Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

Author

Provenance

Edward Solly (1776–1845), Berlin, by 1819;43

Sold by the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin, in 1923.44

Eilhard Hans Wilhelm Mitscherlich (1901–1979), New York, by 1942;45

Ivan Podgoursky (1901–1962), in 1942;46

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1942;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2004, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10042);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2004.

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 27;

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, 1962, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, no. 2;

Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, China; Hunan Museum, Changsha, China; Chengdu Museum; 2020–21, Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting.

References

Osvald Sirén, Don Lorenzo Monaco (Strassburg: J. H. Ed. Heitz, 1905), 41n1;

Oskar Wulff, “Der Madonnenmeister. Ein sienesisch-florentinischer Trecentist,” Zeitschrift für christliche Kunst 20 (1907): 233;

Oskar Wulff, “Nachlese zur Starnina Frage,” Italienische Studien. Paul Schubring zum 60. Geburtstag gewidmet (Leipzig: K. W. Hiersemann, 1929), 175–176;

Bernard Berenson, Italian Painters of the Renaissance: Florentine School (London: Phaidon, 1963), 1:67;

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 6;

Miklós Boskovits, Pittura Fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento 1370–1400 (Florence: Edam, 1975), 299;

Miklós Boskovits and Erich Schleier, Frühe italienische Malerei. Katalog der Gemälde. Gemäldegalerie (Berlin: Mann, 1988), 38–39;

Miklós Boskovits, “Agnolo Gaddi/Madonna and Child with Saints Andrew, Benedict, Bernard, and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels [entire triptych]/shortly before 1387,” Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/artobject/206122 (n29);

Bruce Cole, Agnolo Gaddi (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press 1977), 27, 30, 82–83 (pl. 37);

Erling Skaug, Punchmarks from Giotto to Fra Angelico. Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting c. 1330 – 1430 (Oslo: Nordisk Konservatorforbund 1994), 1:261; 2, Chart 8.2;

Erling Skaug, “Towards a Reconstruction of the Santa Maria degli Angeli Altarpiece of 1388: Agnolo Gaddi and Lorenzo Monaco?,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 48 (2004): 55;

James France, Medieval Images of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2007), 324, 379 (Compact Disc PA80);

Stefan Weppelmann in“Fantasie und Handwerk.” Cennino Cennini und die Tradition der toskanischen Malerei von Giotto bis Lorenzo Monaco, ed. Wolf-Dietrich Löhr and Stefan Weppelmann, exh. cat. (Berlin: Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2008), 276n3;

Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 14–25 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen, et al., Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 30–33 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen, et al., Floating Lights and Shadows: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 30–33 (reproduced).

Technical Notes and Condition

The four saints have been installed together in a nonoriginal frame.47 The panels originally consisted of individual planks with a vertical grain, cut tangentially (almost certainly from poplar), which had suffered considerable woodworm damage. They were consequently thinned, trimmed, and cradled. Narrow wooden strips were added at the sides, either on one edge alone or on either side. Such intervention removed any trace of barbs left by the removal of the original engaged frames. Remains of punched dots along the left edge of St. Catherine, and to the left and right edges of St. Bernard, as well as above the figure of the saint, indicate that a punched border separated the engaged frame from the picture surface and that the panels terminated in pointed arches.

The technique followed that outlined in Cennino Cennini’s Libro dell’Arte, which is not surprising given that Cennino was Agnolo Gaddi’s assistant for 12 years.48

The planks were first covered with pieces of canvas that were cut to size and did not extend over the engaged frames. Two layers of gesso, gesso grosso and then gesso sottile, followed. No evidence of underdrawing has been detected, either with infrared reflectography or the naked eye. The overall condition of all four panels is good, although there has been some retouching and regilding.

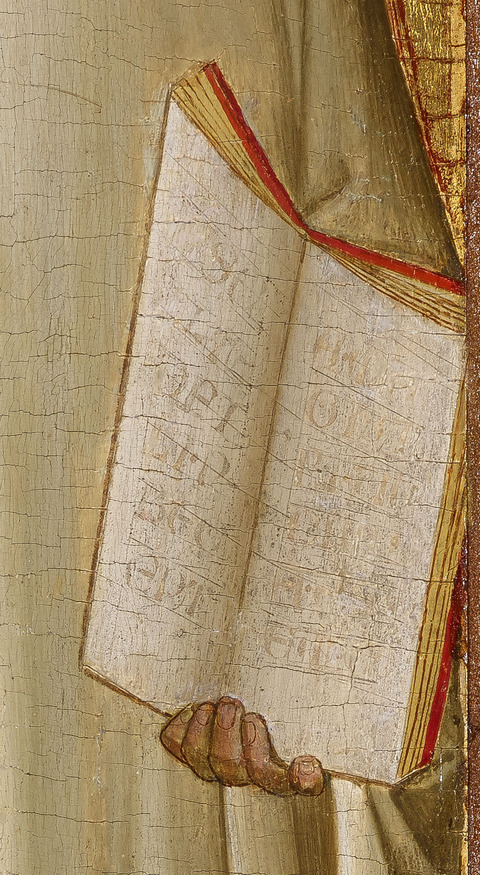

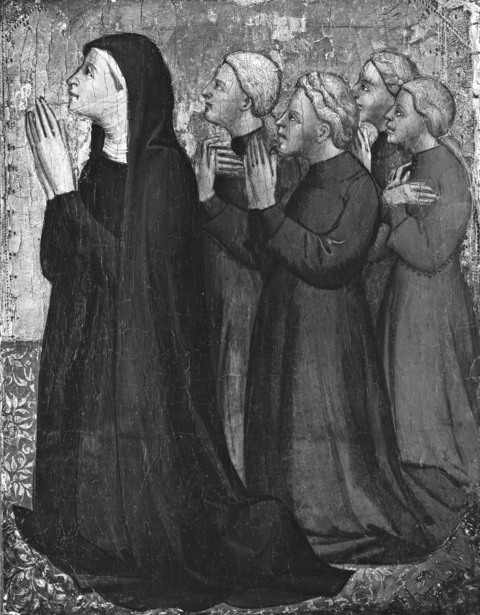

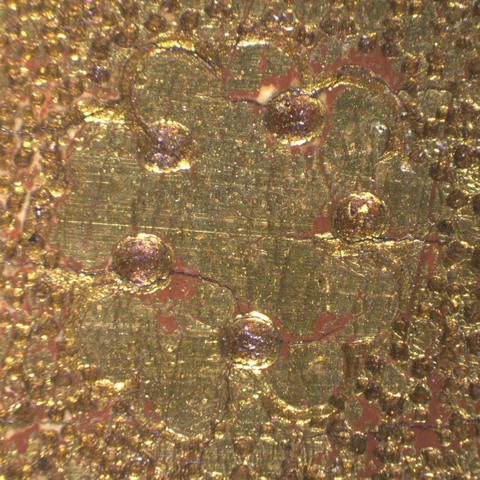

A thick layer of iron-rich red bole was applied to the areas to be water-gilded. Each saint has a slightly different halo pattern, created using different combinations of a few simple punches. All the haloes were punched with a five-lobed floret (see fig. 10).49 In St. Catherine’s halo (fig. 11), a single large dot was added to the center; in the haloes of the other three saints, five dots have been applied between each petal of the floret. A small round punch was used only in the halo of Saint Benedict (fig. 12). The area between the florets was stippled. Clusters of three dots were applied around the haloes in St. Benedict and St. Mary Magdalene. The textile on which the saints stand was done with vermilion painted over the gold and the pattern then scratched out, a technique known as sgraffito (see fig. 6). The draperies were painted before the hands and feet. The skin tones were done with an initial layer of verdaccio, followed by hatched strokes of pink and white. Contours of faces and hands were outlined in brown (see fig. 1). The mordant gilding on the decorative borders of robes was pigmented with white.50 The pigments were standard for this period. Cross-sections taken from the St. Catherine and St. Benedict panels confirm the use of lead-tin yellow II combined with azurite (e.g., for the green of St. Catherine’s dress); vermilion (e.g., in the sgraffito textiles and Mary Magdalene’s robe, and to outline the books held by the saints), yellow ochre, lapis lazuli, red earth (hematite), and red lake.

The marks on the backs of the panels are on the cradles and therefore not original.

Notes

-

Osvald Sirén, Don Lorenzo Monaco (Strassburg: J. H. Ed. Heitz, 1905), 41n1, attributed the Indianapolis panels (then still in Berlin) to a pupil of Agnolo Gaddi, and in “Early Italian Pictures, the University Museum, Göttingen,” The Burlington Magazine 26, no. 141 (1914): 113, he attributed the associated panels with saints (for which see below), which between 1884 and 1976 were on loan from Berlin to the Universitätsmuseum in Göttingen, to a younger artist working in the master’s workshop. Although Oskar Wulff, “Der Madonnenmeister. Ein sienesisch-florentinischer Trecentist,” Zeitschrift für christliche Kunst 20 (1907): 233, attributed the Indianapolis panels to an anonymous Sienese painter working in Florence, he nonetheless acknowledged a proximity to the work of Agnolo Gaddi. Roberto Salvini, “Per la cronologia e per il catalogo di un discepolo di Agnolo Gaddi,” Bollettino d’Arte 29 (1935): 288, stated that Wulff’s “Madonnenmeister” was certainly Florentine and a pupil of Agnolo Gaddi. ↩︎

-

Letter of 10 May 1927 in File C10059, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

For example, Bernard Berenson, Italian Painters of the Renaissance: Florentine School, (London: Phaidon, 1963), 1:67; Miklós Boskovits, Pittura Fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento 1370–1400 (Florence: Edam, 1975), 299; and Bruce Cole, Agnolo Gaddi (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1977), 27, 83. ↩︎

-

Bruce Cole, Agnolo Gaddi (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1977). 27. See also note 13. ↩︎

-

This painting was previously titled Mary Magdalene in the Wilderness, however, given the inclusion of the plant on the left, this is unlikely. According to The Golden Legend, she “retired to an empty wilderness. . . no streams of water there, nor the comfort of grass or trees.” Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan, with introduction by Eamon Duffy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), no. 96, 380. ↩︎

-

It is not clear whether the word C / (ORDIS) was begun at the bottom right-hand page. ↩︎

-

See James France, Medieval Images of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2007), 40–42, and www.cistopedia.org/imagesofbernard, for 1,050 thumbnail images of the saint. The Clowes image is PA198. ↩︎

-

Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan, with introduction by Eamon Duffy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), no. 172, 724. ↩︎

-

Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan, with introduction by Eamon Duffy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), no. 172, 721–723, 726. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits, Pittura Fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento 1370–1400 (Florence: Edam, 1975), 299. Bruce Cole, Agnolo Gaddi (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1977), 27, catalogue 82–83 (pls. 36 and 37), considered the two groups of saints to be associated but from different altarpieces, and the ex-Göttingen saints to be workshop pieces following a design by Agnolo. See also note 1. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits and Erich Schleier, Katalog der Gemälde. Gemäldegalerie Berlin. Frühe italienische Malerei (Berlin: Mann,1988), cat. 19, 38–39, where they are attributed to Agnolo Gaddi. Bruce Cole, Agnolo Gaddi (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1977), 27, had also suggested that as an alternative to pilasters the Clowes saints might have been wings of an altarpiece. See further Stefan Weppelmann in “Fantasie und Handwerk.” Cennino Cennini und die Tradition der toskanischen Malerei von Giotto bis Lorenzo Monaco, ed. Wolf-Dietrich Löhr and Stefan Weppelmann, exh. cat. (Berlin: Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2008), 276n3. ↩︎

-

See Miklós Boskovits, “Agnolo Gaddi/Madonna and Child with Saints Andrew, Benedict, Bernard, and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels [entire triptych]/shortly before 1387,” Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/artobject/206122 (note 29), citing Kanter’s view. ↩︎

-

Domenico Maria Manni, Osservazioni istoriche sopra i sigilli antichi de’secoli bassi (Florence: Nella Stamperia dell’Autore, 1743), 14:12–13; Giuseppe Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese Fiorentine (Florence: Nella Stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1759), 8:149. ↩︎

-

For the monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, see Divo Savelli and Rita Nencioni, Il Chiostro degli Angeli. Storia dell’Antico monastero camaldolese di Santa Maria degli Angeli a Firenze (Florence: Edizioni Polistampa, 2008); and Cristina De Benedictis, Carla Milloschi, and Guido Tigler eds., Santa Maria degli Angeli a Firenze: da monastero camaldolese a Biblioteca Umanistica (Florence: Nardini editore, forthcoming). For the chapels and altarpieces in the monastery, see George Bent, “Santa Maria degli Angeli and the Arts: Patronage, Production and Practice in a Trecento Florentine Monastery,” Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1993; George Bent, Monastic Art in Lorenzo Monaco’s Florence: Painting and Patronage in Santa Maria degli Angeli, 1300–1415 (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2006); Dillian Gordon, “The Fourteenth-Century Altars and Chapels in the Camaldolese Monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence: The Saving of Souls more laudabili,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 3 (2013): 289–314; Dillian Gordon, “The Paintings from the Early to the Late Gothic Period,” in Santa Maria degli Angeli a Firenze: Da monastero camaldolese a Biblioteca Umanistica, ed. Cristina De Benedictis, Carla Milloschi, and Guido Tigler (Florence: Nardini editore, forthcoming). ↩︎

-

For information on Bernardo and his family, see Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 16, 18–19 (whole article 14–25). ↩︎

-

Domenico Maria Manni, Osservazioni istoriche sopra i sigilli antichi de’secoli bassi (Florence: Nella Stamperia dell’Autore, 1743), 14:13; Giuseppe Richa: Notizie istoriche delle chiese Fiorentine (Florence: Nella Stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1759), 8:149. ↩︎

-

Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Diplomatico, Firenze, Santa Maria degli Angioli, 9 November 1388 (00077476). Both Domenico Maria Manni, Osservazioni istoriche sopra i sigilli antichi de’secoli bassi (Florence: Nella Stamperia dell’Autore, 1743), 14:13, and Giuseppe Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese Fiorentine (Florence: Nella Stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1759), 8:150, give the date of the codicil as 16 November 1388. ↩︎

-

See Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 16. ↩︎

-

See Stefano Rosselli, Sepoltuario, Archivio di Stato Firenze, Manoscritti, 625, ff. 1324–1325, no. 16, with a sketch of the arms, cited by Dillian Gordon, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2003), 197n3. ↩︎

-

Giuseppe Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese Fiorentine (Florence: Nella Stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1759), 8:166. ↩︎

-

Most recently, Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 14–25. ↩︎

-

Hans D. Gronau, “The Earliest Works of Lorenzo Monaco—II,” The Burlington Magazine 92 (1950): 217–222. See also Marvin Eisenberg, Lorenzo Monaco (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 200–201 (under “ascribed to Lorenzo Monaco,” although Eisenberg saw them generally as by the workshop of Agnolo). ↩︎

-

For the Baptism of Christ, see Dillian Gordon, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2003), 1:192–197. The Baptism is first recorded in the Warner Ottley Sale, 30 June 1847, and was presumably in the collection of William Young Ottley (1771–1836), who was in Italy from 1791 to 1799. ↩︎

-

Federico Zeri, “Investigations into the Early Period of Lorenzo Monaco—I,” The Burlington Magazine 106, no. 741 (1964): 554–558; reprinted in Giorno per Giorno nella Pittura. Scritti sull’Arte Toscana dal Trecento al primo Cinquecento (Turin: U. Allemandi, 1991), 103–106. ↩︎

-

Sold Sotheby’s New York, 29 January 2009, lot 8. With Robert Langton Douglas by 1920. ↩︎

-

Formerly in a private collection in Milan. ↩︎

-

Domenico Maria Manni, Osservazioni istoriche sopra i sigilli antichi de’secoli bassi (Florence: Nella Stamperia dell’Autore, 1743), 14:16. ↩︎

-

I am grateful to Larry Kanter for sharing his identification with me and for encouraging me to publish it. See Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 14–25. ↩︎

-

Bruce Cole, Agnolo Gaddi (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1977), pl.1, 75. ↩︎

-

Erling Skaug, “Towards a Reconstruction of the Santa Maria degli Angeli Altarpiece of 1388: Agnolo Gaddi and Lorenzo Monaco?,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 48 (2004): 245–257. ↩︎

-

Giuseppe Richa, Notizie istoriche delle chiese Fiorentine (Florence: Nella Stamperia di Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1759), 8:166. ↩︎

-

Erling Skaug, “Towards a Reconstruction of the Santa Maria degli Angeli Altarpiece of 1388: Agnolo Gaddi and Lorenzo Monaco?,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 48 (2004): 254–255, with illustrations and chart. I am very grateful to Erling Skaug for his help in this matter. ↩︎

-

Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 23. ↩︎

-

Caterina is first named with her three sisters in Bernardo’s will of 21 June 1385 (Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Notarile Antecosimiano 6177, ff. 156 verso). It is interesting to note that Bernardo had a slave called Caterina, to whom he bequeathed her liberty in the same will. For Bernardo’s several wills, see Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 17n23 and 18. Henry Tann kindly tracked down the wills on my behalf. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits, “Agnolo Gaddi/Madonna and Child with Saints Andrew, Benedict, Bernard, and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels [entire triptych]/shortly before 1387,” Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/artobject/206122 (note 29). The Clowes saints have been cradled (see Technical Examination Report), which renders useless any attempt to fit the panels one above the other by matching patterns in the wood grain via X-rays. ↩︎

-

See Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 22. ↩︎

-

Bruce Cole, Agnolo Gaddi (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1977), 27. ↩︎

-

Noted also by Bruce Cole, Agnolo Gaddi (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1977), 27, who identifies the figure as St. Stephen. ↩︎

-

See Erling Skaug in Lorenzo Monaco: A Bridge from Giotto’s Heritage to the Renaissance, ed. Angelo Tartuferi and Daniela Parenti, exh. cat (Florence: Giunti Editore S. P. A., 2006), cat. 5, 106–111. ↩︎

-

See Dillian Gordon, “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence,” The Burlington Magazine 162 (January 2020): 24. ↩︎

-

Solly, an English timber and grain merchant, resided in Berlin from about 1813 to 1819. He had assembled a collection of more than 3,000 paintings, which were purchased by the Prussian State by contract in 1819, forming one cornerstone of what would become the Gemäldegalerie Berlin; see Christoph Marin Vogtherr, “Das Königliche Museum zu Berlin: Planungen und Konzeption des ersten Berliner Kunstmuseums,” Jahrbuch der Berliner Sammlungen N.F. 39, Berlin 1997, 95–114. The Gaddi panels, then attributed to Orcagna (Andrea di Cione, died 1368), are first included in an 1821 inventory, as no. Tö 14, prepared by Ernest Heinrich Toelken. The first detailed inventory was conducted in 1823, and three sequential entries (nos. M74, 75, 76) cover the main tier panels in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the ex-Göttingen panels (now back in the Gemäldegalerie) and the Clowes panels (M76).

By 1829/30, when the Clowes panels were catalogued as no. III 41, the attribution had changed to Florence, about 1400. The author wishes to thank Robert Skwirblies, Technische Universität, Berlin, for his help in providing information on the Nobili altarpiece panels that were in the Solly Collection. See also Robert Skwirblies, “‘Ein Nationalgut, auf das jeder Einwohner stolz sein dürfte’: Die Sammlung Solly als Grundlage der Berliner Gemäldegalerie, Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 51, 2009, 69–99, especially 75, 95, for digests of the relevant inventories. ↩︎

-

Letter from Erich Schleier, Berlin, to the IMA, 19 March 1976, File C10042, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Bill of sale, Mitscherlich to Podgoursky, 24 February 1942, File C10042, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Bill of sale, Podgoursky to G.H.A. Clowes, 24 February 1942, File C10042, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Podgoursky met Clowes in the late 1930s, selling him several paintings over the following decades. ↩︎

-

A photograph of the painting in a modern frame previous to the present one is to be found in Oskar Wulff, “Nachlese zur Starnina Frage,” Italienische Studien. Paul Schubring zum 60. Geburtstag gewidmet (Leipzig 1929), 175. ↩︎

-

For a description of the technique of early Italian panel paintings, see David Bomford, Jill Dunkerton, Dillian Gordon, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Italian Painting before 1400, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery, 1989), esp. 9–51. ↩︎

-

Skaug no. 441. See Erling Skaug, “Towards a Reconstruction of the Santa Maria degli Angeli Altarpiece of 1388: Agnolo Gaddi and Lorenzo Monaco?” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 48 (2004): 255. ↩︎

-

For another example of Lorenzo Monaco using lead white to pigment the mordant, see his altarpiece for San Benedetto fuori della Porta Pinti of 1407–1409; Dillian Gordon, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2003), 1:168. ↩︎