Overview

Accession number: 2009.52

Artist: Badia a Isola Master

Title: Madonna and Child

Materials: Egg tempera (untested) and gilding on poplar panel

Date of creation: About 1300–1310

Previous number/accession number: C10031

Dimensions: 63.5 × 54.2 cm

Conservator/examiner: Fiona Beckett and Roxane Sperber

Examination completed: 2016, revised 2020

Distinguishing Marks

Front:

None

Back:

None

Summary of Treatment History

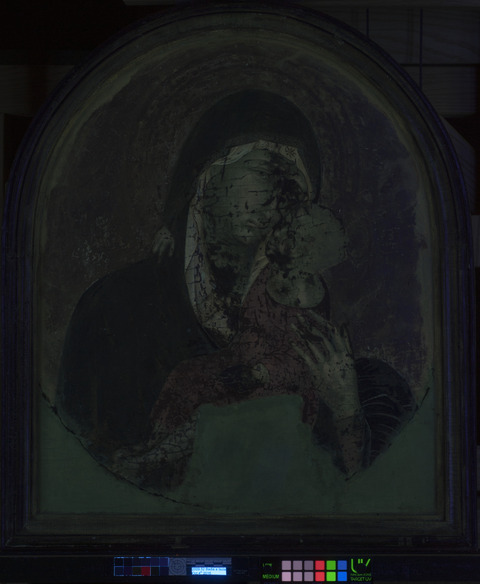

It is almost certain that the work belonged to a larger altarpiece, which, as with so many early Italian altarpieces, was disassembled and its sections sold as individual paintings. It has been significantly altered with age. The exact chronology is uncertain, but several images of the painting over time give clues to its evolution. A photograph published in 1936 but taken at an earlier date shows the work with the hand, arm, and robes of the Madonna intact (tech. fig. 1). It is unclear if this image shows the panel before it was trimmed to remove the lower section of the composition, or if it pictures the work with a reconstruction of the Madonna’s hand, arm, and robes. Notably, the work is shown with what appears to be a section of the original engaged frame extending down the sides of the panel.

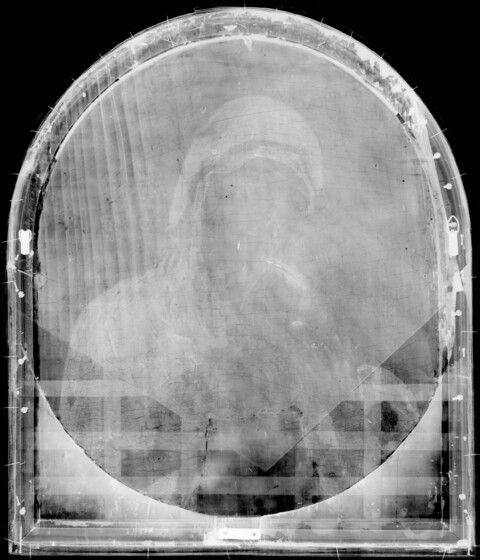

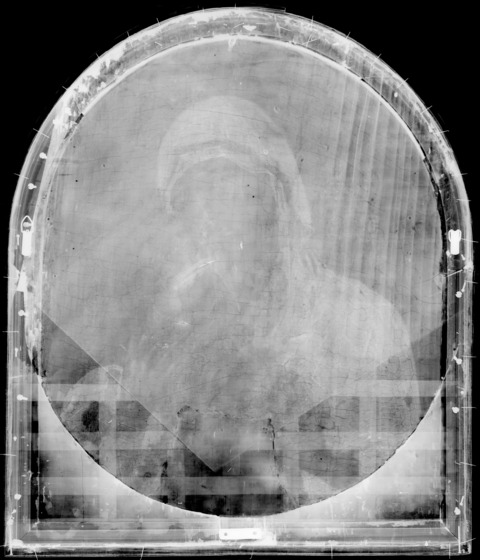

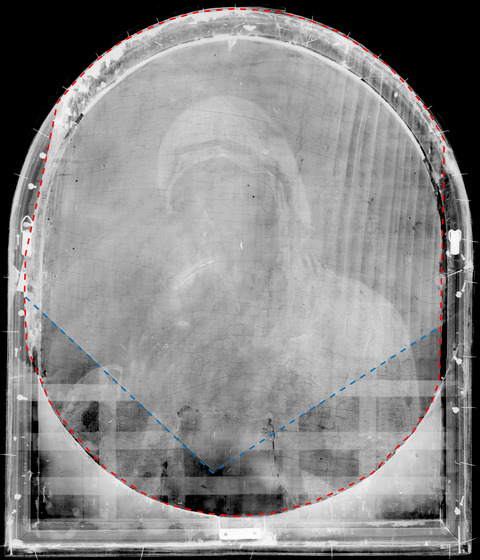

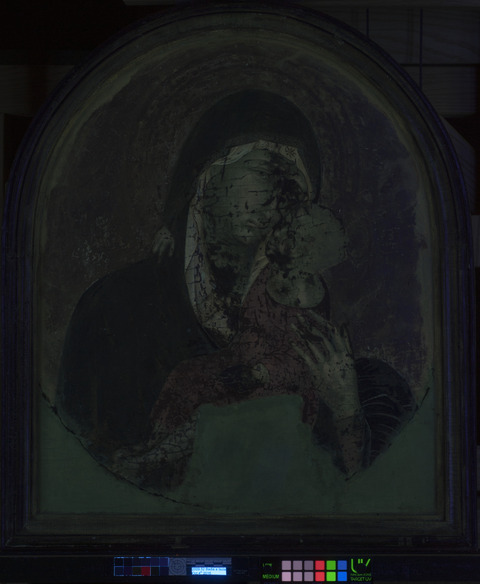

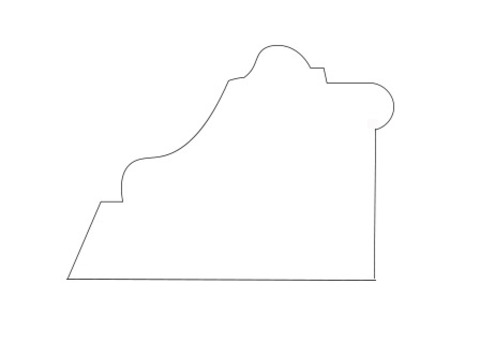

Perhaps due to structural instability of the wood, the lower portion of the original support was removed by cutting the painting into an oval (see tech. fig. 4). It is unclear how long it retained this shape, but by 1935 an addition had been added to the bottom of the panel, creating the shape that it still retains. During this intervention, part of the original support was thinned (see tech. fig. 8), and a cradle was attached to join the addition to the original support (see tech. fig. 9).

During a treatment that appears to have been carried out in 1935, canvas and fill were added to extend the paint layer on the front of the panel, perhaps in an attempt to mimic the techniques of early Italian painting. Technical figures 2 and 3 are both dated 1935 and appear to show this process under way. Technical figure 2 shows the panel with the canvas applied but without fill or retouching. Technical figure 3 shows the painting, much in its current state, with fill and neutral retouching. This approach was likely taken because a large-scale reconstruction was deemed less ethical than the application of a single swatch of color. No further documentation has been retained for these interventions.

Documentation indicates a series of condition assessments and treatments were carried out on the collection around the time the works were moved from the Clowes residence to the IMA in 1971. A condition report by Paul Spheeris in October of that year, likely carried out before the paintings were relocated, described the painting as “O.K. but frame broke at left side.” He recommended that the painting receive immediate attention, presumably due to the broken frame.1

A second condition assessment was carried out upon arrival of the paintings at the IMA. This assessment described the work as in “relatively stable condition” but having a “coat of discolored natural resin varnish which masqued [sic] the original concept of the artist.” The painting was examined using ultraviolet light, and an X-radiograph of the painting was made.2 These examinations revealed that areas of inpainting covered the artist’s original paint and thus it was decided that the painting would be cleaned.3 No treatment report from this treatment has been retained.

The condition of the painting was documented in the Clowes Collection annual survey from 2011 to 2020.

Current Condition Summary

Structurally, the painting is in stable condition. Aesthetically, the painting suffers from numerous losses and abrasions. The greenish appearance of the Madonna’s face is due to severe abrasion of the upper layers of paint, which would have been applied over the green verdaccio layer, leaving the verdaccio exposed. The fill in the lower addition to the painting is slightly cracked and lifting where it meets the original paint layer. A green color was chosen for the neutral retouching that was used on the fill, presumably to imply a verdaccio layer. However, verdaccio would have traditionally been reserved for skin tones, and its presence in the lower section of the painting is unusual and distracting. This could be remedied with a conservation treatment to present a more accurate representation of the original ground color.

Methods of Examination, Imaging, and Analysis

| Examination/Imaging | Analysis (no sample required) | Analysis (sample required) |

|---|---|---|

| Unaided eye | Dendrochronology | Microchemical analysis |

| Optical microscopy | Wood identification | Fiber ID |

| Incident light | Microchemical analysis | Cross-section sampling |

| Raking light | Thread count analysis | Dispersed pigment sample |

| Reflected/specular light | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) |

| Transmitted light | Macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (MA-XRF) | Raman micro-spectroscopy |

| Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UV) | ||

| Infrared reflectography (IRR) | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) | |

| Infrared transmittography (IRT) | Scanning electron microscope -energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) | |

| Infrared luminescence | Other: | |

| X-radiography |

Technical Examination

Description of Support

Analyzed Observed

Material (fabric, wood, metal, dendrochronology results, fiber ID information, etc.):

The original support for the painting is wood panel, identified by dendrochronologist Ian Tyers as Salicaceae, willow/poplar.4 The grain of the panel has a vertical orientation. The panel was likely part of a larger altarpiece that has been dismantled.

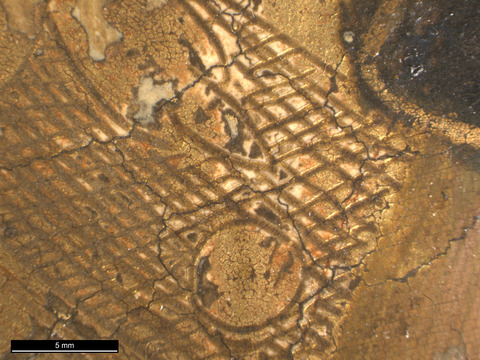

The X-radiograph reveals continuous wood grain through the original panel to the top of the frame (tech. fig. 4). However, a gap along the top edge of the panel is visible where it meets the frame, and the canvas that was applied to the front of the panel appears to wrap around the edge under the engaged frame. This suggests that the extant segments of the original frame were carved separately from the panel and attached to it after the addition of the canvas, but before the application of gesso and gilding. The bottom member of the current frame, and the lower components on either side, appear to be nonoriginal (tech. figs. 4, 9). The lower portions are entirely reconstructed, as evident from the back and the X-radiograph. Canvas has also been applied to the lower portion of the panel, including over nonoriginal wood. Although it is difficult to determine with certainty, it appears that this canvas was added later to match that of the original portion of the panel.

The original shape of the engaged frame, which only existed as an arch at the top of the panel, is visible in an archival image of the painting (see tech. fig. 1). This was a common design for polyptychs. The arched frame and the Madonna and Child subject matter are typical in central panels of thirteenth-century Italian altarpieces. For example, the Duccio di Buoninsegna altarpiece at the Pinoteca Nazionale in Siena depicts a similar Madonna and Child in the central panel (tech. fig. 5).

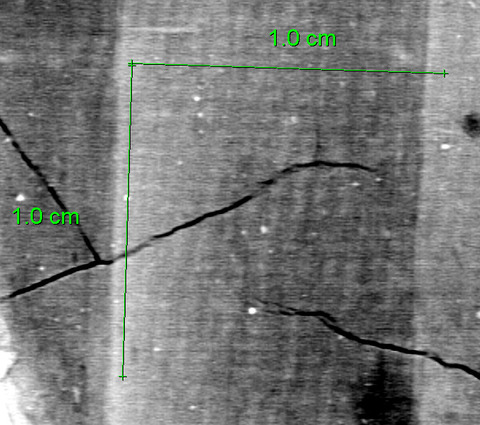

A finely woven, plain-weave canvas (approximately 18 × 17 threads/cm) (tech. fig. 6) covers the panel and frame. Examination of the top edge of the panel suggests the canvas extends under the carved component of the wooden frame and wraps around the top edge of the panel. The engaged component of the frame appears to have been separately covered with canvas. An additional section of canvas was added to the frame addition, in keeping with the Italian fabrication methods that would have been used when the panel was first created (see tech. fig. 2). This added section of canvas also wraps around the outer edges of the engaged frame and was clearly added during a conservation campaign. Along the edges, the canvas that was added later appears to have a white gesso layer and a brown layer of opaque, matte oil paint. This masks other indications of the frame’s construction.

Characteristics of Construction / Fabrication (cusping, beveled edges of panels, seams, joins, battens):

The painting was constructed from a single wooden panel. The lack of warp indicates that it was likely a radial, or close to radial, cut of wood. A wooden dowel is visible on the upper-left edge in the X-radiograph and is likely a fill from the panel-preparation process. Hand-tooling can be seen on the back of the original panel.

Thickness (for panels or boards):

The board is approximately 6 cm thick, including the engaged frame. This dimension varies slightly depending on the location.

Production/Dealer’s Marks:

None

Auxiliary Support:

Original Not original Not able to discern None

The auxiliary support is not original to the painting and consists of a partial cradle that is attached to the thinned section of the back as well as the added support (tech. figs. 7, 8, 9). The cradle consists of seven vertical members fixed in place and three horizontal members, also fixed. The cradle is cut to fit the diagonal thinning of the panel and create support for the added lower reconstruction. The central vertical member has been partially removed.

Condition of Support

The support is in stable condition, although it has suffered significant damages in the past. The back shows extensive tunneling from wood-boring insects. Prior to the addition of the partial cradle, the thickness of the original panel was thinned, revealing the insect tunnels in cross section. The panel was deliberately cut into an oval (tech. fig. 7) and then thinned into a “v” shape on the back (tech. fig. 8), likely to accommodate the addition of the cradle or possibly to remove a particularly damaged area of the support. The thinned area where the cradle is attached (see purple in diagram) does not appear to have as much woodworm damage as the upper section of the panel, which may suggest the cradle was added to this area because it was the most stable. Losses are present along the outer edges of the original panel due to the woodworm infestation and damages inflicted over time and through natural aging.

Description of Ground

Analyzed Observed

The ground appears to be a thick, white, calcium-based ground, likely gesso, as would have been typical of Italian panel-preparation techniques in the fourteenth century. Most likely two layers of ground are present (a gesso grosso followed by a gesso sottile), although more analysis is necessary to confirm this. A layer of canvas can be seen in the X-radiograph and covers the panel prior to the application of the ground.

Materials/Binding Medium:

The calcium-containing ground layer was likely bound with animal-skin glue, but this has not been confirmed through analysis.

Color:

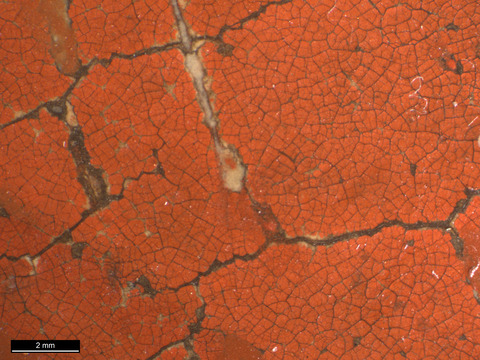

White was employed for the initial ground layers (tech. fig. 10), and a green verdaccio layer was subsequently applied to the areas beneath the skin tones. An orange-red bole layer is visible under the gilding, as previously mentioned.

Application:

The ground was likely brush applied and sanded smooth, as would have been common practice.

Thickness:

The ground is quite thick. This thickness was required to cover the canvas texture and prepare the panel for gilding and painting with egg tempera.

Sizing:

The panel would likely have been sized prior to the application of the canvas layer, as well as to assist in adhering the canvas to the underlying wooden support.

Character and Appearance (Does texture of support remain detectable / prominent?):

Neither the canvas nor the wood-grain texture is visible through the thick ground and paint layers.

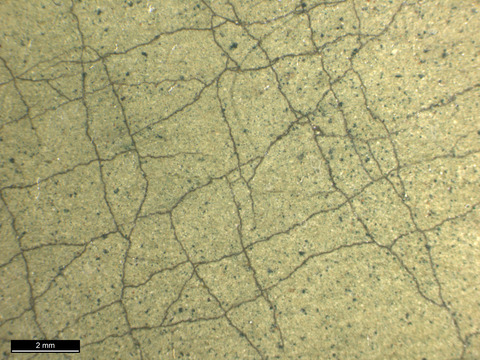

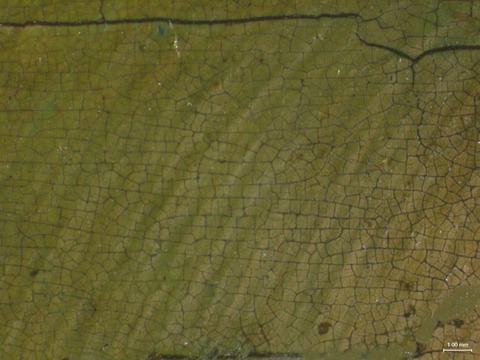

Condition of Ground

The ground layer is in stable condition but has suffered numerous losses. A natural craquelure pattern, due to aging, can be seen over the surface of the painting in a slightly horizontal pattern, even though the panel grain runs vertically. This may be a result of the canvas layer offsetting the stresses caused by movement in the panel. Where the bottom of the panel was removed, the added panel has been covered with a canvas layer and coated with a thick layer of fill to imitate the ground layer (tech. fig. 11). Neutral retouching in green paint was applied to imitate the verdaccio layer. The choice of green is somewhat unusual for such a large section, as that color was primarily used underneath skin tones.

Description of Composition Planning

Methods of Analysis:

Surface observation (unaided or with magnification)

Infrared reflectography (IRR)

X-radiography

Analysis Parameters:

| X-radiography equipment | GE Inspection Technologies Type: ERESCO 200MFR 3.1, Tube S/N: MIR 201E 58-2812, EN 12543: 1.0mm, Filter: 0.8mm Be + 2mm Al |

|---|---|

| KV: | 25 |

| mA: | 3 |

| Exposure time (s) | 180 |

| Distance from X-ray tube: | 36″ |

| IRR equipment and wavelength | Opus Instruments Osiris A1 infrared camera with InGaAs array detector operating at a wavelength of 0.9–1.7µm. |

Medium/Technique:

There appears to be some outlining in a fluid carbon-containing medium around the Madonna’s figure (tech. fig. 12). Some smaller dots are present along some of the clothing folds but not with enough consistency to indicate the use of pouncing from a cartoon transfer. The devotional Madonna and Child composition was a very common subject in thirteenth-century Italian artwork, and while there is no direct evidence of the artist working from a design, it is highly likely that this method was employed. It would have also been necessary to plan where the gold leaf would be applied, as these areas were typically covered initially with several layers of red bole. Notably, there are no visible incision lines delineating the edge of the water gilding and paint layer as are often found on paintings of this period.5

Pentimenti:

No pentimenti are visible in the painting using IRR; however, minor outlines and adjustments are visible along the contours of the Madonna’s face and drapery (tech. fig. 13), as well as in the feet of the Christ child.

Description of Paint

Analyzed Observed

Application and Technique:

Water gilding

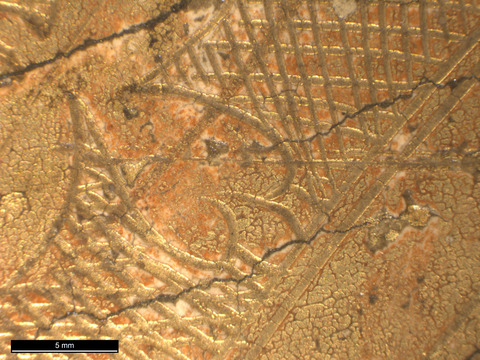

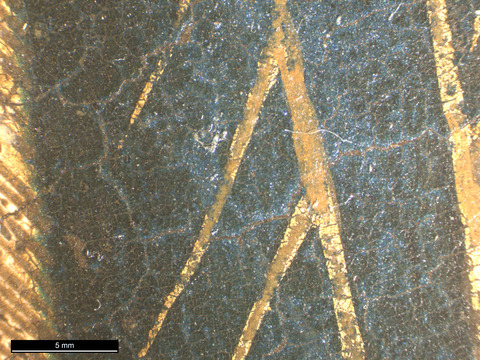

After establishing the composition, a red bole layer was applied to the areas where water gilding would be applied to create the fondo oro. This colored bole created an orange-red hue to the gold. The gold leaf was then applied to this area and burnished. Hand-drawn designs using an intaglio technique were applied in the halos around both figures (tech. figs. 14, 15).

Paint layer

Once gilding was complete, the paint layer was applied using a fine brush. A green verdaccio layer was applied beneath the areas of skin (tech. fig. 16). This was a common practice of early Italian artists in order to temper the bright pink appearance of the skin.

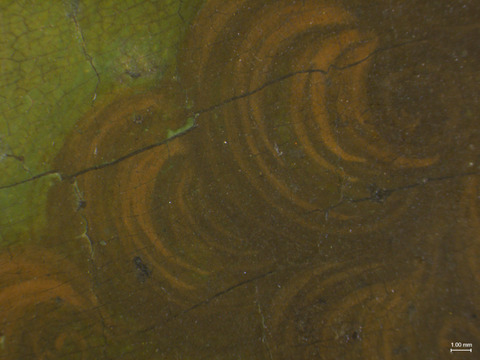

The paint for the skin was applied using small linear brushstrokes (tech. fig. 16), typical of egg tempera painting. Shades of pink were applied in thin, delicate brushstrokes to create form in the faces and hands. Bright white highlights are present at the corner of the Madonna’s mouth and along the top of her lip (tech. fig. 17).

The areas of drapery and the child’s hair were applied in flat swathes of color and extend slightly over the boundary of the water gilding in most areas. The red robes of the Christ child and his hair were later detailed using a small brush with a different paint color (tech. fig. 18). Golden curls were articulated in the hair, and a deep red paint was used to outline the gently falling robes.

Forms in the Madonna’s robes were created through the application of mordant gilding in the final stages of the painting process (tech. fig. 19). This created lines of drapery as well as decoration on the borders of her robe and headdress (tech. fig. 20).

Painting Tools:

The painting was executed with small, fine brushstrokes using a small brush.

Binding Media:

The binding media is likely egg tempera, but this has not been tested.

Color Palette:

The color palette is relatively simple, with blue for the Madonna’s robe, red for the Christ child’s robe, and white in the garments around the Madonna’s head and in her skin tones. (Her skin now appears greenish in hue due to transparency and abrasion over time, revealing the verdaccio layer.) XRF analysis was completed in several areas of the painting (tech. fig. 21, table 1), and the results indicate that the artist used azurite for the blues; vermilion for the red tones (possibly also red lead, as would have been common during this time); and lead white in many areas of the painting, including the skin tones and the white garment. The strong peak for iron in the verdaccio layer suggests the use of terre verde in this passage, as would have been typical. There is a trace presence of copper, which could indicate the use of malachite, however the trace is so small that it is unlikely to be the primary pigment used to create the strong green paint. However, in the large area of restoration along the bottom, chromium and zinc were found, indicative of contemporary applied pigments (likely nineteenth century). As suspected, gold was found in the gilding. Strontium was detected in small amounts, which is sometimes present in calcium sulfate that is used in the ground.

XRF Analysis:

| Sample | Location | Elements | Possible Pigments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pink in cheek area of Madonna figure | Major: Pb Minor: Hg, Fe Trace: Ca, Cu, Sr | Lead white, vermilion, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium (likely from ground layer), trace of copper-containing green and/or blue pigment. |

| 2 | Green tone in neck of Madonna figure | Major: Pb, Fe, Ca Minor: Trace: Sr, K, Cu, Hg, Mn | Iron silicate (green earth), iron oxide (earth pigments, including umber), lead white, trace of vermilion, trace of calcium (likely from ground layer), trace of copper-containing green and/or blue pigment. |

| 3 | Blue in robe of Madonna figure (head) | Major: Cu Minor: Pb, Ca, Fe Trace: K, Ba | Copper-containing blue pigment (likely azurite), lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), calcium (likely from ground layer), trace of barium (likely from retouching materials). |

| 4 | Gold in halo of Madonna figure | Major: Au, Fe, Ca Minor: Sr Trace: Pb, K, Ti | Gold (from gilding), iron oxide (likely from orange-red bole), calcium (likely from ground layer), trace of lead white. |

| 5 | Red in Christ child’s robe | Major: Hg Minor: Pb Trace: Ca, Fe, Cu, K | Vermilion, lead white and/or red lead, trace of calcium (likely from ground layer), trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of copper-containing green and/or blue pigment. |

| 6 | Green area of restoration in center | Major: Ca Minor: Fe, Cr Trace: Pb, Zn, Sr, K | Calcium (likely from fill), chromium-containing green, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of lead white, trace of zinc (likely zinc white). |

| 7 | Christ child eye | Major: Pb Minor: Fe, Trace: Ca, Sr, K, Cu, Mn | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium (likely from ground layer), trace of copper-containing green and/or blue pigment. |

Table 1: Results of X-ray fluorescence analysis conducted with a Bruker Artax microfocus XRF with rhodium tube, silicon-drift detector, and polycapillary focusing lens (~100μm spot).

*Major, minor, trace quantities are based on XRF signal strength not quantitative analysis

Surface Appearance:

The surface exhibits little texture. Small, crosshatched brushstrokes (tech. fig. 16), consistent with that of egg tempera painting, are visible. There are no areas of impasto or heavier application of paint. The fondo oro shows the design applied to the gold leaf in the halos with intaglio design.

Condition of Paint

The paint layer is in stable condition but suffers from significant past damage as well as natural aging. A distinct craquelure network is present throughout the painting. Retouching is present in copious amounts across the surface the painting, including in the areas of gilding, which have been restored using gold paint. Much of the retouching is poorly matched and hastily applied (tech. fig. 22).

The varnish appears to adequately saturate the painting, although the gold fondo oro would typically look much more vibrant and reflective than it currently does. The skin tones have increased transparency over time, contributing to the greenish hue in their appearance as they allow more of the underlying verdaccio to become visible. They have also been severely abraded, which has compromised the masterful quality of the original work. This damage is particularly apparent in the Christ child’s face, where few remnants of his proper right eye and mouth remain intact (tech. figs. 22, 23).

A smaller network of age cracking is visible in the red of the Christ child’s robes and could be indicative of a lean-over-fat application of the tempera. An additional cracking network is present in the added restoration elements. The entire lower section of painting has been restored using a neutral retouching approach in a green paint. The border of the restoration-original panel interface has a deep and distracting crack, and some of the fill has lifted slightly.

Description of Varnish/Surface Coating

Analyzed Observed Documented

| Type of Varnish | Application |

|---|---|

| Natural resin | Spray applied |

| Synthetic resin/other | Brush applied |

| Multiple Layers observed | Undetermined |

| No coating detected |

The painting appears to have a coat of synthetic varnish on its surface with residues of an older natural resin varnish, identifiable by a greenish fluorescence when viewed with ultraviolet radiation (tech. fig. 24). The subject of varnishing early tempera paintings remains debatable, and while references to it exist, such as in translations of Cennino Cennini’s Il Libro dell’Arte,6 others indicate it was not a contemporary practice. In either case, it would be difficult to ascertain the original state of the work, as any remnants of an original varnish would have likely been cleaned away during later varnish removal campaigns. Subsequent restorations have resulted in the applications of layers of varnish, overpaint, and retouching. The most recent restoration campaign likely added a varnish layer to create a barrier between original material and retouching.

Technical figure 1 shows a photograph of the painting with the lower section fully reconstructed.7 Photos taken during treatment in 1935 (see tech. figs. 2, 3) show the current intervention under way and the previously reconstructed lower section (see tech. fig. 1) replaced with the current neutral retouching. There are no records of treatment to the object after this 1935 intervention.

Condition of Varnish/Surface Coating

The varnish is in satisfactory condition and imparts neither a bright shine nor too dull of an appearance to the paint layer. The retouching does not match the surrounding paint layers, for example, in the Madonna’s face, and results in some patchy and splotchy areas. Under ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence, the extent of retouching on the painting is evident, as large areas of nonfluorescent paint in the faces and hands block the fluorescence of the underlying varnish layer (tech. fig. 24). The green area of restoration is particularly distracting to the painting and would benefit from a more neutral reintegration via inpainting.

Description of Frame

Original/first frame

Period frame

Authenticity cannot be determined at this time/ further art historical research necessary

Reproduction frame (fabricated in the style of)

Replica frame (copy of an existing period frame)

Modern frame

Frame Dimensions:

Outside frame dimensions: 63.5 × 54.2 × 3 cm

Distinguishing Marks:

None

Description of Molding/Profile:

The painting has an engaged frame that appears to be partly original and partly a later addition (see the Description of Support). Examination of the back of the painting reveals the upper arch of the frame appears to be original; it is pictured in an early photograph of the painting before the additions were made (tech. fig. 1). The frame is carved wood that has been covered in gesso with red bole and water gilding. The additions closely match the profile of the original frame (tech. fig. 25).

Condition of Frame

Both original and additions to the frame are in good aesthetic condition and are structurally stable.

Notes

-

Paul A.J. Spheeris, “Conservation Report on the Condition of the Clowes Collection,” 25 October 1971, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Martin Radecki, Clowes Collection condition assessment, undated (after October 1971), Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Martin Radecki, Clowes Collection condition assessment, undated (after October 1971), Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Ian Tyers, “Tree-Ring Analysis and Wood Identification of Paintings from the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” Dendrochronological Consultancy Report 1082, January 2019, p. 32. Conservation Department files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini’s description of early Italian painting technique includes marking the outlines of the figures with incision lines. It should be noted, however, that Cennini was writing nearly a century after this work was likely created. Cennino Cennini, Il Libro dell’Arte (The Craftsman’s Handbook), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (Dover: New York, 1960), 76. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, Il Libro dell’Arte (The Craftsman’s Handbook), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (Dover: New York, 1960), 91–94 (egg tempera painting), 98–100. ↩︎

-

This image was published in 1936 but is almost certainly from an earlier date. Photos from 1935 taken during treatment show the painting without neutral retouching on the reconstructed lower section. ↩︎

Additional Images