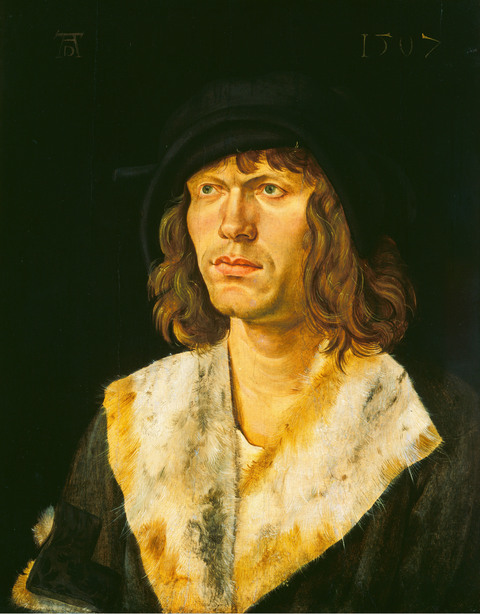

Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

Inscribed at top, upper left: 1504

Inscribed at top, upper right: ALT 25

Pale yellow monogram “A” on the sitter’s shirt

Entry

Author

Provenance

Probably Count Móric Sándor (1805–1878), Budapest;

Probably to his daughter, Pauline Metternich, Vienna.20

(E. and A. Silberman Galleries, Vienna and New York);21

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1935;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2004, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10032);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2004 (2004.159).

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1950, Holbein and His Contemporaries, no. 24;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 22;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1963, Northern European Painting:The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 41;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection;

Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, China; Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha, China; Chengdu Museum; 2020–2021, Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting.

References

Gustav Glück, “Ein neu gefundenes Gemälde Albrecht Dürers,” Belvedere: Illustrierte Zeitschrift für Kunstammler 12 (1934/1936): 117–119 (reproduced);

Hans Tietze, Meisterwerke europäischer Malerei in Amerika (Vienna: Phaidon, 1936), 202, 338–339 (reproduced);

Hans Tietze and Erika Tietze-Conrat, Kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke Albrecht Dürers: Der Reife Dürer (Augsburg: B. Filser, 1937–1938), 77–78, 217;

Erwin Panofsky, Albrecht Dürer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1943), 19;

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

Angela Ottino Della Chiesa, Tout l’œuvre peint de Dürer (Paris: Flammarion, 1969), no. 108;

Dieter Koepplin and Tilman Falk, Lukas Cranach: Gemälde, Zeichnungen, Druckgraphik; Ausstellung im Kunstmuseum Basel (Basel and Stuttgart: Birkhäuser, 1976), 673–675 (reproduced);

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, 100 Masterpieces of Painting: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 54–55 (reproduced);

Jeffrey Chipps Smith, Nuremberg: A Renaissance City, 1500–1618 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983), 140 (reproduced);

Kurt Löcher, Hans Schäufelein: Vorträge, Gehalten anlässlich des Nördlinger Symposiums im Rahmen der 7. Rieser Kulturtage in der Zeit vom 14. Mai bis 15. Mai 1988 (Nördlingen: Verein Rieser Kulturtage, 1990), 116–117 (reproduced);

Christof Metzger, Hans Schäufelin als Maler (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 2002), 217–219 (reproduced);

Sebastian Schmidt, Abbild/Selbstbild: Das Porträt in Nürnberg um 1500 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2018), 252–253 (reproduced);

Dieter Wuttke, “Von der Person zur Genealogie: Neues zum Nürnberger Humanisten und Inhaber Städtischer Ämter Pangratz Schwenter d. Ä,” Jahrbuch für fränkische Landesforschung 75 (2015): 76–80 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen et al., Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 132–133 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen et al., Floating Lights and Shadows: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 130–131 (reproduced).

Technical Notes and Condition

The original wood panel has been thinned to approximately 1 millimeter in depth and is adhered to a solid composite/compressed wood board backed with vertically grained veneer and a seven-member wood cradle. The panel’s original verso and edges were planed, leveled, and smoothed in preparation for the addition of the secondary support components. This structural intervention was most likely completed in the early 1930s, prior to the sale of the painting to George H.A. Clowes. The original wood plank shows extreme deterioration and damage, while the auxiliary support system offers a secure and planar support for the rigid paint layer. X-radiographs reveal wood splints filling two splits along the conjunctions of the original planks and at the central crack. What remains of the original panel appears too degraded and thin to independently support the picture layer, and the painting relies on the strength provided by the layered auxiliary support.

The panel appears to have been prepared for painting with a thin layer of glue-based off-white ground that would have likely been applied by a brush and then scraped to achieve a smooth and level surface free of texture. A warm-toned imprimatura appears to cover the entire picture plane, and prominent horizontal brushwork visible through abraded paint layers indicates that it was applied with a coarse bristled brush. The ground is extremely thin, allowing the texture of the wood grain to remain visible under specular and raking illumination.

The preliminary stage in the creation of this painting includes the execution of an underdrawing using a plant-based charcoal medium. Close examination of the sitter’s chin shows that its shape was slightly altered and extended in the painted layers from cleft to square; the black paint of the sitter’s cloak appears in the originally established contour of the chin. The painting is heavily overpainted, and differences between pigments applied by artist and restorer are difficult to discern. Nonetheless, the artist appears to have used a limited color palette consisting of red, yellow, white, black, blue, and brown. The use of blue to accent the jewel in the sitter’s ring is possible, yet multiple applications of overpaint have obscured the original material.

Microscopic islands of red paint throughout the background indicate that the portrait background was at one time overpainted in red. The very red paint extends over edges of the figure and is present in age cracks and old losses, indicating its use a later alteration. (A treatment record detailing the paint removal has not been preserved.) On the abraded surface are multiple campaigns of overpaint, some of which match well with surrounding colors, while others have discolored. Although the paint layer has sustained extensive damage, cohesion between and within layers appears secure. Horizontal striations in the sitter’s face appear to result from exposed imprimatura, which shows through abraded paint.

Notes

-

Erwin Panofsky, Albrecht Dürer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1943), 19. ↩︎

-

Kurt Löcher, Hans Schäufelein: Vorträge, Gehalten anlässlich des Nördlinger Symposiums im Rahmen der 7. Rieser Kulturtage in der Zeit vom 14. Mai bis 15. Mai 1988 (Nördlingen: Verein Rieser Kulturtage, 1990), 116; Christof Metzger, Hans Schäufelin als Maler (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 2002), 218. ↩︎

-

See Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, 100 Masterpieces of Painting: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 54. ↩︎

-

“Die vornehme Haltung, der lebendige, etwas nachdenkliche Ausdruck der Augen, der Schwung der Umrißlinien im Kopf und in der Gewandung, die sorgfätige [sorgfältige?], aber nirgends kleinliche malerisches Behandlung sind von einer überwältigenden Große des stils und der Auffassung und lassen nur an einen Künstler höchsten Ranges denken. Betrachtet man die Einzelheiten, so wird einem die Urheberschauft Albrecht Dürers völlig deutlich.” Gustav Glück, “Ein neu gefundenes Gemälde Albrecht Dürers,” Belvedere; Illustrierte Zeitschrift für Kunstammler 12 (1934/1936): 118. ↩︎

-

From William Suida’s note, File 2004.159 (C10032), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Hans Tietze and Erika Tietze-Conrat, Kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke Albrecht Dürers: Der Reife Dürer (Augsburg: B. Filser, 1937–38), 77–78, 217. ↩︎

-

Erwin Panofsky, Albrecht Dürer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1943), 19. ↩︎

-

Kurt Löcher, Hans Schäufelein: Vorträge, Gehalten anlässlich des Nördlinger Symposiums im Rahmen der 7. Rieser Kulturtage in der Zeit vom 14. Mai bis 15. Mai 1988 (Nördlingen: Verein Rieser Kulturtage, 1990), 118. ↩︎

-

See Barbara Butts, s.v. “Schäufelein: (I) Hans Schäufelein the Elder,” The Dictionary of Art, vol. 28 (1996), 57–60. ↩︎

-

Barbara Butts, s.v. “Schäufelein: (I) Hans Schäufelein the Elder,” The Dictionary of Art, vol. 28 (1996), 57–60; John Oliver Hand and Sally E. Mansfield, German Paintings of the Fifteenth through Seventeenth Centuries (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993), 160. ↩︎

-

The Washington Portrait of a Man was accepted as a work of Dürer by Friedrich Winkler in 1928, although most contemporaneous art historians believed differently. The Warsaw Portrait of a Man, too, was first given to Dürer before the Muzeum Narodowe attributed it to Schäufelein in 1951. See John Oliver Hand and Sally E. Mansfield, German Paintings of the Fifteenth through Seventeenth Centuries (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993), 160–165. ↩︎

-

See Wilhelm Suida’s expertise from 1935 and a biography of Christopher Scheurl the Younger, likely provided by Suida, File 2004.159 (C10032), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. In a later, undated, note, Suida corrects himself, suggesting that the sitter’s age is 25, not 23. Suida’s note, File 2004.159 (C10032), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Dieter Wuttke, “Von der Person zur Genealogie: Neues zum Nürnberger Humanisten und Inhaber Städtischer Ämter Pangratz Schwenter d. Ä,” Jahrbuch für fränkische Landesforschung 75 (2015): 76–80. ↩︎

-

See Shira Brisman, “Sternkraut: ‘The Word that Unlocks’ Dürer’s Self-Portrait of 1493,” in The Early Dürer, ed. Daniel Hess and Thomas Eser (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2012), 194–196. ↩︎

-

See Shira Brisman, “Sternkraut: ‘The Word that Unlocks’ Dürer’s Self-Portrait of 1493,” in The Early Dürer, ed. Daniel Hess and Thomas Eser (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2012), 195. ↩︎

-

This is Joseph Leo Koerner’s translation. Joseph Leo Koerner, The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993), 31. ↩︎

-

Such understanding is shared by a number of scholars, including Gustav Glück, Erwin Panofsky, Kurt Löcher, and Jeffrey Chipps Smith. ↩︎

-

Shira Brisman, “Sternkraut: ‘The Word that Unlocks’ Dürer’s Self-Portrait of 1493,” in The Early Dürer, ed. Daniel Hess and Thomas Eser (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2012), 204. ↩︎

-

Shira Brisman, “Sternkraut: ‘The Word that Unlocks’ Dürer’s Self-Portrait of 1493,” in The Early Dürer, ed. Daniel Hess and Thomas Eser (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2012), 201. ↩︎

-

This Austro-Hungarian provenance is recorded in a letter from William E. Suida to G.H.A. Clowes, 22 January 1949, Suida correspondence, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Sales agreement between Silberman Galleries and G.H.A. Clowes, 18 April 1935, File 2004.159 (C10032), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. This portrait was then attributed to Dürer. ↩︎