to each figure are quite different. Furthermore, due to the presence of exposed ground only on the left edge of the Clowes painting, there is technical evidence that the panel was not cut down on its left edge.

Directed gazes, and carefully studied, sharp facial features—often with sunken cheeks, wrinkled foreheads, and dominant noses extending beyond the contours of the cheek—have come to define Fouquet’s artistic individuality, and for this reason several scholars came to associate the Clowes portrait with Fouquet rather than with his Flemish contemporaries.

Formally, this author finds the proportions and painted formulation of the wrinkled forehead and tense mouth to be reminiscent of the facial traits present in the portrait of Étienne Chevalier, the left panel of the renowned

Melun Diptych (fig. 3). In that portrait, the face of Étienne Chevalier was reworked at least once during composition planning.

Surface modeling received the same attention as in the Clowes portrait, although there are no apparent similarities in working method or compositional planning between the Melun portrait and the Clowes portrait.

Figure 3: Jean Fouquet (French, born about 1415–1420, died before 1481), Étienne Chevalier with Saint Stephen (left wing of the Melun Diptych, now divided), about 1455, oil on oak, 38-5/32 × 34-23/32 in. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Inv. 1617. Photo Credit: bpk Bildagentur / Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen / Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 3: Jean Fouquet (French, born about 1415–1420, died before 1481), Étienne Chevalier with Saint Stephen (left wing of the Melun Diptych, now divided), about 1455, oil on oak, 38-5/32 × 34-23/32 in. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Inv. 1617. Photo Credit: bpk Bildagentur / Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen / Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY.

The main figure of the Clowes portrait is painted on a single oak board with the wood grain running horizontally, contrary to the convention typically observed in portraits produced in France and the Netherlands in the fifteenth century. Its small format might suggest that it could have been a fragment cut from a larger composition, except on its left edge, as mentioned previously. In addition to its illusive original size, technical analysis of this painting is further complicated by evidence of severely abraded areas in the thin paint film of the dark greenish-blue background beyond the figure. Modern pigments, like zinc and titanium, are present there, indicating that extensive restoration has been done.

Of critical significance regarding a putative attribution to Fouquet, however, was a second dendrochronological examination done in 2019 in conjunction with the production of this digital catalogue, which determined a later tree ring result, resulting in a creation date of after about 1525, and therefore beyond Fouquet’s lifetime. By the first half of the sixteenth century, the portrait culture of the French court had returned to small-scale portraiture codified in the earlier workshops of Corneille de Lyon and in that of the brothers Jean and François Clouet. The painting’s reduced format may also suggest that the painter of this portrait may have worked from a drawing to capture the sitter’s likeness, as was often the case in other portraits from the period. No such drawing has yet been identified, but perhaps future research will allow such a connection to be made.

Author

Christine Seidel

Provenance

Probably New York art market by 1946;

Ivan N. Podgoursky, New York or Boston, by 1948 or possibly slightly earlier;

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1958;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2014, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10040);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2014 (2014.92).

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 25, as French School, Portrait of a Monk;

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 18, as Portrait of a Monk;

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, 1963, Northern European Painting—The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 1;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection as unknown artist (possibly French), Portrait of a Man.

References

David G. Carter, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), no. 25 (reproduced);

John Howett, A Lenten Exhibition Loaned by the Clowes Fund, Incorporated of Indianapolis, exh. cat. (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, 1962), no. 18;

Henry R. Hope, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, exh. cat. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Art Museum, 1963), no. 1;

Mark Roskill, "Clowes Collection Catalogue" (unpublished manuscript), 1968, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art;

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 140, as Portrait of Jean Juvenal des Ursins II (?) (reproduced).

Notes