Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

Author

Provenance

Sir Richard Levinge (1911–1984), Knockdrin Castle, Ireland;16

to (C. Marshall Spink, London), probably via (Adolf Fritz Mondschein, Vienna) in 1939.17

(E. and A. Silberman, New York);18

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1941;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2014, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10006);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2014.

Exhibitions

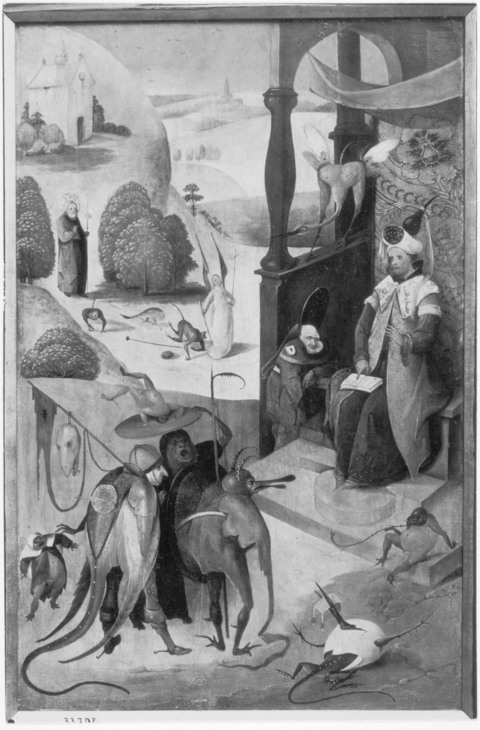

World’s Fair, New York, Masterpieces of Art, 1939;

Detroit Institute of Arts, Masterpieces of Art from European and American Collections: European Paintings from the Two World’s Fair of 1939, no. 3;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1950, Holbein and His Contemporaries, no. 7;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 6;

Musée Communal des Beaux-Arts, Bruges, 1960, Le Siècle des Primitifs Flamands, no. 66;

Detroit Institute of Arts, 1960, Masterpieces of Flemish Art: Jan van Eyck to Bosch, no. 56 (catalogue titled Flanders in the Fifteenth Century);

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 6;

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, 1963, Northern European Painting—The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 18.

References

Otto Benesch, “Ein Spätwerk von Hieronymus Bosch,” In Mélanges Hulin de Loo, 36–44. Brussels: Librairie Nationale d'Art et d'Histoire, 1931;

E.P. Richardson, “Augmented Return Engagement and Positive Farewell Appearance of the Masterpieces of Art from Two World’s Fairs,” Art News 40, no. 6 (1941): 17;

Jacques Combe, Jerome Bosch (New York: Universe Books, 1957);

Ludwig von Baldass, Hieronymus Bosch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1960);

Detroit Institute of Arts, Flanders in the Fifteenth Century, exh. cat. (Detroit, 1960), 208–210;

Charles de Tolnay, “The Paintings of Hieronymus Bosch in the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” Art International 7, no. 4 (1963): 27;

Charles de Tolnay, Hieronymus Bosch (New York: Reynal and Company, 1966), 352;

Jheronimus Bosch: Exhibition Noordbrabants Museum, ’s-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands, 17 Sept.–15. Nov. 1967, exh. cat. (’s-Hertogenbosch: Hieronymus Bosch Exhibition Foundation, 1967), 101;

Karl Arndt, “Zur Ausstellung ‘Jheronimus Bosch,'” Kunstchronik 21 (1968): 19;

Brigitte Völker, “Die Entwicklung des Erzählenden Halbfigurenbildes in der Niederländischen Malerei des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts,” PhD diss., Universität Göttingen,1968, 96;

Max J. Friedländer, Early Netherlandish Painting: Geertgen tot Sint Jans and Jerome Bosch (Leiden: Sijthoff, 1969).

Mia Cinotti, The Complete Paintings of Bosch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1971), 98, no. 27;

Carl Linfert, Hieronymus Bosch, trans. Robert Erich Wolf (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1971);

John G. Johnson Collection: Catalogue of Flemish and Dutch Paintings (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1972), 7–8;

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 104–5;

Gert Unverfehrt, Hieronymus Bosch: Die Rezeption seiner Kunst im frühen 16. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Mann, 1980), 129n457, 133, 243, no. 9, pl. 80;

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, Handbook of European and American Paintings to 1945. (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1981);

Kathleen Dardes and Andrea Rothe, The Structural Conservation of Panel Paintings: Proceedings of a Symposium at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 24–28 April 1995 (Malibu: Getty Publications, 1998), 46;

Peter Klein, “Dendrochronological Analysis of Works by Hieronymus Bosch and His Followers,” in Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights into His Life and Work, ed. Jos Koldeweij and Bernard Vermet (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2001), 125;

Frédérique Elsig, Jheronimus Bosch: La question de la chronologie (Geneva: Droz, 2004), 142.

Notes

-

Peter Parshall, “Penitence and Pentimenti: Hieronymus Bosch’s Mocking of Christ in London,” in Tributes in Honor of James H. Marrow: Studies in Painting and Manuscript Illumination of the Late Middle Ages and Northern Renaissance, ed. Anne S. Kortweg (London: Harvey Miller, 2006), 378. ↩︎

-

Charles de Tolnay, “The Paintings of Hieronymus Bosch in the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” Art International 7, no. 4 (1963): 27; See also John G. Johnson Collection: Catalogue of Flemish and Dutch Paintings (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1972), 8. This catalogue also mentions that the IMA painting was likely to be in the hands of a London restorer, C. Marshall Spink, who corresponded with the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1937–38 and purchased photos of the Johnson panel before the 1938 cleaning. The correspondence, kindly provided by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, does not reveal how these photos were consulted. ↩︎

-

Hanns Swarzenski, “An Unknown Bosch,” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston 53, no. 291 (1955): 5. See also Ludwig von Baldass, Hieronymus Bosch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1960), 236. William Breazeale, Cara Denison, Stacey Sell, and Freyda Spira, A Pioneering Collection: Master Drawings from the Crocker Art Museum (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2010), see https://www.crockerart.org/collections/works-on-paper/artworks/christ-carrying-the-cross). ↩︎

-

Charles de Tolnay, “The Painting of Hieronymus Bosch in the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” Art International 7, no. 4 (1963): 27. ↩︎

-

Charles de Tolnay, Hieronymus Bosch (New York: Reynal & Company, 1966), 352.

Mia Cinotti, The Complete Paintings of Bosch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1971), 98. ↩︎

-

Mia Cinotti, The Complete Paintings of Bosch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1971), 98. ↩︎

-

Charles de Tolnay, joining a group of early and midcentury art historians, attributes the Johnson Ecce Homo to Bosch. Otto Benesch places it to the end of Bosch’s youthful period, while Tolnay, Jacques Combe, and Carl Linfert assign it to his early maturity. Reluctant to accept the attribution, Ludwig van Baldass, sees it a youthful work. Karl Arndt refutes the attribution altogether. See Mia Cinotti, The Complete Paintings of Bosch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1971), 98; Max J. Friedländer, Early Netherlandish Painting: Geertgen tot Sint Jans and Jerome Bosch (Leiden: Sijthoff, 1969), 83, no. 78; Otto Benesch, “Ein Spätwerk von Hieronymus Bosch,” in Mélanges Hulin de Loo (Brussels: Librairie Nationale d'Art et d'Histoire, 1931), 36–44; Jacques Combe, Jerome Bosch (New York: Universe Books, 1957), 27; Carl Linfert, Hieronymus Bosch, trans. Robert Erich Wolf (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1971), 70; Ludwig von Baldass, Hieronymus Bosch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1960), 236; Karl Arndt, “Zur Ausstellung ‘Jheronimus Bosch,'” Kunstchronik 21 (1968): 19. Regarding the Clowes panel, Wilhelm Valentiner regards it an “excellent characteristic work of Jerome Bosch,” while Hans Tietze sees it a superior copy in terms of coloring and details. See Wilhelm Valentiner’s 1940 expertise and the letter dating 25 February 1941 from Abris Silberman to G.H.A. Clowes. File C10006, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

See the report on the dendrochronological analysis carried out in 1994 by Peter Klein. File C10006, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. See also Peter Klein, “Dendrochronological Analysis of Works by Hieronymus Bosch and His Followers,” in Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights into His Life and Work, ed. Jos Koldeweij and Bernard Vermet (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2001), 125. ↩︎

-

P. Gerlach, “De ‘Temptatie van St. Antonius’ te Antwerpen afkomstig uit ’s-Hertogenbosch,” Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen (1968): 76–77. See also Jacques Combe, Jerome Bosch (New York: Universe Books, 1957), 67n72; Gert Unverfehrt, Hieronymus Bosch: Die Rezeption seiner Kunst im frühen 16. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Mann, 1980), 133. ↩︎

-

I thank Lawrence Lipnik for identifying the wind instrument in the Garden of Earthly Delights. ↩︎

-

Frédérique Elsig, Jheronimus Bosch: La question de la chronologie (Geneva: Droz, 2004), 142. ↩︎

-

P. Gerlach, “De ‘Temptatie van St. Antonius’ te Antwerpen afkomstig uit ’s-Hertogenbosch,” Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen (1968): 77. ↩︎

-

RKD Kunstwerknummer 60914. ↩︎

-

RKD Kunstwerknummer 56524 & 56525. ↩︎

-

Frédérique Elsig, Jheronimus Bosch: La question de la chronologie (Geneva: Droz, 2004), 141. ↩︎

-

Correspondence between Spink and Clowes indicates that the painting was obtained from Sir Richard Levinge, see Letters, 6 April 1956 and 15 February 1957, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. In the latter, the restorer Spink relates that he had contacted Levinge to learn the identity of the previous owner of the painting, but Levinge reported that he had no old records. ↩︎

-

A photograph of the Clowes painting bears a Friedländer notation on the back that reads: “Spink London/ d.[urch]Mondschein/VI.39;” see Annotation to Illustration number 111685, Friedländer Project, Rijksbureau voor kunsthistorisches Documentatie (RKD), The Hague. It is possible that Spink had business connections during this period with Adolf Fritz Mondschein, later known as Frederick Mont, after Mont’s immigration to the US in 1939. ↩︎

-

Letter from Abris Silberman to G.H.A. Clowes, 24 February 1941, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎