Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

At top of cross: INRI

Bottom center: 1532, flanking serpent holding a ring in its mouth with open wings, facing right

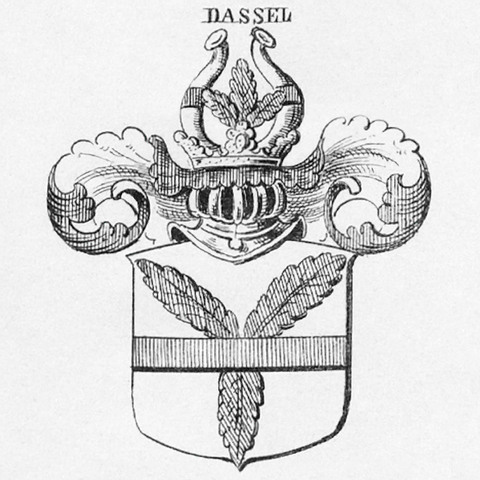

Bottom center: coat of arms of the Dassel family

Bottom left: GENEROSO DNO HENRICO RANTZOVIO VICARIO REGIS DANIAE /

PRODUCI CIMBRICO D.D. HARDWIGVS A DASSEL IC.CAESAR.

XXVI DIE OCTOBRIS. ANNO CD.D.XCVI

[Given to the Honorable Henry Rantzau, Vicary of the King of Denmark, Nobleman of Holstein, by Doctor Hardwig of Dassel, in the Emperor’s Service, on the 26th day of October, 1596]

Entry

Author

Provenance

Hardwigus a Dassel, Doctor of the Canonic and Civil Law (1557–1608), member of Dassel family, near Einbeck, Hannover, by 1596;13

Heinrich Rantzau (1526–1598), probably Schloss Breitenburg, near Itzehoe, Schleswig-Holstein.14

Antonia Migazzy, née Marczibanyi (died 1886);15

Possibly Prince Windisch-Graetz, Sarospatak, Hungary or possibly Count Hans Johann Nepomuk Wilczek (1837–1922), Kreuzenstein Castle;16

(E. and A. Silberman, New York);

Dr. G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1936;17

Clowes Fund Collection, Indianapolis, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10030);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2000.

Exhibitions

Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, 1936, The Centennial Exposition: Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Arts, no. 15 (illustrated);

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1950, Holbein and His Contemporaries, no. 19;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 20;

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 13;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1963, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 42.

References

Daniel Catton Rich, Catalogue of the Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection of Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1938), 39, no. 34;

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), xlvii–xlviii, 176–177;

Max J. Friedländer and Jakob Rosenberg, The Paintings of Lucas Cranach (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1978), 112, no. 218;

Anthony F. Janson, 100 Masterpieces of Painting (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 50–53;

Laurinda S. Dixon, “The Crucifixion by Lucas Cranach the Elder: A Study in Lutheran Reform Iconography,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 35–42;

Ellen Wardwell Lee, ed., Indianapolis Museum of Art Highlights of the Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2005), 96;

Martha Wolff, ed., Northern European and Spanish Paintings before 1600 in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Collection (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), 356;

Crucifixion, US_IMA_2000-344, In Cranach Digital Archive, http://www.lucascranach.org/digitalarchive.php.

Notes

-

The absence of an inscription makes the identification ambiguous. The Centurion is often accompanied by the inscription, “Truly this man was the Son of God!” (Mark 15:39). Longinus is the name given to the soldier who pierced Christ’s side with a spear (John 19:34–35); he is sometimes shown pointing to his eye, a reference to a miraculous cure. The two figures are often confused.

I am extremely grateful to the staff of the National Gallery of Art library for their unfailing and cheerful assistance. A note of thanks also to Gunnar Heydenreich of the Cranach Digital Archive for his expertise and help. ↩︎

-

Anthony F. Janson, 100 Masterpieces of Painting (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 52; and Laurinda S. Dixon, “The Crucifixion by Lucas Cranach the Elder: A Study in Lutheran Reform Iconography,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 38, fig. 10. ↩︎

-

Ruth Mellinkoff, Outcasts: Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993). ↩︎

-

The literature on the Reformation and on Lutheranism and the visual arts is enormous. See, however, Bonnie-Jeanne Noble, “The Lutheran Paintings of the Cranach workshop 1529–1555,” PhD diss., Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 1998; Carl C. Christensen, Art and the Reformation in Germany (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1979); and Sonja Poppe, Bibel und Bild: Die Cranachschule als Malwerkstatt der Reformation (Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2014). ↩︎

-

Laurinda S. Dixon, “The Crucifixion by Lucas Cranach the Elder: A Study in Lutheran Reform Iconography,” Perceptions 1 (1981): 37–39. ↩︎

-

Martha Wolff, Northern European and Spanish Paintings before 1600 in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Collection (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), 356. ↩︎

-

Martha Wolff, Northern European and Spanish Paintings before 1600 in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Collection (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), 353–358. ↩︎

-

Stephan Klingen, Die deutschen Gemälde des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts: Anhaltische Gemäldegalerie Dessau (Weimar: Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1996), 32, 34, no. 16. See also Max J. Friedländer and Jakob Rosenberg, The Paintings of Lucas Cranach (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1978), 144, no. 377. ↩︎

-

Gunnar Heydenreich, Report, 24 July 2002 (2 pages), available at Cranach Digital Archive, https://lucascranach.org/documents/US_IMA_2000-344_FR218/09_Other/US_IMA_2000-344_FR218_2002_Document-001.pdf and https://lucascranach.org/documents/US_IMA_2000-344_FR218/09_Other/US_IMA_2000-344_FR218_2002_Document-002.pdf. ↩︎

-

John Oliver Hand, with the assistance of Sally E. Mansfield, German Paintings of the Fifteenth through Seventeenth Centuries (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993), 26. ↩︎

-

The painting measures 76 × 55 cm and is signed with the winged serpent. This is the painting that is mistakenly reproduced in Max J. Friedländer and Jakob Rosenberg, The Paintings of Lucas Cranach (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1978), 112, no. 218. Prior to being acquired, the picture was auctioned in Cologne, Lempertz, 21–25 November 1957, no. 448, lot 30, and Vienna, Dorotheum, 9 October 1996, lot 175. The absence of the inscription at the lower left implies, but does not prove, that the copy was made before the inscription was added in 1596 at the earliest. ↩︎

-

In much of Northern Europe, artistic production was regulated by the guilds, which set standards of quality and membership. Only artists who were certified as masters by the guild could sell their work. Assistants lived in the master’s studio for several years learning all aspects of production, and they could obtain guild membership as independent artists. Journeymen were not guild members but were artists who could be hired on a temporary basis; they had to learn to quickly emulate the style of the head of the workshop. They were especially useful in the event of a large commission with a pressing deadline. ↩︎

-

Based on the inscription on the painting at bottom left, which reads in translation, “Given to the Honorable Heinrich Rantzau, Vicary of the King of Denmark, nobleman of Holstein by Doctor of the Canonic and Civil Law Hardwigus of Dassel, in the Emperor’s service on the 26th day of October 1596.” Also known as Hartwig von Dassel. His identity as a member of the Dassel family is confirmed by the Dassel coat of arms at the bottom center of the painting. A brief biography can be found in Steffenhagen, “Dassel, Hartwig von,” in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 4 (1876), 761, https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd122855345.html#adbcontent. ↩︎

-

Based on the inscription on the painting at bottom left, which reads in translation, “Given to the Honorable Heinrich Rantzau, Vicary of the King of Denmark, nobleman of Holstein by Doctor of the Canonic and Civil Law Hardwigus of Dassel, in the Emperor’s service on the 26th day of October 1596.” A brief biography can be found in Gottfried Heinrich Handelmann, “Rantzau, Heinrich,” in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 27 (1888), 278–279, https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd11898716X.html#adbcontent. ↩︎

-

A paper label on the back of the panel reads “Gróf Migazzy Antónia,” a probable reference to Countess Antonia Migazzy. ↩︎

-

Ownership by Windischgraetz, or Windisch-Graetz, was suggested by the art historian William E. Suida; see Suida to G.H.A. Clowes, 22 January 1949, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. This has not been corroborated. Wilczek’s name is not mentioned by Silberman as a previous owner. This may be because Silberman never wanted to reveal his immediate sources. Alternatively, speculation at a later date may be the reason his name is linked with this painting. Wilczek is known to have had an Old Master collection, but it is uncertain whether the Crucifixion owned by Clowes comes from the Wilczek collection. For more on Wilczek, see Andreas Nierhaus, Kreuzenstein: Die mittelalterliche Burg als Konstruktion der Moderne (Vienna, Cologne, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag, 2014), 67–78. ↩︎

-

Purchase agreement between G.H.A. Clowes and Abris Silberman, 2 January 1936, Clowes Registration Archive, Correspondence Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎