Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

In fifteenth-century Venice, wealthy patrons seeking devotional images of the Madonna often turned to Giovanni Bellini (1431/1436–1516), the foremost painter in the city, whose variations on the Marian theme were especially noteworthy. Building on the tradition of Byzantine icons, and expanding on the formal innovations of his father Jacopo (about 1400–1470/1471), Bellini and his workshop produced images of the Madonna and Child that, in turn, exerted their influence long after the artist’s death. Bellini’s trademark, established in more than eighty variants of the Marian theme, retained the solemnity and iconography of Byzantine examples, while offering depictions of great immediacy and intimacy. Madonna and Child, attributed to Bellini’s workshop, reflects his signature style and provides insight into the workings of his prestigious and dynamic bottega.

Seated in half-length and three-quarter view in the ambiguous space between the parapet, in the foreground, and a crimson cloth of honor, in the middle ground, the Madonna gazes down at her son, who reclines in her lap. He, in turn, gazes upward, with his mouth slightly open and his left hand touching his chin. His right hand rests above his knee, with his thumb and two fingers extended in a gesture that seems to be both a vestige of a former Byzantine blessing and a subtle reminder of the dual nature of the Christ child as both human and divine.

Dominating the picture plane, the monumental figures draw the viewer into a realm that is both temporal and otherworldly. Mary is dressed in traditionally symbolic garb, an earthly red tunic and a celestial blue robe. Her head covering and gold-trimmed mantle recall that of the Virgin Mary shown in the traditional Byzantine icons that made their way to Italy after the Sack of Constantinople in 1204. In Bellini’s representations, these references to Mary’s exalted status are counterbalanced by allusions to her maternal humanity. As intermediary to Christ, she holds her son reverently before the worshiper with expressive hand positions that emphasize his preciousness. Symbolically, she is the corporeal monstrance, assuming the role of sacred vessel for the protection and display of the Blessed Sacrament. The majestic, haloed Christ child of Byzantine icons has been replaced by the curly headed, rosy-cheeked Child, so often seen in works by Bellini. He is depicted in his full humanity, naked and vulnerable in the lap of his mother. Both mother and son are fully present in their earthly weightiness, the solid forms of their bodies betrayed by the shadows that they cast.

In its original domestic context, a devotional image such as this granted the worshiper a private audience with the holy pair. The consequential size and static postures of the figures encouraged sustained contemplation and veneration, and emphasized their intimate presence and connection to the viewer. Although the parapet acts as a visual and metaphorical barrier, restricting full access to the Virgin and Child, the distant landscape reminds the viewer of the earthly plane, of Christ’s ultimate sacrifice and the resulting privilege bestowed upon mankind when He came to earth as the Godhead in human form.

By 1480, Giovanni Bellini was head of the largest workshop in Venice, meeting the demand for devotional images and altarpieces, and continuing work on a commission to paint the cycle of canvases for the Doge’s Palace begun by his brother Gentile (about 1429–1507). Although no primary documents relating to Bellini’s workshop activity exist, analysis of the paintings can help shed light on the dynamic and flexible conventions that allowed for replication while ensuring, to some degree, the stamp of the master. Emerging from this context, the Clowes Madonna and Child stands as an illustrative example of a devotional image executed by workshop hands according to the traditional working procedures established by Giovanni Bellini.

Among the many innovative designs produced by Bellini and his shop, that of the Clowes

Madonna and Child must have been one of the most marketable, given the number of times it was replicated both within the workshop and beyond.

Three versions most relevant to the Clowes painting are in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City (fig. 1);

the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, DC (fig. 2);

and a panel ascribed to Pasqualino Veneto (active from 1496–died 1504), formerly in the Goudstikker collection (fig. 3).

Figure 1: Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1485, oil on canvas, transferred from wood panel, 28-9/16 × 21-13/16 in. Photo: Jamison Miller. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, F61-66.

Figure 1: Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1485, oil on canvas, transferred from wood panel, 28-9/16 × 21-13/16 in. Photo: Jamison Miller. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, F61-66.

Figure 2: Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child in a Landscape, about 1490–1500, oil on panel, 29-3/16 × 22-15/16 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.262.

Figure 2: Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child in a Landscape, about 1490–1500, oil on panel, 29-3/16 × 22-15/16 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.262.

Figure 3: Pasqualino Veneziano (Italian, 1463–1504), The Madonna and Child, about 1490–1495, oil and tempera on panel, 31-1/4 × 24-1/2 in. Private Collection of Jacques Goudstikker, Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images.

Figure 3: Pasqualino Veneziano (Italian, 1463–1504), The Madonna and Child, about 1490–1495, oil and tempera on panel, 31-1/4 × 24-1/2 in. Private Collection of Jacques Goudstikker, Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images.

The known versions of the Clowes composition have been a part of art historical scholarship since the painting’s first mention in 1930 by Georg Gronau. Listing the work as an autograph version by Bellini, Gronau considered it to be the model for the Washington painting. His view that the Clowes painting was a precursor to other versions was followed in 1948 by Erica Tietze-Conrat, who, believing it to be by Bellini, suggested that it was the earliest of the known versions because of the archaic use of a background curtain rather than a continuous landscape, as seen in the Kansas City and Washington versions. Fourteen years later, Fritz Heinemann, in his exhaustive catalogue of paintings by Bellini and his followers, listed it among several other versions and considered it to be in the manner of Vincenzo di Biagio Catena (1470–1531). Later, in a volume published posthumously in 1991, he revised his attribution, listing the painting as “probably by the hand of Bartolomeo Veneto." The attribution to Veneto (active 1502–died 1531) was reiterated in 1997 by Laura Pagnotta in her monograph on that artist.

The current attribution to Bellini’s workshop is based, in part, on the presence of shared formal elements made popular by the Venetian master. Comparison of the Clowes

Madonna and Child to autograph works of Giovanni Bellini reveal their commonalities. In figure types and composition, the Clowes

Madonna and Child can be compared to the

Madonna of Alzano (Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) (fig. 4) and the

Madonna and Child with Red Cherubs (Venice, Galleria dell’Accademia) (fig. 5), both of which feature an ample and wide-eyed Christ child, seated on the Madonna’s draped knee, looking up with an enigmatic expression. In type, the Madonnas of Bergamo and Venice correspond closely to the Clowes version, with their broad cheeks, rounded jawlines, small lips, and heavy-lidded eyes. They also share the open-mouthed, curly haired Christ child with full cheeks and pronounced chin. However, the greater naturalism evident in the more secure works gives way, in the Clowes version, to a rigidity and awkwardness that certainly points to a workshop assistant.

Figure 4: Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child (Madonna of Alzano), about 1485–1487, oil on panel, 33-3/16 × 25-25/32 in. Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo, inv. 58MR00020.

Figure 4: Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child (Madonna of Alzano), about 1485–1487, oil on panel, 33-3/16 × 25-25/32 in. Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo, inv. 58MR00020.

Figure 5: Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child with Red Cherubs, about 1480–1490, oil on wood, 30-5/16 × 23-5/8 in. Photo: Scala/Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY. Galleria dell’Accademia, Venice, Inv. 612.

Figure 5: Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child with Red Cherubs, about 1480–1490, oil on wood, 30-5/16 × 23-5/8 in. Photo: Scala/Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY. Galleria dell’Accademia, Venice, Inv. 612.

Adding to these associations with autograph works is the Clowes panel’s close relationship to the versions in Washington and Kansas City, both of which can be attributed to Bellini’s workshop with greater certainty. Comparison of the paint surfaces of the latter two examples shows that they share all primary contours, presupposing the use of a workshop cartoon in their creation. Conversely, the dimensions of the Clowes Madonna are smaller. The Nelson-Atkins version, which is generally considered to be the finest in the series, was transferred to canvas sometime between 1929 and 1951. Unfortunately, this procedure has made a proper assessment of the painting’s underdrawing impossible. Such a loss of technical information is unfortunate, as it may have shed light on how the Kansas City painting was made and the role it played in the creation of other versions. The compromised condition and stylistic inconsistencies of the Nelson-Atkins painting, and the subsequent difficulty in determining its authorship, have made scholars hesitant to deem it a prototype. Instead, all the extant versions, including the Clowes painting, may have been based on a lost Bellini original.

A special connection can be made between the Clowes painting and the one in the National Gallery of Art, as it seems likely that the artist of the Clowes panel had access either to the Washington painting or a drawing made from it. A comparison between the underdrawing and the painted surface of the Washington panel illustrates that the artist changed the drapery folds above the Madonna’s proper right eye from the underdrawing phase to the paint stage. This detail provides an important clue to determining the sequence of the two versions. Both the underdrawing and the paint surface of the Clowes painting follow the drapery change made in the paint stage of the National Gallery of Art painting, indicating that the Washington painting may have served as inspiration for the Clowes version.

Contrasting what has been referred to as the “workmanlike” style of the painted surface,

the extensive underdrawing of the Clowes

Madonna and Child betrays the hand of a thinking artist, who, rather than mechanically copying a design, carefully worked through the composition with considerations of form, light, and shadow. The underdrawing can be characterized by a variety of styles that delineate and model the forms of the figures. The outlines of the figures were drawn first, with a certainty that points to the use of a cartoon. Areas of shadow were then indicated with

hatching. Some of the hatching carefully and delicately follows the forms, as can be seen in the face and proper right hand of the Madonna (fig. 6) and the face, neck, and chest of the Child. In other areas, the artist has reinforced the primary outline with a bolder and more generally applied hatching. This can be seen in the proper right forearm, lower back, and buttocks of the Child, and the hand of the Virgin that supports the Child from below (fig. 7). Here the parallel strokes are applied broadly, in some cases over the contour lines, in a medium that appears fluid. In other areas, such as the Child’s lower torso and proper left forearm, cross-hatching is created with a subsequent application of diagonal, parallel marks. Incision lines can also be identified, in both raking light and in the X-radiograph, along the chest and stomach of the baby’s left side, along the top of the left leg and under the calf and part of the thigh, and along the central contour of the Virgin’s blue mantle. The function of these incisions is unclear, although their presence along several of the major compositional contours may point to the design

transfer technique known as

calcare, in which a sharp stylus is used to incise the lines of a cartoon directly onto the prepared surface of a panel.

Figure 6: Infrared reflectogram; detail of Virgin’s proper right hand. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–1515, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342.

Figure 6: Infrared reflectogram; detail of Virgin’s proper right hand. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–1515, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342.

Figure 7: Infrared reflectogram; detail of Virgin’s proper left hand. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–1515, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342.

Figure 7: Infrared reflectogram; detail of Virgin’s proper left hand. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–1515, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342.

A comparison of the Clowes painting’s underdrawing and paint surface shows that the artist followed the underdrawing closely with only a few minor changes to the contours on the paint surface. These alterations include adjustments to the size and the general outline of the Child’s feet, the bottom contour of the lower hand of the Virgin, the contour of the Child’s back, and the chin and side of the Virgin’s face (fig. 8).

Figure 8: Infrared reflectogram assembly. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–15, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342..

Figure 8: Infrared reflectogram assembly. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–15, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342..

In the past three decades, insight into Bellini’s graphic style has been greatly aided by infrared reflectography (IRR) examinations carried out in connection with conservation treatments of his paintings. Prior to the examinations that document the underdrawings of more than two dozen paintings attributed to Giovanni Bellini and his workshop, understanding of the artist’s graphic style was based on drawings on paper that could not be attributed to Bellini’s hand with certainty. The recent technical studies reveal even greater evidence of the Venetian artist’s technical versatility. Echoing the artist’s eclectic painting style, his underdrawing style ranged from highly finished and refined hatched drawings to simple outlines without any indication of modeling or elaboration of details. The underdrawing for the Clowes Madonna and Child has something in common with other underdrawings found in paintings attributed to Bellini and his workshop. The delicate and regular parallel hatching that is used to indicate the shadows of the faces of both the Madonna and Child in the Clowes painting is similar to underdrawing found in Madonna and Child Between Two Saints (Venice, Galleria dell’Accademia). In this comparative example, the composition was transferred by way of a cartoon and subsequently shaded through careful parallel hatching. The more fluid and spontaneous underdrawing that can be seen in the torso of the Child and the proper right hand of the Madonna is more akin to the underdrawing of the Dead Christ Held by Two Angels (Venice, Museo Civico Correr). There the broad liquid contours and hatching are applied in a deliberate but free manner.

What is revealed in the technical studies of Bellini’s paintings is a fluid and flexible approach to art production, one that employed a host of varying techniques that were responsive to the needs of the artists and patrons alike. That Bellini’s inventions and methods escaped the boundaries of his own workshop is evidenced by an untold number of compositional borrowings, both direct and indirect, by independent artists working outside the Bellini

bottega. A perfect example of this is the signed painting by Pasqualino Veneto (fig. 3), which replicates the dimensions and contours of the Kansas City and Washington paintings almost exactly. The presence of

spolveri in IRR indicates that its design was transferred by way of a pricked cartoon. Careful hatching of the forms to indicate areas of shadow, even under the gilded robe of the Madonna, suggests that the artist was working from a fully hatched drawing.

The practice of modeling an underdrawn compositional design that has been mechanically transferred to a support is consistent with the evidence also found in the Clowes

Madonna and Child and underscores the diversity of underdrawing techniques used by the Bellini workshop, even within the same work. It suggests that even though mechanical methods of transfer were employed for the sake of efficiency, in the case of the Clowes Madonna, the creative process is still very much apparent.

Figure 3: Pasqualino Veneziano (Italian, 1463–1504), The Madonna and Child, about 1490-95, oil and tempera on panel, 31-1/4 × 24-1/2 in. Private Collection of Jacques Goudstikker, Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images.

Figure 3: Pasqualino Veneziano (Italian, 1463–1504), The Madonna and Child, about 1490-95, oil and tempera on panel, 31-1/4 × 24-1/2 in. Private Collection of Jacques Goudstikker, Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images.

At least in the genre of devotional images, market demand necessitated streamlined procedures that ensured both stylistic homogeneity as well as efficient workshop production. The transfer of popular designs by way of a cartoon, whether pounced or traced, was carried out by master and pupil alike as an effective means of expediting the preparatory process. As more technical studies are being conducted on the paintings of Bellini and his workshop, the versatility and adaptability of the artist’s working methods are becoming better known. The Clowes Madonna and Child serves as a useful case study to this end.

Author

Andrea Golden

Provenance

Count Alessandro Contini-Bonacossi (1878–1955), Rome and Florence;

Jules S. Bache (1861–1944), New York, in 1928;

Sale at (Kende Galleries at Gimbel Brothers, New York) in 1945;

purchased by (E & A. Silbermann Galleries, New York);

George H. A. Clowes (1877–1958), Indianapolis, in 1945;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2000, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10005);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2000 (2000.342).

Exhibitions

Newark Museum, NJ, 1940, Masterpieces of Art: European Paintings from the New York and San Francisco World’s Fairs 1939, no. 7;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 5;

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 4;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1962, Italian and Spanish Painting from the Clowes Collection, no. 17.

References

Baron D. von Handeln, Zeitschrift für Bildender Kunst 21 (1909–1910), 139;

Georg Gronau, Klassiker der Kunst: Giovanni Bellini (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1930), 127–128, 212;

Raimond Van Marle, The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 17 (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1935), 292, 294;

Masterpieces of Art: European Paintings from the New York and San Francisco World’s Fairs 1939; Catalog of the Exhibition, the Newark Museum, October 1 Through October 27, 1940, exh. cat. (Newark: Newark Museum, 1940), 7;

Erica Tietze-Conrat, "An Unpublished Madonna by Giovanni Bellini and the Problem of Replicas in His Shop," Gazette des Beaux-Arts (June 1948): 379–382 (reproduced);

Fritz Heinemann, Giovanni Bellini e i Belliniani, vol. 1 (Venice: Neri Pozza, 1962), 13f (reproduced);

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973),14;

Fern Rusk Shapley, Catalogue of the Italian Paintings, 2 vols. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1979), 1:55–56;

Fritz Heinemann, Giovanni Bellini e i Belliniani, vol. 3, Supplemento e ampliamenti (Hildesheim, Zurich, and New York: Olms Verlag, 1991), 6 (reproduced);

Eliot Wooldridge Rowlands, The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), 117–124 (reproduced);

Laura Pagnotta, Bartolomeo Veneto: L’opera completa (Florence: Centro Di, 1997), 293–94.

Ronda Kasl, ed., Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 90–151 (reproduced).

Technical Notes and Condition

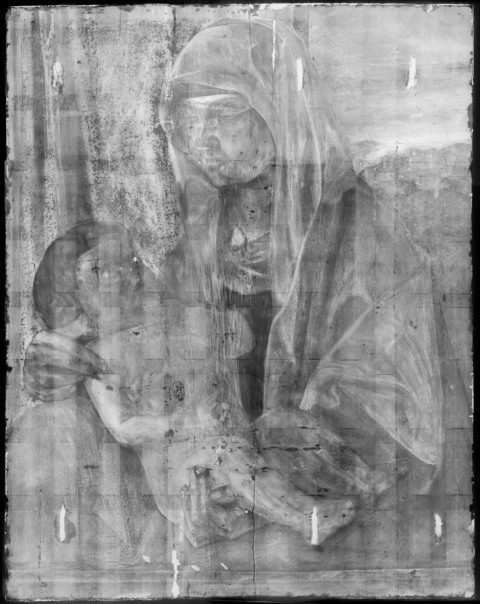

The painting’s support consists of a single poplar panel that has been thinned and cradled. Washboarding and splitting along the vertical cradle members is particularly evident in raking light and is undoubtedly due to the immobility of the cradle. Extensive worm tunneling is also apparent. In some cases, the tunneling has been filled with a wax-resin. This same wax-resin was used to fill six large holes, three along the top and three along the bottom of the panel (fig. 9).

Figure 9: X-radiograph. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–15, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342.

Figure 9: X-radiograph. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–15, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342.

Other notable losses can be identified at the Madonna’s collarbone, above and including some of the white fabric at her neck, and in the center of the Child’s body above his proper right wrist. Smaller losses can be seen throughout the panel (fig. 10). In particular, the areas of red, including both the curtain and the Virgin’s red garment, have suffered from a large amount of paint loss (fig. 9).

Figure 10: Ultraviolet (visible) fluorescence photograph. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–15, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342.

Figure 10: Ultraviolet (visible) fluorescence photograph. Workshop of Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436–1516), Madonna and Child, about 1510–15, tempera and oil on wood, 21 × 16-1/2 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.342.

The discernible techniques employed by the artist of the Bellini workshop Madonna and Child, as revealed through a multitude of scientific methods of investigation, is consistent with numerous other works that issued from the master’s shop. The ground was applied in two layers, the gesso grosso and the gesso sottile of which Cennino Cennini speaks, and is made of gypsum and animal glue, with an additional topcoat of animal glue. In less dense areas of the X-ray film, a fine weavelike pattern can be detected that might point to the use of fabric on the panel prior to the application of gesso. If fabric does, in fact, exist, it would seem that it was applied only to a few small areas rather than to the entire panel. The pattern can only be seen in a few areas of the X-ray and there is no evidence of the presence of fabric in any of the paint samples.

Notes