Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

Author

Provenance

Angela Rossati Bono, Venice, probably by decent within the family of the sitter;50

(Arturo Grassi, Florence and New York);51

G.H. A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1935;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, 1958–2016, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10074);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2016.

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 55, as Titian;

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 47, as Titian;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1965, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, no. 20, as Titian;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection, as Workshop of Titian.

References

Catalogue of the Paintings and Sculpture given by Edgar B. Whitcomb and Anna Scripps Whitcomb to the Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1954), 107;

William Suida, “Miscellanea Tizianesca—Part II,” Arte Veneta 10 (1956): 76 [71–81], fig. 74. (reproduced);

Bernard Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Venetian School (New York: Phaidon Press, 1957), 1:186;

Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), no. 55 (reproduced);

Francesco Valcanover, Tutta la pittura di Tiziano (Milan: Rizzoli, 1960), 2:66, no. 155B (reproduced);

A Lenten Exhibition, exh. cat. (Notre Dame, IN: The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, 1962), no. 47;

Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, exh. cat. (Bloomington: Indiana University Art Museum, 1965), no. 20;

Francesco Valcanover, All the Paintings of Titian, trans. Sylvia J. Tomalin, part 4 (New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1965), 98, no. 155b (reproduced);

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

Rodolfo Pallucchini, Tiziano, 2 vols. (Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1969), 1:223 and 348; 2: fig. 672 (reproduced);

Francesco Valcanover, L’opera completa di Tiziano (Milan: Rizzoli, 1969), 107, no. 157 (reproduced);

Harold E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian (London: Phaidon Press, 1971), 2:164, no. X-39, pl. 253 (reproduced);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 26 (reproduced);

Fern Rusk Shapley, Catalogue of the Italian Paintings (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1979), 1:508;

Terisio Pignatti, Titian, ed. David Piper, trans. Judith Landry (New York: Rizzoli, 1981), 2:78, no. 574 (reproduced); John Shearman, The Early Italian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 270;

Filippo Pedrocco, Titian (New York: Rizzoli, 2001), 152;

Deborah Howard, “Titian’s Portraits of Grand Chancellor Andrea de' Franceschi,” Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (2016): 146 [139–151], fig. 8 (reproduced).

Technical Notes and Condition

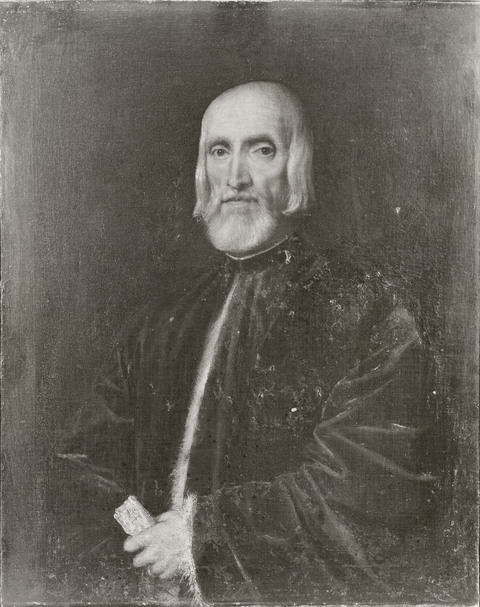

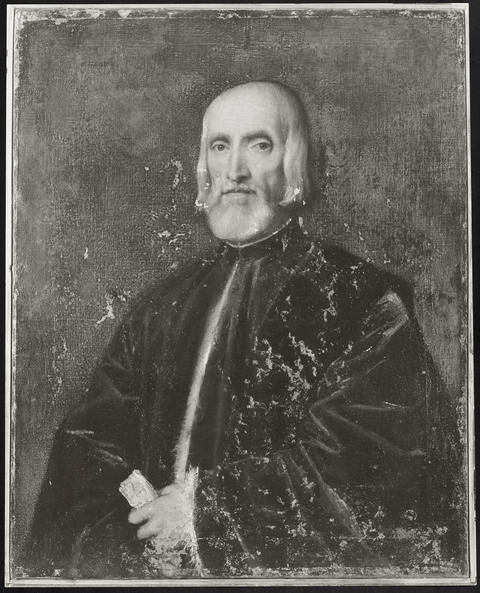

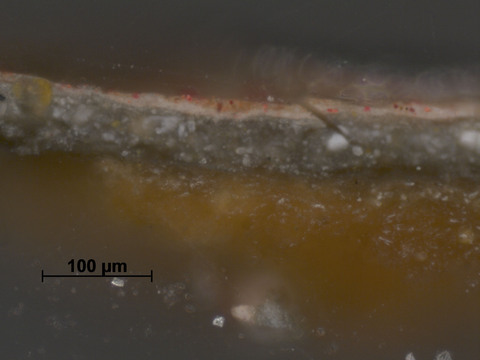

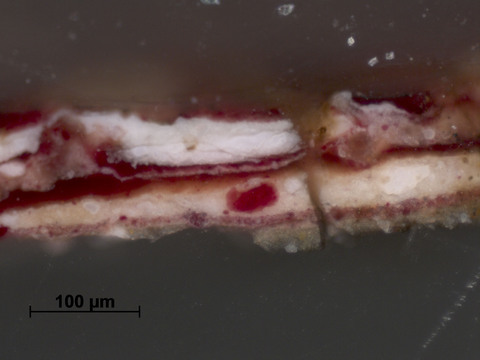

Cusping along all four edges indicates that the canvas is close to its original size. From damage visible in the X-ray there is evidence to suggest that, at one point, it was resized to fit a smaller stretcher. This is evident from lines along all four sides of the canvas (consistent with loss of ground and paint) that indicate a folding edge. This was later reincorporated into the current composition, so that the painting is now closer to its original size. The original plain-weave canvas has been glue lined with a more thickly woven lining canvas. Infrared reflectography reveals evidence of underdrawing used to sketch the general form of the sitter in areas around the head, robe, and hand. The paint is medium thickness and loosely applied with broad brushstrokes, with the exception of the areas of the face and hand that show a finer handling. There is filling and retouching in areas of previous damage and loss primarily in the sitter’s hand, robe, and background. The writing on the letter is abraded beyond legibility. The painting is in stable condition. Past conservation treatments include removal of overpainting and discolored varnish, stabilization of flaking, inpainting, and varnishing.

Notes

-

I am thankful to Professor Deborah Howard and Dr. Carlo Corsato for their perceptive comments on an earlier version of this essay. I am also grateful to Professor Peter Humfrey for his generous advice. During the final stages of this essay’s preparation, I benefited greatly from the expertise and practical assistance of Professor Paul Joannides.

Sergio Zamperetti, “Andrea de' Franceschi,” in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 36 (Rome, 1988): 24–26. Thomas Weigel, “Begräbniszeremoniell und Grabmäler venezianischer Grosskanzler des 16 Jahrhunderts,” in Praemium Virtutis: Grabmonumente und Begräbniszeremoniell im Zeichen des Humanismus, ed. Joachim Poeschke, Britta Kusch, and Thomas Weigel (Münster: Rhema, 2002), 147–173, especially 148 and 165–67. An eighteenth-century print identifies the sitter as De' Franceschi. On this identification, see Deborah Howard, “Titian’s Portraits of Grand Chancellor Andrea de' Franceschi,” Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (2016): 139–151, especially 143. ↩︎

-

Harold E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian: Complete Edition (London: Phaidon Press, 1971), 2:164, cat. no. X-39, pl. 253. Harold Wethey’s three-volume (1969–1975) catalogue raisonné remains the most thorough treatment of the Titian’s oeuvre. Other catalogues include Rodolfo Pallucchini, Tiziano, 2 vols. (Florence: G.C. Sansoni, 1969); Francesco Valcanover, L’opera completa di Tiziano (Milan: Rizzoli, 1969); Terisio Pignatti, Titian, ed. David Piper, trans. Judith Landry (New York: Rizzoli, 1981); Filippo Pedrocco, Titian (New York: Rizzoli, 2001); and Peter Humfrey, Titian: The Complete Paintings (Ghent: Ludion, 2007). ↩︎

-

As a sign of rank, the grand chancellor wore a robe of deep red or purple (paonazo). Within the hierarchy of the Chancery, the wearing of crimson (the most lavish red) was followed by scarlet, worn by the secretaries of the Council of Ten. Stella Mary Newton, The Dress of the Venetians, 1495–1525 (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1988), 23–24. Venetian politics were as distinctive as its lagunar environment. On Venetian history, see David Rosand, Myths of Venice: The Figuration of a State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007). In the sixteenth century, Venice’s social hierarchy broadly consisted of three main divisions: 4.5% nobles (patriciate), 5.3% citizenry (e.g., merchants, lawyers, doctors, and civil servants), and 90% general population (e.g., artisans, laborers, servants, and slaves). This abbreviated outline serves to underscore De' Franceschi’s elite standing within Venice’s incredibly complex social matrix. On this hierarchy, see Stanley Chojnacki, “Social Identity in Renaissance Venice: The Second Serrata,” Renaissance Studies 8, no. 4 (1994): 341–358, and Gerhard Rösch, “The Serrata of the Great Council and Venetian Society, 1286–1323,” in Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, 1297–1797, ed. John Martin and Dennis Romano (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 67–88. Specifically, De' Franceschi was a cittadino originario, or “original” citizen. David Chambers, Jennifer Fletcher, and Brian Pullan, Venice: A Documentary History 1450–1630 (Toronto, Buffalo, and London: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 276–278. ↩︎

-

On the Chancery, see David Chambers, Jennifer Fletcher, and Brian Pullan, Venice: A Documentary History 1450–1630 (Toronto, Buffalo, and London: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 59–61. On the College of Secretaries, see Margaret L. King, Venetian Humanism in an Age of Patrician Dominance (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986), 76–79. ↩︎

-

Felix Gilbert, “The Last Will of a Venetian Grand Chancellor,” in Philosophy and Humanism: Renaissance Essays in Honor of Paul Oskar Kristeller, ed. E.P. Mahoney (Leiden: Brill, 1976), 502–17, on 516. Also see Deborah Howard, “Contextualising Titian's ‘Sacred and Profane Love’: The Cultural World of the Venetian Chancery in the Early Sixteenth Century,” Artibus et Historiae 34, no. 67 (2013): 186. ↩︎

-

Andrea de' Franceschi, Itinerario di Germania delli Magnifici Ambasciatori Veneti m. Giorgio Contarini, Conte di Zapho, e m. Paolo Pisani alli Serenissimi Federico III Imperatore et Maximiliano, suo fiolo, Re dei Romani, ed. E. Simonsfeld, in Miscellanea di storia veneta 9 (1903): 277–345. ↩︎

-

On De' Franceschi’s career, see Sergio Zamperetti, “Andrea de' Franceschi,” in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 36 (Rome, 1988), 24–26. ↩︎

-

Stella Mary Newton, The Dress of the Venetians, 1495–1525 (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1988), 23–24. On sumptuary laws and fashion, see Jane Bridgeman, “‘Pagare le Pompe’: Why Quattrocento Sumptuary Laws Did Not Work,” in Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society, ed. Letizia Panizza (Oxford: Legenda, 2000), 207–226. ↩︎

-

Types of fur used to line Venetian garments include marten, sheared lamb, wolf, squirrel, and miniver. Stella Mary Newton, The Dress of the Venetians, 1495–1525 (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1988), 11. ↩︎

-

Paul Hills, Venetian Colour: Marble, Mosaic, Painting, and Glass, 1250–1550 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999). ↩︎

-

For a general discussion of the debate, or paragone, between design and color, see Claire Pace, “Disegno e Colore,” in The Dictionary of Art, vol. 9 (New York: Grove, 1996), 6–7. ↩︎

-

“E certo il colorito è di tanta importanza e forza, che quando il pittore va imitando bene le tinte e la morbidezza delle carni, e la proprietà di qualunque cosa, fa parer le sue pitture vive….” Lodovico Dolce, Dialogo della pittura (Venice: Gabriele Giolito, 1557), 216, as quoted in Claire Pace, “Disegno e Colore,” in The Dictionary of Art, vol. 9 (New York: Grove, 1996), 7. ↩︎

-

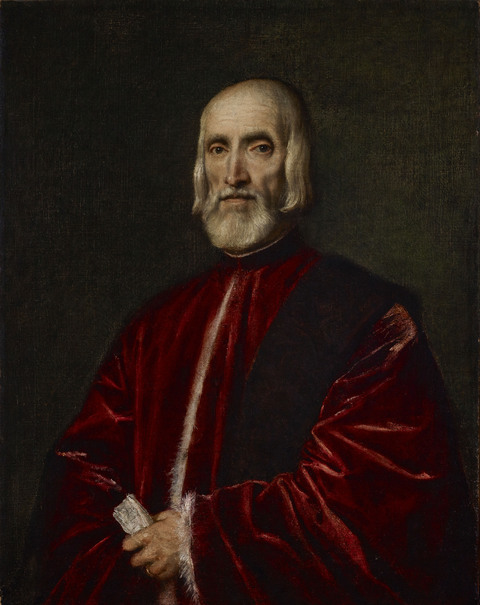

Harold E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian: Complete Edition (London: Phaidon Press, 1971), 2:100–101, cat. no. 34, pl. 63. John Shearman, The Early Italian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 270. Portrait information given here is taken from the website of the holding institution. Detroit Institute of Arts, “Titian, Andrea dei Franceschi, ca. 1532 (53.362),” accessed 17 May 2022, https://www.dia.org/art/collection/object/andrea-dei-franceschi-63579. Also see Peter Humfrey, Titian: The Complete Paintings (Ghent: Ludion, 2007), 149, cat. no. 99. ↩︎

-

Many thanks to David Essex, curatorial assistant, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, and Anne Halpern, Department of Curatorial Records, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, for facilitating access to this painting and its documents on 31 August 2017. Harold E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian: Complete Edition (London: Phaidon Press, 1971), 2:100–101, cat. no. 35, pl. 61. Portrait information given here is taken from the website of the holding institution. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, “Andrea dei Franceschi, late 16th or early 17th century (1937.1.35),” accessed 17 May 2022, https://purl.org/nga/collection/artobject/42. In this portrait, the robe is scarlet red, a hue associated with the secretaries of the Council of Ten, but they were also known to have worn black. Email communication between Rebecca Norris and Jola Pellumbi, 22 July 2017. Also see Jola Pellumbi, “Revealing and Concealing: Official Male Dress in Early Modern Venice, 1520–1610,” PhD thesis, King’s College University, London, 2017. ↩︎

-

Most recently on this painting see Peter Humfrey, “Anonymous Artist, Titian/Andrea de' Franceschi/late 16th or early 17th century,” Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century, NGA Online Editions, accessed 14 January 2021, https://purl.org/nga/collection/artobject/42. ↩︎

-

My thanks to Lucy Whitaker, senior curator of paintings of the Royal Collection Trust, for granting access to the painting on 29 June 2017. Portrait information given here is taken from the website of the holding institution. Royal Collection Trust, “After Titian, Titian and His Friends, 1550–1560 (RCIN 402841),” accessed 17 May 2022, https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/themes/exhibitions/portrait-of-the-artist/the-queens-gallery-buckingham-palace/titian-and-his-friends. On this portrait, also see Deborah Howard, “Titian’s Portraits of Grand Chancellor Andrea de' Franceschi,” Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (2016): 139–151. ↩︎

-

On the Berlin and San Francisco portraits, the information given here is taken from the websites of their respective holding institutions. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, “Tiziano, Self-Portrait (163),” accessed 17 May 2022, http://www.smb-digital.de/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=872023&viewType=detailView. Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, “Titian, Portrait of a Friend of Titian (Marco Mantova Benavides), about 1550 (61.44.17),” accessed 17 May 2022, https://art.famsf.org/tiziano-vecellio-titian/portrait-friend-titian-marco-mantova-benavides-614417. On the identity of the sitter and interpretation of the inscribed letter in the San Francisco portrait, see Charles Davis, “Titian, ‘A singular friend,'” in Kunst und Humanismus: Festschrift für Gosbert Schüßler zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. Wolfgang Augustyn and Eckhard Leuschner (Passau: Dietmar Klinger Verlag, 2007), 261–301. ↩︎

-

Deborah Howard, “Titian’s Portraits of Grand Chancellor Andrea de’ Franceschi,"Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (2016): 139–151. On patronage and members of the Chancery, see Deborah Howard, “Contextualising Titian's ‘Sacred and Profane Love’: The Cultural World of the Venetian Chancery in the Early Sixteenth Century,” Artibus Et Historiae 34, no. 67 (2013): 187. For comparative studies on citizenry patronage, see Blake de Maria, Becoming Venetian: Immigrants and the Arts in Early Modern Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), and Monika Schmitter, “‘Virtuous Riches’: The Bricolage of Cittadini Identities in Early Sixteenth-Century Venice,” Renaissance Quarterly 57, no. 3 (Autumn, 2004): 908–969. ↩︎

-

“…il retratto mio secundo facto de mano de Ticiano…. Item il mio primo ritracto depento da mano de Tician.” Testament dated 1 March 1535 transcribed in Michel Hochmann, Peintres et Commanditaires à Venise 1540–1628 (Rome: École Française de Rome, 1992), 357–358. Ridolfi states, “il quello del Gran Cancellier Franceschi.” He claimed to have seen the portrait in the Palazzo Widmann (also spelled Widman, Vidmani, and Vidiman). Carlo Ridolfi, Le maraviglie dell’arte: Ovvero Le vite degli illustri pittori veneti e dello stato, ed. Detlev Freiherrn von Hadeln (Berlin: G. Grote, 1914), 1:201. For a transcription of the inventory of paintings in the Palazzo Widmann mentioning the portrait of the grand chancellor by Titian, see Fabrizio Magani, Il Collezionismo e la committenza artistica della famiglia Widmann, patrizia veneziani, dal seicento all’ottocento (Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 1989) 33–42, especially 34 and 42. In tracking the provenance, it is not clear if the Widmanns were descendants of De' Franceschi. Franz Schroeder, Repertorio genealogico delle famiglie confermate nobili e dei titolati nobili esistenti nelle provincie venete (Venice: Alvisopoli, 1830), 372–373. ↩︎

-

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968). ↩︎

-

Harold E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian (London: Phaidon, 1971), 2:164, cat. no. X-39. Wethey was in correspondence with the Clowes and had visited the Clowes Collection while researching his earlier book, El Greco and His School (1962), and it follows that he would also have had access to the Portrait of Andrea de’ Franceschi. Letter from George H.A. Clowes to Harold Wethey, 18 November 1957, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

I am grateful to Eve Straussman-Pflanzer, Elizabeth and Allan Shelden Curator of European Paintings, and Ellen Hanspach-Bernal, conservator of paintings, at the Detroit Institute of Arts, and also to my colleagues Fiona Beckett, former Clowes conservator of paintings, and Erica Schuler, former Clowes fellow in paintings conservation, for sharing their observations while examining the Portrait of Andrea dei Franceschi (53.362) during our consultation at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Visual examination at the Detroit Institute of Arts, 21 September 2016. ↩︎

-

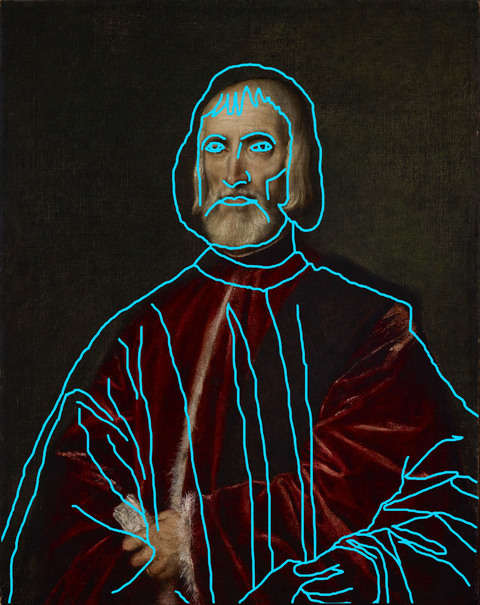

Similar analysis using comparative tracings are illustrated in Miguel Falomir, “Titian’s Replicas and Variants,” in Titian, ed. David Jaffé (London: National Gallery, 2003), 60–73. ↩︎

-

Replication arose in response to the growing demands of artistic patronage and was an established practice in artists' workshops, such as that of the Venetian painter Giovanni Bellini (1431/1436–1516). See Andrea Golden, “Creating and Re-creating: The Practice of Replication in the Workshop of Giovanni Bellini,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 91–127. Regarding Titian, see Miguel Falomir, “Tiziano: réplicas,” in Tiziano, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo del Prado, 2003), 77–91, 326–332. Giorgio Tagliaferro, Bernard Aikema, Matteo Mancini, and Andrew John Martin, Le botteghe di Tiziano (Florence: Alinari 24 Ore, 2010). On replicas, see Paul Joannides, “An Attempt to Situate Titian’s Paintings of the Penitent Magdalene in Some Kind of Order,” Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 73 (2016): 157–194; Paul Joannides, “Titian’s Repetitions,” in Titian: Materiality, Likeness, Istoria, ed. Joanna Woods-Marsden (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), 37–49, on 37–38. Bruce Cole, “Titian and the Idea of Originality in the Renaissance,” in Andrew Ladis, Carolyn Wood, and William U. Eiland, The Craft of Art: Originality and Industry in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque Workshop (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995), 86–112. Hans Tietze, “An Early Version of Titian’s Danae: An Analysis of Titian’s Replicas,” Arte Venete 8 (1954): 199–208. ↩︎

-

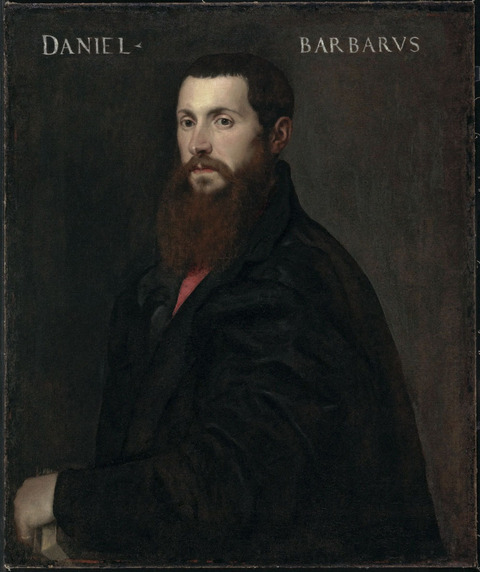

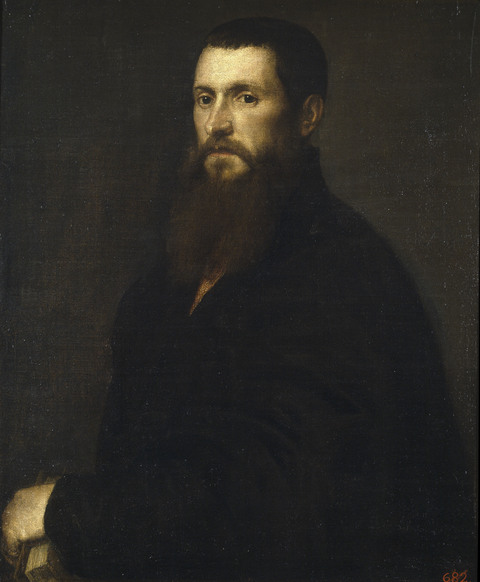

Portrait information given here is taken from the websites of the holding institutions. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, “Titian, Daniele Barbaro, 1545 (3567),” accessed 17 May 2022, https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artwork/daniele-barbaro. Peter Zimonjic, “Re-claiming Titian,” National Gallery of Canada, 6 December 2012, accessed 17 May 2022, https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/in-the-spotlight/re-claiming-titian. Museo del Prado, “Titian, Daniele Barbaro, Patriarch of Aquileia, about 1545 (P00414),” accessed 17 May 2022, https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/daniele-barbaro-patriarch-of-aquileia/642c4a9c-6894-47a4-a328-abe97b4626f0. Also see Peter Humfrey, Titian: The Complete Paintings (Ghent: Ludion, 2007), 196–197, cat. nos. 141–42; Miguel Falomir, “Tiziano: réplicas,” in Tiziano, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo del Prado, 2003), 198, cat. no. 25, 373–374. ↩︎

-

Charles Hope, “Titian’s Life and Times,” in Titian, ed. David Jaffé (London: National Gallery, 2003), 9–28, especially 18–20. ↩︎

-

Carlo Ridolfi, Le maraviglie dell’arte: Ovvero Le vite degli illustri pittori veneti e dello stato, ed. Detlev Freiherrn von Hadeln (Berlin: G. Grote, 1914), 2:178. ↩︎

-

There is no specific mention linking De' Franceschi and Titian in contemporary writings by those such as Marino Sanudo (1466–1536), Pietro Aretino, Lodovico Dolce, or Francesco Sansovino (1521–1586). Aretino was an author, playwright, poet, and satirist who had attained considerable wealth and influence, in part through literary flattery and infamous blackmail. He directly contributed to Titian’s celebrity through his widely published letters. Pietro Aretino, Lettere sull’arte di Pietro Aretino, ed. Ettore Camesasca, 3 vols. (Milan, 1557). ↩︎

-

Carlo Ridolfi, Le maraviglie dell’arte: Ovvero Le vite degli illustri pittori veneti e dello stato, ed. Detlev Freiherrn von Hadeln (Berlin: G. Grote, 1914), 1:154. For the argument against De' Franceschi’s portrayal in the Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple, see David Rosand, “Titian’s Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple and the Scuola della Carità,” The Art Bulletin 58, no. 1 (March, 1976): 55–84, on 76. Also see Bernard Berenson, “While on Tintoretto,” in Festschrift von Max J. Friedländer zum 60. Geburtstage (Leipzig: E. A. Seemann, 1927), 224–243, especially 232; Suida notes, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. However, De' Franceschi appears featured in Palma il Giovane’s Pope Alexander III and Doge Ziani Sending Otto to Negotiate Peace with His Father Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, dated to the 1580s (Venice, Ducal Palace). This posthumous inclusion is curious, as is the teal color of his robe. (A variant of paonazzo?) ↩︎

-

The sanseria was a coveted privilege that provided for an annuity, and it was awarded to the foremost artists of Venice. On this see Charles Hope, “Titian's Role as Official Painter to the Venetian Republic,” in Tiziano e Venezia: Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Venezia 1976 (Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 1980), 301–305. On the sanseria as the possible basis for their friendship, see Deborah Howard’s discussion in “Titian’s Portraits of Grand Chancellor Andrea de' Franceschi,"Artibus et Historiae 37, no. 74 (2016): 147n33. ↩︎

-

On the mention of favors, see Jennifer Fletcher, “Tiziano retratista,” in Tiziano, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo del Prado, 2003), 63–75 and 320–326, especially 321. ↩︎

-

On the cittadino originario, see note 3. Grand chancellors received a relatively substantial salary. De' Franceschi’s wealth is enumerated in his testament, which lists household possessions that reflect a sophisticated range of objects, including silverware with the family coat of arms; books, such as a copy of Homer printed by the famous Aldine Press; various antiquities, including ancient Greek and Roman coins; a marble bust “that was always kept on my table”; and even a harpsichord. These objects personalize the image of a rich and cultured life. Michel Hochmann, Peintres et Commanditaires à Venise 1540–1628 (Rome: École Française de Rome, 1992), 357–358. De' Franceschi’s musical appreciation is documented in his Itinerario. See note 6. ↩︎

-

The certificates of expertise by George Gronau, Giuseppe Fiocco, and Evelyn Sandberg-Vavalà, are dated respectively 2 August 1928, 20 August 1928, and 1 January 1935, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Such documents are illustrative of early twentieth-century appraisal practices, as well as of perceptions of authority and connoisseurship. The three written for this portrait provide comparative approaches to the practice. ↩︎

-

Undated notes written by William Suida, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Writing in a later article, Suida maintained his support of the Titian attribution. William Suida, “Miscellanea Tizianesca—Part II,” Arte Veneta 10 (1956): 76–78. ↩︎

-

Portrait information given here is taken from the websites of the holding institutions. Museo del Prado, “Titian, Philip II, 1551 (P00411),” accessed 17 May 2022, https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/philip-ii/d12e683b-7a51-41db-b7a8-725244206e21. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, “Portrait of Marcantonio Trevisan, Doge of Venice, ca. 1553–1554 (4223),” accessed 17 May 2022, https://www.szepmuveszeti.hu/mutargyak/marcantonio-trevisan-dozse-kepmasa/. ↩︎

-

Bernard Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance (Phaidon: New York, 1957), 1: x–xi, 186. That Berenson did not have intimate knowledge of the portrait is indicated by a letter in which Dr. Clowes offered to share with Berenson, via his assistant Dr. Luisa Vertova, information on his collection, including the Portrait of Andrea de’ Franceschi. Letter from G.H.A. Clowes to Luisa Vertova, 24 March 1954, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Regarding the three treatments by Suhr dated to 1935, 1955, and 1960, see the letters from G.H.A. Clowes to Arturo Grassi, 13 June 1935; Arturo Grassi to G.H.A. Clowes, 27 June 1935; G.H.A. Clowes to William Suhr, 20 October 1955; and William Suhr to Edith Whitehill Clowes, 11 January 1960, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. William Suhr Papers, Series 1, Box 79, Special Collections, Getty Research Institute, The J. Paul Getty Trust, http://archives2.getty.edu:8082/xtf/view?docId=ead/870697/870697.xml. Incidentally, Suhr also treated the Detroit portrait. Conservation notes, Detroit Institute of Arts, 21 September 2016. According to Dr. Clowes, at the time of the portrait’s first treatment, Suhr was still working at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Letter from G.H.A. Clowes to E.P. Richardson, 30 March 1950. Evidence exists for two other unconfirmed treatments. One was proposed in a letter from Ludwig Furst to G.H.A. Clowes, 4 January 1949; and another that was initially proposed and then cancelled is mentioned over the course of several letters written between Allen Clowes and the restorer Daniel Goldreyer in the period from 1 February 1962 to 20 July 1962, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. According to two letters dated to 1964, Goldreyer was to resume restoration, but there is no documentation to confirm that this work was, in fact, executed. Letter from Daniel Goldreyer to Edith Whitehill Clowes, 21 April 1964, and letter from Daniel Goldreyer to Allen Clowes, 6 May 1964, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from G.H.A. Clowes to Arturo Grassi, 13 June 1935, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Arturo Grassi to George H.A. Clowes, 27 June 1935, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

William Suhr Papers, Series 1, Box 79, Special Collections, Getty Research Institute, The J. Paul Getty Trust. ↩︎

-

Letter from William Suhr to Edith Whitehill Clowes, 11 January 1960, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. That this treatment was executed is indicated by a handwritten note on the letter by Mrs. Clowes: “Jan. 14, 1960 Please proceed with the above—E. W. Clowes.” ↩︎

-

Harold E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian (London: Phaidon, 1971), 2:164. Presumably, Wethey was familiar with the portrait through his previous contact with Dr. Clowes. See note 21. ↩︎

-

I am indebted to my colleague Fiona Beckett, the Clowes Conservator of Paintings, for her expert sampling and material analysis. Many thanks also to Gregory Dale Smith, Otto N. Frenzel III Senior Conservation Scientist of Newfields' Conservation Science Lab, for his assistance with material analysis. Sampling and technical analysis conducted in March 2017, in part, assisted by the author. Results from this analysis were co-presented by Fiona Beckett and Rebecca Norris, “Technical Analysis of the Portrait of Andrea de' Franceschi by Titian’s Workshop,” Midwest Art History Society Conference, Cleveland Museum of Art, 7 April 2017. ↩︎

-

Louisa C. Matthew, “‘Vendecolori a Venezia’: The Reconstruction of a Profession,” The Burlington Magazine 144, no. 1196 (November 2002): 680–686. ↩︎

-

For technical analysis on other works by Titian, see Jill Dunkerton et al., “Titian’s Painting Technique before 1540,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 34 (2013); Jill Dunkerton et al., “Titian’s Painting Technique from 1540,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 36 (2015); Jill Dunkerton, “Titian’s Painting Technique,” in Titian, ed. David Jaffé (London: National Gallery, 2003), 46–59; and Susanna Biadene and Filippa Maria Aliberti Gaudioso, Titian: Prince of Painters, exh. cat. (Venice: Marsilio, 1990), 377–400. ↩︎

-

Michel Hochmann, Peintres et Commanditaires à Venise 1540–1628 (Rome: École Française de Rome, 1992), 357–358. ↩︎

-

The script on the Detroit letter is heavily abraded. John Shearman tentatively read “eas Franceschinus… Ma…A…M.D.L.” John Shearman, The Early Italian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 270. As observed by Peter Humfrey, among others, the purported date, 1550, is too late to coincide with the sitter’s actual age or with developments in Titian’s style. On letter-locking systems, see Jana Dambrogio, https://letterlocking.org/categories, accessed 17 May 2022. Jana Dambrogio, telephone communication with author, 27 March 2017. ↩︎

-

By about 1928, the letter depicted in the Clowes portrait was no longer legible, as shown by the photograph associated with the certificates of expertise. This is confirmed in a letter from Arturo Grassi to G.H.A. Clowes, 27 June 1935, File 2016.166 (C10074), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Bill of sale, 5 June 1935, in File C10074, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. According to Grassi, Angela Rossati Bono was a descendant of the sitter and had inherited the portrait by descent. Grassi’s information was later amended by G.H.A. Clowes, who wrote that the painting had been found in the attic of a Venetian army officer; letter from G.H.A. Clowes to E. P. Richardson, 30 March 1950, in File C10074, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Files relating to this dealer were lost after the death of his father, Luigi Grassi, in 1937. Customs stamps on the back of the painting, from 1928 and 1931 respectively, indicate that this painting may have been on the move prior to its sale to G.H.A. Clowes; see Technical Examination Report. ↩︎