Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

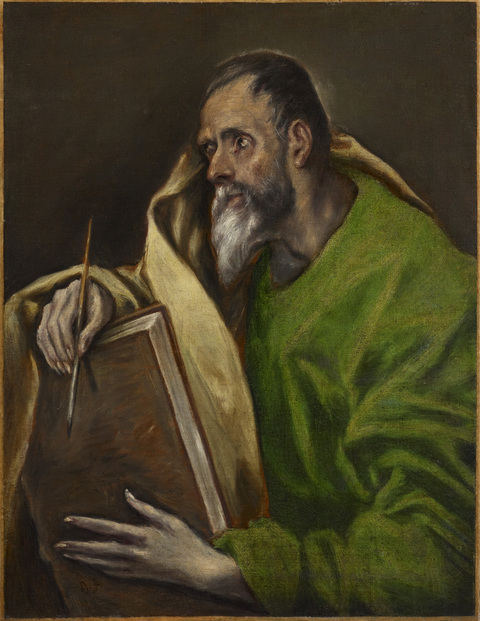

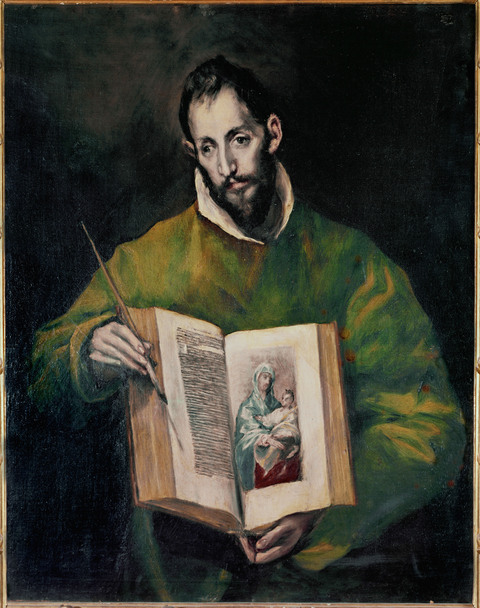

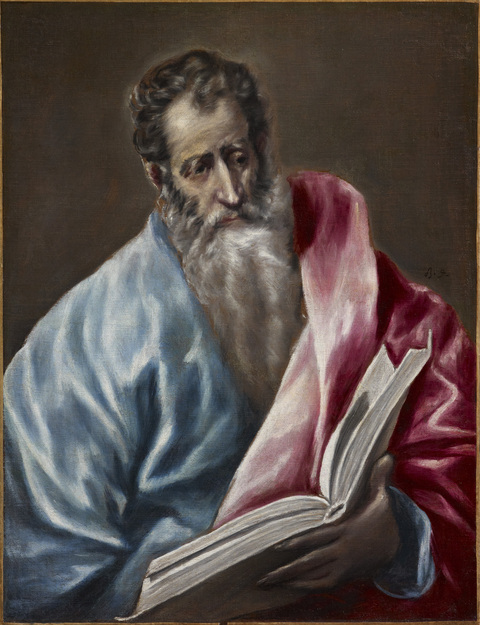

Initials “δθ” by proper left hand of the sitter (2008.273)

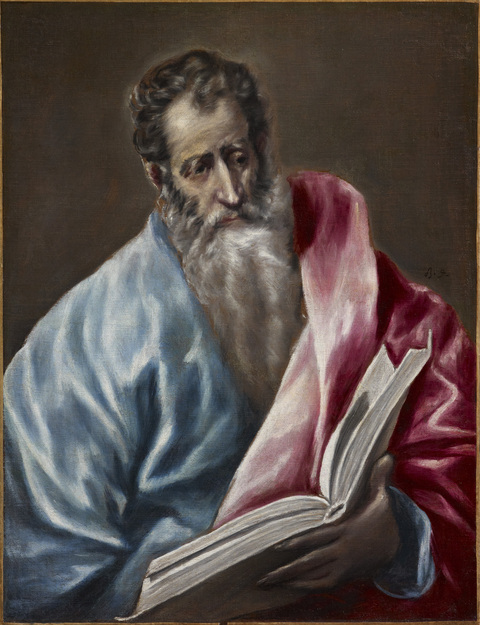

Initials “δθ” in background above proper left shoulder (2007.53)

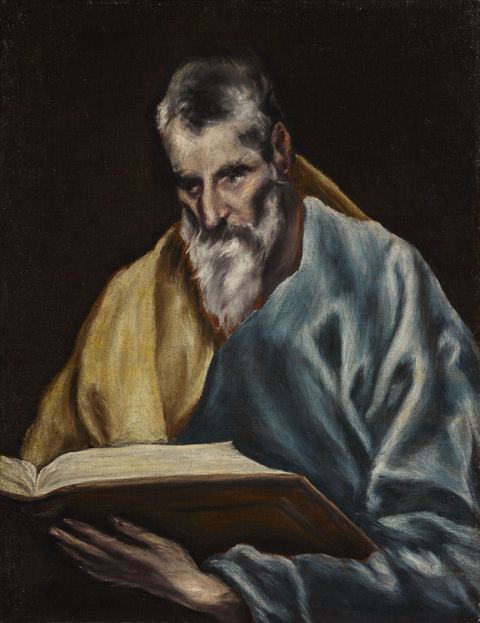

Initials in background near proper left shoulder (2008.274)

Entry

Author

Provenance

Parish church of Almadrones, Guadalajara, Spain, until 1936 or shortly thereafter;16

removed to the Fuerte of Guadalajara (former convent of San Francisco), until 1941;17

at the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, for conservation treatment, 1941–1945;

restituted to the bishopric of Sigüenza in 1945, sold and legally exported in 1952;18

(Newhouse Galleries, Inc. New York);

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1952;19

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2007/8, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10034, C10035, C10036);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2007–2008.

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, IN, 1954, Pontormo to Greco, nos. 67, 65, and 66;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, IN, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 34; no. 32; no. 33;

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, nos. 25, 23, and 24;

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, IN, 1962, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, nos. 29, 27, and 28;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, IN, and Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI, 1963, El Greco to Goya, nos. 24, 22, and 23;

Museo de Santa Cruz, Toledo, 2014, El Greco, arte y oficio, nos. 71, 72, 73;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection;

Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, China; Hunan Museum, Changsha, China; Chengdu Museum; 2020–2021, Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting.

References

Enrique Lafuente, “El Greco: Some Recent Discoveries,” The Burlington Magazine 87, no. 513 (1945): 299;

J. Camón Aznar, Dominico Greco (Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 1950), 2:1072, no. 289; 981; 1053; 1372; no. 291; 1053; 1372; no. 293;

Harold E. Wethey, El Greco y su Escuela (Madrid: Ediciones Guadarrama, 1967), 2: no. 190; no. 191 (reproduced); no. 193;

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 50, 52, 54 (reproduced);

Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, Benito Navarrete, and Rafael Alonso, El Greco, Apostolados (La Coruña: Fundación Barrié de la Maza, 2002), 25; 115; 128; 129; 130 (reproduced, the numbers 2008.274, St. Simon, and 2007.53, St. Matthew, are reversed);

Sarah Schroth, “Retratando a los apóstoles: Notas sobre el Apostolado de El Greco en el Museo del Prado,” El Greco (Barcelona: Galaxia-Circulo de Lectores 2003), 383n6;

Leticia Ruiz Gómez, El Greco en el Museo Nacional del Prado: Catálogo razonado (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2007), 151, 152 (reproduced);

Leticia Ruiz Gómez et al., El Greco, arte y oficio, exh. cat. (Toledo: Museo de Santa Cruz, 2014), 80–81 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen, et al., Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 46–47 (St. Matthew, reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen, et al., Floating Lights and Shadows: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 46–47 (St. Matthew, reproduced).

Notes

-

El Greco’s Apostolados have been analyzed by Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, Benito Navarrete, and Rafael Alonso, El Greco, Apostolados (La Coruña: Fundación Barrié de la Maza), 2002 and Fernando Marías and María Cruz de Carlos Varona, El Greco: Los Apóstoles, Santos y “Locos de Dios” (Toledo: Fundación El Greco 2014, 2010). More recently, Leticia Ruiz in El Greco, arte y oficio, exh. cat. (Toledo: Museo de Santa Cruz, 2014). ↩︎

-

According to the report of the Marqués de Lozoya, Director General de Bellas Artes from 1939–1951: “El Sr. Comandante del “Fuerte de Guadalajara” halló en los desvanes del mismo nueve lienzos enrrollados, los que fueron toscamente restaurados por un sargento aficionado a la pintura, y después se colocaron en un sitio alto y muy poco visible.” See “Expediente de restauración de nueve lienzos del Greco (apostolado) propiedad de la Agrupación de Ingenieros de Guadalajara,” 10 September 1941, Archivo del Museo del Prado. ↩︎

-

The Museo Nacional del Prado keeps the following paintings: Savior, St. James, St. Thomas, and St. Paul. The painting at the LACMA is St. Andrew, and St. John the Evangelist is at the Schorr Collection, UK. ↩︎

-

See Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art. ↩︎

-

Letter from Newhouse to G.H.A. Clowes, 9 June 1952, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art. ↩︎

-

Letter from Newhouse to G.H.A. Clowes, 1 April 1952, Correspondence, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art. Nevertheless, Newhouse sold the St. John the Evangelist (nowadays in the Schorr collection) to the Kimbell Art Foundation in 1949 according to David M. Robb, Kimbell Art Museum: Catalogue of the Collection (Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum, 1972), 44. ↩︎

-

Letter from Edward O. Korany to Bertram Newhouse, 20 December 1952, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor to G.H.A. Clowes, 21 November 1952, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Harold E. Wethey, El Greco y su Escuela, 2 vols. (Madrid, Ediciones Guadarrama, 1967), 2:121. ↩︎

-

El Greco, arte y oficio, exh. cat. (Toledo: Museo de Santa Cruz, 2014), 76. ↩︎

-

See María Cruz de Carlos Varona, “Speculum Pastorum: Los Apóstoles del Greco y la iglesia toledana de comienzos del Seiscientos,” in El Greco: Los Apóstoles, Santos y “Locos de Dios,” ed. Fernando Marías and María Cruz de Carlos Varona (Toledo: Fundación El Greco 2014, 2010), 64–68 for images of the paintings, stretchers, and inscriptions. ↩︎

-

María del Carmen Garrido Pérez and Jaime García-Máiquez, El Greco pintor: Estudio técnico (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2015), 399. ↩︎

-

“El non finito permite comprobar cómo esbozaba sus ideas a través de brochas muy diferentes de manera directa y rápida, sobre un fondo de imprimación rojizo anaranjado oscuro, destacando las zonas de luces por medio de fuertes golpes de materia pictórica, con alto contenido en albayalde, que restriega con gruesos pinceles por la superficie y que difumina y matiza con pinceles muy finos o de pelo más suave en otras. También se observa que el pintor determinaba normalmente desde el principio lo que iba a quedar en sombra y los acabados finales, sobre todo en los rostros.” María del Carmen Garrido Pérez and Jaime García-Máiquez, El Greco pintor: Estudio técnico (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2015), 399. ↩︎

-

María del Carmen Garrido Pérez and Jaime García-Máiquez, El Greco pintor: Estudio técnico (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2015), 423, fig. 33.36. ↩︎

-

For this interpretation, see María Cruz de Carlos Varona, “Speculum Pastorum: Los Apóstoles del Greco y la iglesia toledana de comienzos del Seiscientos,” in El Greco: Los Apóstoles, Santos y “Locos de Dios,” ed. Fernando Marías and María Cruz de Carlos Varona (Toledo: Fundación El Greco 2014, 2010), 53–83. ↩︎

-

Eyewitness accounts confirm that prior to the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), these paintings, along with others from the same series, were in the parish church of Almadrones, in the province of Guadalajara. Hispanist Harold Wethey noted the following: "Dr. F. Layna Serrano...is a native of the province of Guadalajara and knows this whole region. He visited the church at Almadrones before the civil war and saw the apostles when they still hung in the church. He says that the pictures were high on the walls and hard to see. He intended to go back and investigate them further, but the civil war came and he never had another opportunity." See letter from Wethey to G.H.A. Clowes, 5 December 1956, File C10035, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

The Marqués de Lozoya, Director General de Bellas Artes from 1939 to 1951, had the Almadrones paintings taken to the Prado for restoration: “El Sr. Comandante del 'Fuerte de Guadalajara' halló en los desvanes del mismo NUEVE lienzos enrollados los que fueron toscamente restaurados por un sargento aficionado a la pintura, y después se colocaron en un sitio alto y muy poco visible. En una de las visitas que a este centro realizó el Sr. Marqués de Lozoya pudo observar que los aludidos lienzos eran auténticos ‘Grecos’ proponiendo y consiguiendo del señor comandante fueran traidos a los talleres del Prado, para su adecuada restauración como, en efecto, así se hizo. Dichos cuadros representan ‘San Juan,’ ‘Santiago,’ ‘San Felipe,’ ‘San Simón,’ ‘Santo Tomás,’ ‘San Bartolomé,’ ‘San Pablo,’ ‘El Salvaor’ y ‘San Andrés.'” See [Declaration of Francisco J. Sánchez Cantón to the Museum's Patronato], 6 July 1944, Acta del Patronato n◦ 402, Archivo del Museo del Prado, Madrid. (The information in this document was kindly provided to the IMA by Leticia Ruiz in November 2005. As Ruiz observed, the word "NUEVE," in capitals, means that the series was not complete when it arrived at the Prado.) The paintings were received by the Prado on 10 September 1941: "Museo Nacional del Prado. He recibido del señor Teniente Coronel Primer Jefe de los Talleres y Centro electrotécnico de Ingenieros de Guadalajara NUEVE LIENZOS del Apostolado del GRECO, que entrega a este Museo del Prado según órdenes recibidas y que serán restaurados en el mismo. Madrid a 10 de septiembre de 1941." See Expediente de restauración de nueve lienzos del Greco (apostolado) propiedad de la Agrupación de Ingenieros de Guadalajara, 10 September 1941, Archivo del Museo del Prado, Madrid. ↩︎

-

Five paintings, including these three, were restituted to the bishop of Sigüenza in July 1945 and subsequently sold, while the four remaining paintings in the truncated series were acquired by the Spanish Government for the Prado Museum. See Acta de entrega firmada por el Obispo de Sigüenza, 14 July 1945, caja 79, Archivo del Museum del Prado, Madrid. Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor, director of the Prado, stated that five paintings were "shipped out of Spain this year." See Letter from de Sotomayor to G.H.A. Clowes, 21 November 1952, File C10035, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Invoice from Newhouse to G.H.A. Clowes for three paintings, 6 November 1952, File C10035, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

Additional Images