Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

Author

Provenance

Galerie Sedelmeyer, Paris, France.19

Eduard Friedrich Weber (1830–1907), Hamburg, Germany, in 1897.20

Marczell von Nemes (1866–1930), Munich, Germany, by 1930.21

Probably Countess Vetter von der Lilie, Vienna, Austria.22

E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York, New York.23

Dr. George Henry Alexander Clowes (1877–1958), Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1934.

Clowes Fund Collection, Indianapolis, Indiana, since 1958, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971.

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields in 2018.

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes, a Memorial Exhibition, no. 56;

Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, South Bend, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 50;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, IN, 1963, Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, no. 17;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at the Newfields, Indianapolis, IN, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection.

References

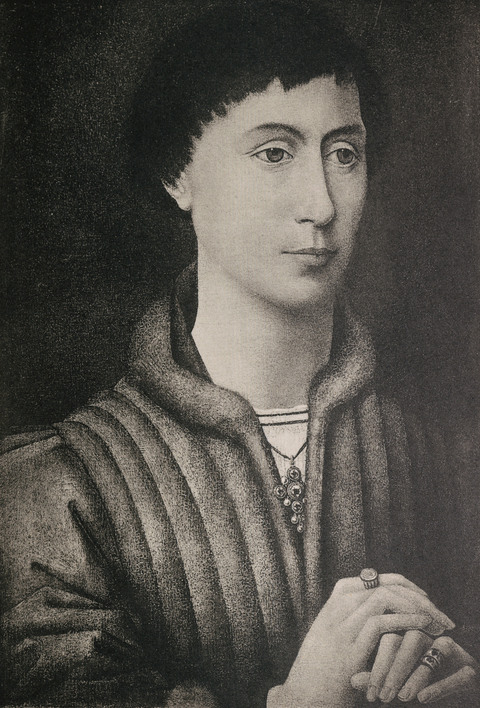

Patricia Bennett, “The Portraiture of Rogier van der Weyden and the Problem of Copies, with a Case Study of Portrait of a Young Man, Clowes Collection, Indianapolis Museum of Art.” MA thesis (Indiana University – Bloomington, 1983), passim (reproduced);

Lorne Campbell, Rogier de le Pasture: Peintre officiel de la ville de Bruxelles; Portraitiste de la cour de Bourgogne, 6 Octobre–18 Novembre 1979, Musée Communal de Bruxelles, Maison du Roi (Brussels: Crédit Communal de Belgique, 1979), 155;

Marin Davies, Rogier van der Weyden: An Essay, with a Critical Catalogue of Paintings Assigned to Him and to Robert Campin (London: Phaidon, 1972), 217.

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 102–3 (reproduced);

Max J. Friedländer, Die altniederländische Malerei: Rogier van der Weyden und der Meister van Flémalle (Berlin: P. Cassirer, 1924); Early Netherlandish Painting: Rogier van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle (Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff, 1967), no. 33 (reproduced);

Georges Hulin de Loo, Exposition de tableaux flamands des XIVe, XVe et XVIe siècles: Catalogue critique (Ghent: A. Siffer, 1902), 7;

Haohao Lu and Annette Schlagenhauff, “Provenance: Follower of Rogier van der Weyden’s Portrait of a Man.” Indianapolis Museum of Art Magazine (Spring 2014): 8–10 (reproduced);

Northern European Painting: The Clowes Fund Collection, exh. cat. (Bloomington: Indiana University Museum of Art, 1963), no. 17;

Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), no. 56;

Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character, vol. 1 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953), 478;

Dirk De Vos, Rogier van der Weyden: The Complete Works, trans. T. Alkins (New York: Abrams, 1999), 410.

Notes

-

On the copying practice, see Dagmar Eichberger and Lisa Beaven, “Family Members and Political Allies: The Portrait Collection of Margaret of Austria,” The Art Bulletin 77, no. 2 (1995): 226–28; and Joanna Woodall, “An Exemplary Consort: Antonius Mor’s Portrait of Mary Tudor,” Art History 14, no. 2 (1991): 204. ↩︎

-

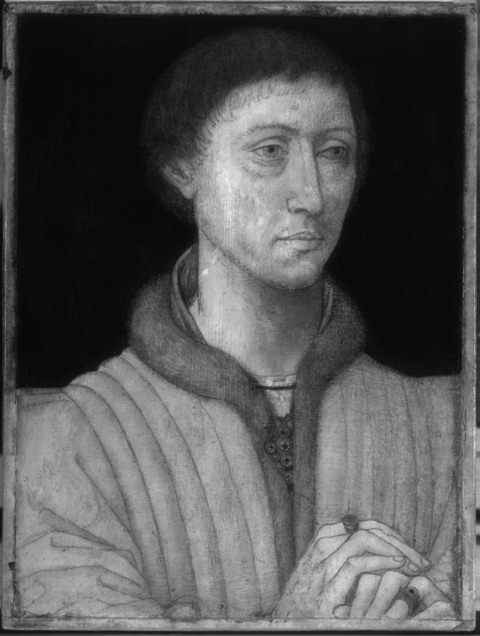

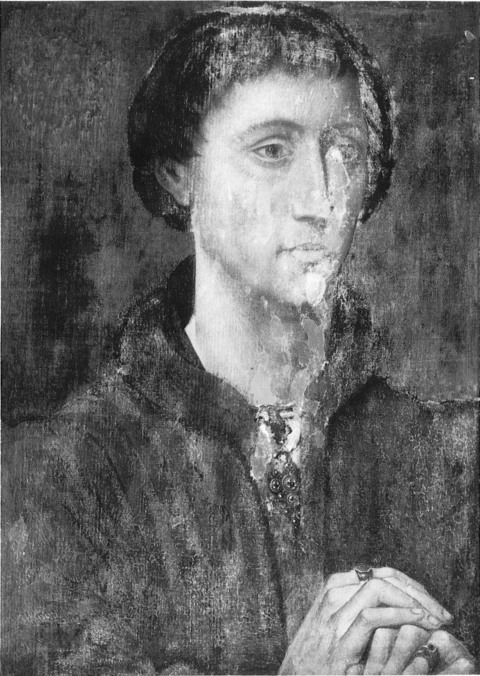

Max J. Friedländer opined that the Cardon portrait, like the Portrait of a Man at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, made “serious and successful” claims to being an original by Rogier. “Von den Männerporträts machen zwei ernstlich und erfolgreich Anspruch darauf, für Originale des Meisters gehalten zu werden: das Bildnes eines Mannes in mittleren Jahren, ausgestellt als ‘Pierre Bladelin’—wohl mit Unrecht, die Ähnlichkeit mit dem Donatorenbildnis in Berlin ist nicht groß—aus der Sammlung R. v. Kaufmann, und das ganz und gar verputzte Porträt eines jüngeren Herrn aus dem Besitz des Herrn Ch. L. Cardon in Brüssel.” See “Die Brügger Leihausstellung von 1902,” Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft 26 (1903): 71. On the restorations, see letter of Lorne Campbell (25 March 1982) to Patricia Bennett, reproduced in the latter’s 1983 MA thesis, “The Portraiture of Rogier van der Weyden and the Problem of Copies, with a Case Study of Portrait of a Young Man, Clowes Collection, Indianapolis Museum of Art.” Copy of thesis available at the Herman B. Wells Library of Indiana University – Bloomington. Nonetheless, according to Friedländer’s notation, “Agnew / pr.[äsentiert] VIII. 45,” on the back of a photograph of the Cardon painting, he received the photograph from Agnew’s Gallery in August 1945. https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/104196. ↩︎

-

See letter of Lorne Campbell (25 March 1982) to Patricia Bennett, reproduced in the latter’s 1983 MA thesis, “The Portraiture of Rogier van der Weyden and the Problem of Copies, with a Case Study of Portrait of a Young Man, Clowes Collection, Indianapolis Museum of Art.” Copy of thesis available at the Herman B. Wells Library of Indiana University – Bloomington. ↩︎

-

“Ehemals v. Hollitscher (?) / Photo stammt aus K.[aiser] F.[riedrich] M.[useum] / Wo jetzt? / = Cardon - Kleinberger (?)” See the webpage of the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie (BD/RKD - ONS/Photo-archive M.J. Friedländer, img.nr. 0000112028) https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/232913. ↩︎

-

Die Gemälde-Sammlung des Herrn Carl von Hollitscher in Berlin: Herausgegeben von Wilhelm Bode und Max J. Friedländer (Berlin: Meisenbach, Riffarth, 1912). ↩︎

-

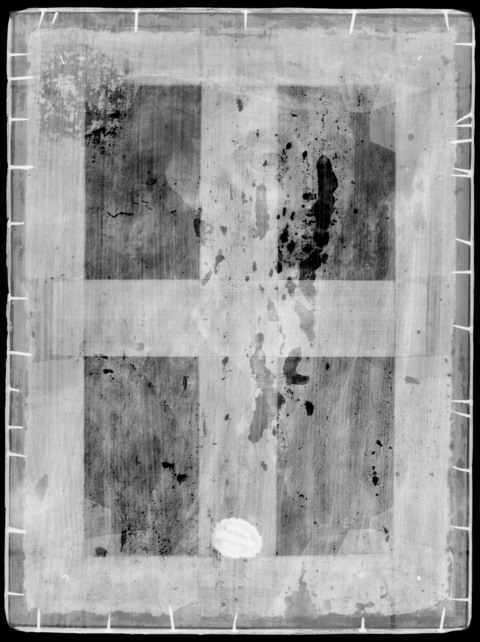

The Clowes portrait was transferred from wood panel to canvas, possibly in the late nineteenth century. Such a treatment was likely unique among the trio, as we know that at least the Cardon portrait remains on wood panel. ↩︎

-

Lorne Campbell, Rogier de le Pasture: Peintre officiel de la ville de Bruxelles; Portraitiste de la cour de Bourgogne, 6 Octobre–18 Novembre 1979, Musée Communal de Bruxelles, Maison du Roi (Brussels: Crédit Communal de Belgique, 1979), 155. ↩︎

-

François van Dycke, Recueil héraldique, avec des notices généalogiques et historiques sur un grand nombre de familles nobles et patriciennes de la ville et du franconat de Bruges (Bruges: C. de Moor, 1851), 446. ↩︎

-

Traittié de la forme et devis comme on fait les tournois, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS. Fr. 2692, fols. 4v–5r. See also Maximiliaan P. J. Martens, Lodewijk van Gruuthuse: Mecenas en Europees Diplomaat ca. 1427–1492 (Bruges: Stichting Kunstboek, 1992), 99. ↩︎

-

On the Van Themseke family, see J. Gailliard, Bruges et le Franc ou leur magistrature et leur noblesse: Avec des données historiques et généalogiques sur chaque famille, unique volume supplément (Bruges: E.D.W. Gailliard, 1864), 21–30. On the deeds of Louis and Daniel van Themseke, see J. Gailliard, Bruges et le Franc ou leur magistrature et leur noblesse: Avec des données historiques et généalogiques sur chaque famille, vol. I (Bruges: J. Gailliard, 1857), 203. ↩︎

-

See letter of Lorne Campbell (25 March 1982) to Patricia Bennett, reproduced in the latter’s 1983 MA thesis, “The Portraiture of Rogier van der Weyden and the Problem of Copies, with a Case Study of Portrait of a Young Man, Clowes Collection, Indianapolis Museum of Art.” Copy of thesis available at the Herman B. Wells Library of Indiana University – Bloomington. According to the RKD, the notation reads: “vNemes / XII.30 Photo / pr.[äsentiert]” [Photo received from Von Nemes December. (19)30]. https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/232912. ↩︎

-

See letter of Lorne Campbell (25 March 1982) to Patricia Bennett, reproduced in the latter’s 1983 MA thesis, “The Portraiture of Rogier van der Weyden and the Problem of Copies, with a Case Study of Portrait of a Young Man, Clowes Collection, Indianapolis Museum of Art.” Copy of thesis available at the Herman B. Wells Library of Indiana University – Bloomington. See also https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/232912. ↩︎

-

“III. 34 ansch.[einend] dass.[elbe] G.[emälde] / Hand[lung] Silbermann, / Wien, / mir orig[inal] von / Wendland gezeigt. / Auf leinwand. / v. Eigenberger restau- / riert. / Identität schwer / nachweisbar, aber / doch sicher” [March 34 likely the same painting / Dealer Silbermann (sic) / Vienna / painting shown to me by / Wendland / on canvas / restored by Eigenberger / identity difficult to prove / yet certain.] https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/232912. Max J. Friedländer, Die altniederländische Malerei: Rogier van der Weyden und der Meister van Flémalle (Berlin: P. Cassirer, 1924); Early Netherlandish Painting: Rogier van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle (Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff, 1967), no. 33. The Clowes portrait, reproduced in both editions, is given the wrong provenance of having been among the collection of Charles-Léon Cardon. ↩︎

-

The phrase is used by Dirk De Vos. See Dirk De Vos, Rogier van der Weyden: The Complete Works, trans. T. Alkins (New York: Abrams, 1999), 410. ↩︎

-

“La composition, la dessin du cou et des mains rappellent Roger. Mais l’oeuvre a trop suffert pour que nous osions nous prononcer.” See Jules Destrée, Roger de la Pasture van der Weyden (Paris and Brussels: G. van Oest, 1930), 179. On the dating, see George Hulin de Loo, “Rogier van der Weyden,” Biographie nationale, académie royale des sciences, des lettres, et des beaux-arts de Belgique (Brussels: E. Bruylant, 1938), 239. ↩︎

-

Handwritten note dated 20 October 1947, Amsterdam, File C10085 (2018.27), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. His assessment would have likely been based on the photograph provided to him by Angew’s Gallery in 1945. See note 2. ↩︎

-

Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character, vol. 1 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953), 478. ↩︎

-

“Eine sehr bedeutende, edel, stilvolle und charakteristische Arbeit von Roger van der Weyden;” “die formen der Hände.” Expertise by Glück and Eigenberger, 6 March 1934, File C10085 (2018.27), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

A red oval wax seal on the stretcher bar can be deciphered to read “Galerie Sedelmeyer Paris.” ↩︎

-

A paper label, once on the verso of the painting, bears a round ink stamp which can be deciphered to read “Galerie Weber, Hamburg.” It also bears the hand-written date “1897” as well as the inventory number “969.” Eduard Weber did not own a gallery but amassed a large and important private collection which he called the Galerie Weber. This painting is not included in any of the catalogues published posthumously in Berlin in 1912. However, correspondence in June 2013 with Carla Schmincke, author of the 2004 Hamburg University dissertation “Sammler in Hamburg: Der Kaufmann und Kunstfreund Konsul Eduard Friedrich Weber (1830–1907),” revealed that in an unpublished inventory of Weber’s collection, which she viewed in 2000 in the possession of a Weber heir, since deceased, nos. 967 to 971 were all purchased at Charles Sedelmeyer’s Gallery in Paris. ↩︎

-

Friedländler was very familiar with the Von Nemes collection; he wrote the introduction to the 1931 posthumous auction collection catalogue as well as an obituary in Pantheon 7 (1931): 32. ↩︎

-

Art historians who documented the Clowes Collection in 1968 (Mark Roskill, unpublished manuscript in IMA Archives) and in 1973 (A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection, Indianapolis Museum of Art) both note that the painting came through Silberman Galleries from Countess Vetter von der Lilie, Vienna, but this has not been corroborated. A customs stamp on the stretcher bar reads “Bundesdenkmalamt Wien,” indicating that painting did pass through Vienna where the Silberman brothers had a gallery. ↩︎

-

Bill of sale from A. Silberman, 6 October 1934, File C10085 (2018.27), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎