Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

5That which Hieronymus Bosch did with wisdom and decorum others did, and still do, without any discretion and good judgment; for having seen in Flanders how well received was this kind of painting by Hieronymus Bosch, they decided to imitate it and painted monsters and various imaginary subjects, thus giving to understand that in this alone consisted the imitation of Bosch. In this way came into being countless numbers of paintings of this kind which are signed with the name of Hieronymus Bosch but are in fact fraudulently inscribed: pictures to which he would never have thought of putting his hand but which are in reality the work of smoke and the short-sighted fools who smoked them in fireplaces in order to lend them credibility and an aged look.3

Author

Provenance

Gustav von Gerhardt (1848–1911), Budapest, until 1911.24

Mrs. Moric Palugyay (née Olga Gerhardt?) and Mrs. Moric Tomcsanyi, née Margit Gerhardt (1879–1944), Budapest, by 1927.25

Ivan N. Podgoursky (1901–1962), New York;

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1944;26

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2020, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10007);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2020.

Exhibitions

Mucsarnok [Hall of Exhibitions], Budapest, 1927, L’Exposition Belge: Ancien et Moderne, no. 191;

Denver Art Museum, Chapell House, 1947, Art of the United Nations, no. 97;

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA, 1954, Shadow and Substance: The Art Film and Its Sources, no. 7;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 7;

Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 7;

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, IN, 1963, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 19;

Denver Art Museum, 1966, Great Stories in Art, reproduced in leaflet;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at the Newfields, Indianapolis, 2017–2018, On the Flip Side: Secrets on the Backs of Paintings;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at the Newfields, Indianapolis, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection.

References

Sammlung des. Königl[ichen]. Ungar[ischen]. Hofrats Gustav von Gerhardt, Budapest: Zweiter Teil; Gemälde Alter Meister, sale cat. (Berlin: Rudolph Lepke’s Kunst-Auctions-Haus, 10 November 1911), no. 61, pl. 30;

Catalogue de l’Exposition Belge d’art Ancien et Moderne (Budapest: Imp. de la Société Anonyme Athenaeum, 1927), 34, no. 191;

Max J. Friedländer, Early Netherlandish Painting: Geertgen tot Sint Jans and Jerome Bosch

(Leiden: Sijthoff, 1969), 86, no. 90 (wrong measurements);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 106–107 (reproduced);

Gerd Unverfehrt, Hieronymus Bosch: Die Rezeption seiner Kunst im frühen 16. Jahrhundert

(Berlin: Mann, 1980), 273, nos. 89c–k;

Molly A. Faries et al., “The Recently Discovered Underdrawings of the Master of the Saint Ursula Legend’s Triptych of the Nativity,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 62, no. 4 (1987): 19n16;

Molly A. Faries and J.R.J. van Asperen de Boer, “Covering-over or Covering-up: Some Instances

of Re-use of Panels in Painting after Hieronymus Bosch,” in Le Dessin Sous-jacent et la

Technologie dans le Peinture, Colloque XI, 14–16 Septembre 1995: Dessin Sous-jacent et

Technologie de la Peinture; Perspectives, Louvain-la-Neuve 1997 (Louvain: Collège Érasme,

1997), 15–16, pl. 5;

Peter Klein, “Dendrochronological Analysis of Works by Hieronymus Bosch and His Followers,”

in Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights into His Life and Work, ed. Jos Koldeweij and Bernard Vermet (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2001) 128;

Peter van den Brink, “The Art of Copying: Copying and Serial Production of Paintings in the Low

Countries in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries,” in Bruegel Enterprises, ed. Peter

van den Brink (Maastricht: Bonnefantenmuseum, 2002), 38;

Peter van den Brink, “Hieronymus Bosch as Model Provider for a Copyright Free Market,” in

Jérôme Bosch et son entourage et autres études: Colloque XIV 13–15 Septembre 2001, Bruges–

Rotterdam (Louvain and Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2003), 86–87, figs. 1–2;

Molly A. Faries, “Making and Marketing: Studies of the Painting Process,” in Making and Marketing: Studies of the Painting Process in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish Workshops, ed. Molly A. Faries (Turnhout: Brepols, 2006), 7–9, figs. 2–3;

Stephan Kemperdick, “Kopien, Varianten, Reminiszenzen, Vervielfältigungen von Bosch,” in Hieronymus Bosch und seine Bildwelt im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, exh. cat. (Berlin: Gemäldegalerie und Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen, 2016), 19.

Notes

-

For example, whereas the Lisbon central panel shows an armored cavalry troop marching over a bridge in the upper register, the Clowes painting depicts one soldier on a horse. ↩︎

-

See Nicole N. Conti, “Hieronymus Bosch’s Lisbon Temptation of St. Anthony: Parameters for Patronage,” Dutch Crossing 35, no. 3 (2011): 286–294. ↩︎

-

For Guevara’s text, see Wolfgang Stechow, Northern Renaissance Art, 1400–1600: Sources and Documents in the History of Art, ed. H. W. Janson (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1966), 19. See also Larry Silver, Peasant Scenes and Landscapes: The Rise of Pictorial Genres in the Antwerp Art Market (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 134. For a discussion on Guevara’s opinion and Bosch’s reception in Spain from 1560 to 1800, see Helmut Heidenreich, “Hieronymus Bosch in Some Literary Contexts,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 33 (1970): 171–199. ↩︎

-

Stephan Kemperdick, “Kopien, Varianten, Reminiszenzen. Vervielfältigungen von Bosch,” in Hieronymus Bosch und seine Bildwelt im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2016), 19. ↩︎

-

Bertram Lorenz, “Triptychon der Versuchung des Hl. Antonius (Kopie nach Hieronymus Bosch, um 1560/70),” in Hieronymus Bosch und seine Bildwelt im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2016), 102. ↩︎

-

Stephan Kemperdick, “Kopien, Varianten, Reminiszenzen. Vervielfältigungen von Bosch,” in Hieronymus Bosch und seine Bildwelt im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2016), 19. ↩︎

-

Stephan Kemperdick, “Kopien, Varianten, Reminiszenzen. Vervielfältigungen von Bosch,” in Hieronymus Bosch und seine Bildwelt im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2016), 19; Peter van den Brink, “Hieronymus Bosch as Model Provider for a Copyright Free Market,” in Jérôme Bosch et son entourage et autres études: Colloque XIV 13–15 Septembre 2001, Bruges–Rotterdam (Louvain and Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2003), 91. ↩︎

-

See Erma Hermens and Greta Koppel, “Copying for the Art Market in 16th-Century Antwerp: A Tale of Bosch and Bruegel,” in On the Trail of Bosch and Bruegel: Four Paintings United under Cross-Examination, ed. Erma Hermens (London: Archetype Publications, 2012) 81–95; Peter van den Brink, “Hieronymus Bosch as Model Provider for a Copyright Free Market,” in Jérôme Bosch et son entourage et autres études: Colloque XIV 13–15 Septembre 2001, Bruges–Rotterdam (Louvain and Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2003), 84–101; and Larry Silver, “Second Bosch: Family Resemblance and the Marketing of Art,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 50 (1999): 30–56. ↩︎

-

See Dan Ewing, “Marketing Art in Antwerp, 1460–1560: Our Lady’s Pand,” The Art Bulletin 72, no. 4 (990): 558–584. ↩︎

-

Larry Silver, “Second Bosch: Family Resemblance and the Marketing of Art,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 50 (1999): 39. ↩︎

-

The triptych, or the “tabla con dos pares,” as the inventory describes it, was suggested to have possibly been the Lisbon original by Ludwig von Baldass. See Ludwig von Baldass, Hieronymus Bosch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1960), 232. Paul Vandenbroeck opines that the triptych is a copy. The wings may be Prado no. 2050 and no. 2051; see Paul Vandenbroeck, “The Spanish inventories reales and Hieronymus Bosch,” in Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights into His Life and Work, ed. Jos Koldeweij et al. (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2001), 51n13. The two single panels are referred to as “tabla de pintura.” Only one of these “tabla” is said to depict the “Tentación de sant Antón.” The other simply depicts “Sant Antón.” see Paul Vandenbroeck, “The Spanish inventories reales and Hieronymus Bosch,” in Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights into His Life and Work, ed. Jos Koldeweij et al. (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2001), 50–52. ↩︎

-

The terms used for describing the paintings in the 1614 inventory are “tabla pintada al olio,” “lienço pintado al temple,” and “lienço pintado al fresco.” See Paul Vandenbroeck, “The Spanish inventories reales and Hieronymus Bosch,” in Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights into His Life and Work, ed. Jos Koldeweij et al. (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2001), 55–57. Argote de Molina, a sixteenth-century chronicler, mentioned that there were seven Temptations of St. Anthony in El Pardo before 1582. This account, however, does not match what the inventories reveal. See Pilar Silva Maroto, “Bosch in Spain: On the Works Recorded in the Royal Inventories,” in Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights into His Life and Work, ed. Jos Koldeweij et al. (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2001), 42. ↩︎

-

The terms used to describe these paintings are “pintura al temple,” “pintura al olio,” lienço al temple," and “pintura sobre tabla.” See Paul Vandenbroeck, “The Spanish inventories reales and Hieronymus Bosch,” in Hieronymus Bosch: New Insights into His Life and Work, ed. Jos Koldeweij et al. (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, 2001), 58–60. ↩︎

-

Peter van den Brink, “Hieronymus Bosch as Model Provider for a Copyright Free Market,” in Jérôme Bosch et son entourage et autres études: Colloque XIV 13–15 Septembre 2001, Bruges–Rotterdam (Louvain and Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2003), 84. ↩︎

-

Molly A. Faries, “Making and Marketing: Studies of the Painting Process,” in Making and Marketing: Studies of the Painting Process in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish Workshops, ed. M. A. Faries (Turnhout: Brepols, 2006), 8. ↩︎

-

Peter van den Brink, “Hieronymus Bosch as Model Provider for a Copyright Free Market,” in Jérôme Bosch et son entourage et autres études: Colloque XIV 13–15 Septembre 2001, Bruges–Rotterdam (Louvain and Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2003), 84. ↩︎

-

See, for example, Joos van Cleve’s Self Portrait (about 1519, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, no. 1930.128) and Jan Gossaert’s Portrait of a Merchant (about 1530, National Gallery of Art, no. 1967.4.1). ↩︎

-

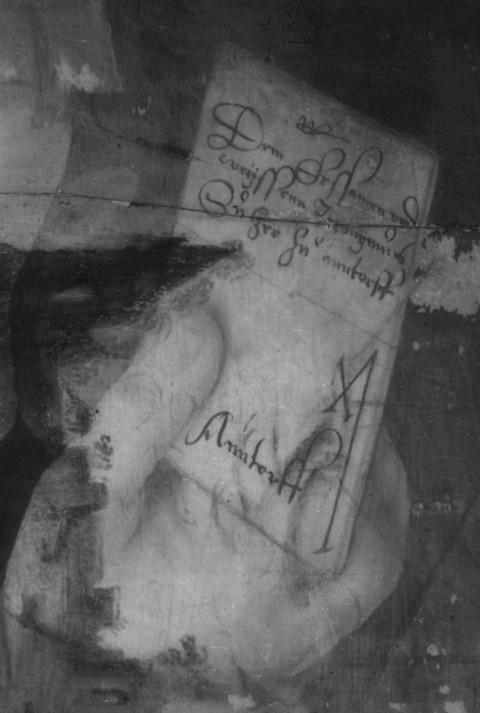

Transcribed in Molly A. Faries and J.R.J. van Asperen de Boer, “Covering-over or

Covering-up: Some Instances of Re-use of Panels in Painting after Hieronymus Bosch,” in Le

Dessin Sous-jacent et la Technologie dans le Peinture, Colloque XI, 14–16 Septembre 1995:

Dessin Sous-jacent et Technologie de la Peinture; Perspectives, Louvain-la-Neuve 1997 (Louvain:

Collège Érasme, 1997), 16. In 2019 Marc Smith, professor of paleography, École nationale des Chartes, interpreted the text with the following minor modifications: Dem Erssamen und / weijssenn Ieronymus/ Sulzer Zu anntorff / Anntorff. ↩︎

-

The trademark appears on the back of the letter, which would have been folded, perhaps more than once, to conceal the inside that would have contained the date and place of writing. ↩︎

-

See P. Grun, “Die Sulzer in Augsburg,” Heraldisch-genealogische Blätter für adelige und bürgerliche Geschlechter (1905): 41–42. ↩︎

-

Jacob Strieder, Aus Antwerpener notariatsarchiven: Quellen zur deutschen Wirtschaftsgeschichte des 16. Jahrhunderts (Wiesbaden: F. Steiner, 1962), 168ff. See also correspondence between Mark Häberlein, professor of History, University of Bamberg, and Annette Schlagenhauff, curator of European art, August 2016, File C10007, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

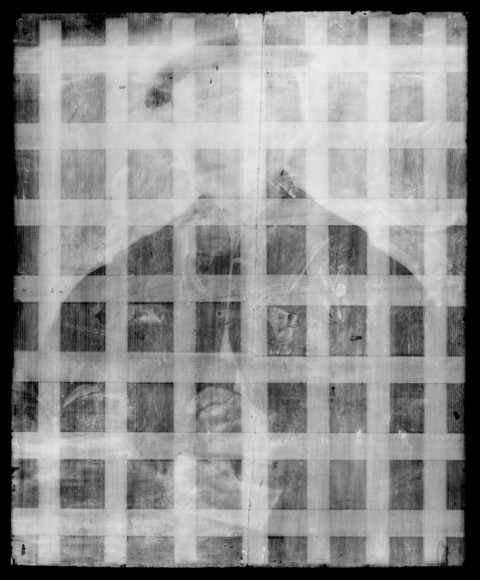

The underlying portrait was discovered by Martin Radecki, former chief conservator of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, in 1974. ↩︎

-

Pigment analysis was carried out in 1974 at the Intermuseum Laboratory in Oberlin, Ohio. It has been confirmed that, because of the painting’s use of lead tin yellow, it must predate 1750, when use of the pigment was abandoned. The pigment was not rediscovered until 1942. Peter Klein, who performed a dendrochronological analysis of the Clowes painting in 1994, suggests that the painting would have been created from 1531 onward. This suggestion corresponds well with the underlying portrait, which represents fashion of the early sixteenth century. ↩︎

-

Sammlung des. Königl[ichen]. Ungar[ischen]. Hofrats Gustav von Gerhardt, Budapest: Zweiter Teil : Gemälde Alter Meister, sale cat., Rudolph Lepke’s Kunst-Auctions-Haus, Berlin, 10 November 1911, no. 61 (plate 30). ↩︎

-

Catalogue de l’Exposition Belge d’art Ancien et Moderne (Budapest: Imp. de la Société Athenaeum, 1927), 34, no. 191. This can only be explained if the painting was bought in at the 1911 Berlin auction, because both Gerhardt’s daughters are given as owners in the 1927 exhibition catalogue. ↩︎

-

Statement by Podgoursky (indicating that G.H.A. Clowes purchased this painting in December 1944), undated 1945, Correspondence files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. About ten years later, in 1954, Clowes noted that he had just learned from Podgoursky that this painting was “originally owned by a collector named Goodstecher, of Amsterdam”; letter from Clowes to Bartlett H. Hayes, 22 February 1954, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. This could be a reference to Jacques Goudstikker, whose gallery stock was looted by the Nazis in July 1940. A search of the LostArt.de database for items still missing from the family of the renowned art dealer Goudstikker does not list a painting with the subject “The Temptation of St. Anthony” by either Bosch or a follower. Nor does such a painting appear in Goudstikker’s “Black Book” available on the website of the Jewish Museum in New York at https://s3.amazonaws.com/tjmassets/exhibition_pdfs/Akte-38-Blackbook.pdf (accessed 27 April 2022).

Jan Thomas Köhler, of the Goudstikker Art Research Project, has confirmed that Goudstikker owned another version of Temptation of St Anthony with smaller dimensions (50 x 39 .5 cm); see Catalogue collection Goudstikker: 10e exposition dans les locaux de “Pulchri Studio," exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Goudstikker, 1926), no. 9 (reproduced). Jan Thomas Köhler, email message to Annette Schlagenhauff, 28 April 2022. This version is now in the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, No. 2441 (OK).

It should, furthermore, be noted that Podgoursky was not a reliable source for information. ↩︎