Overview

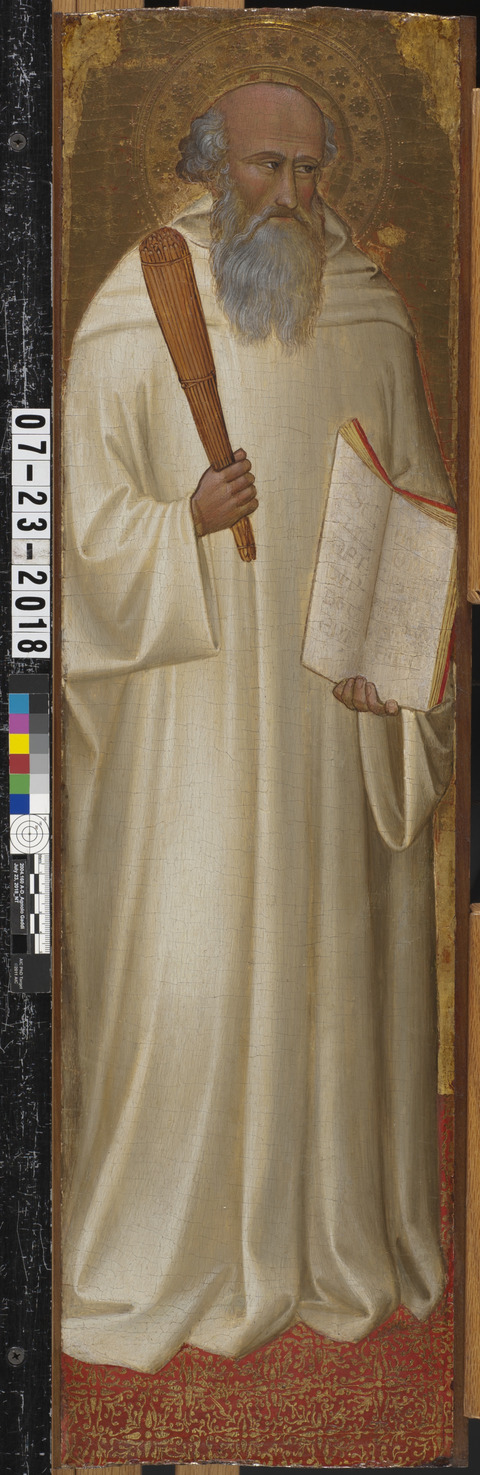

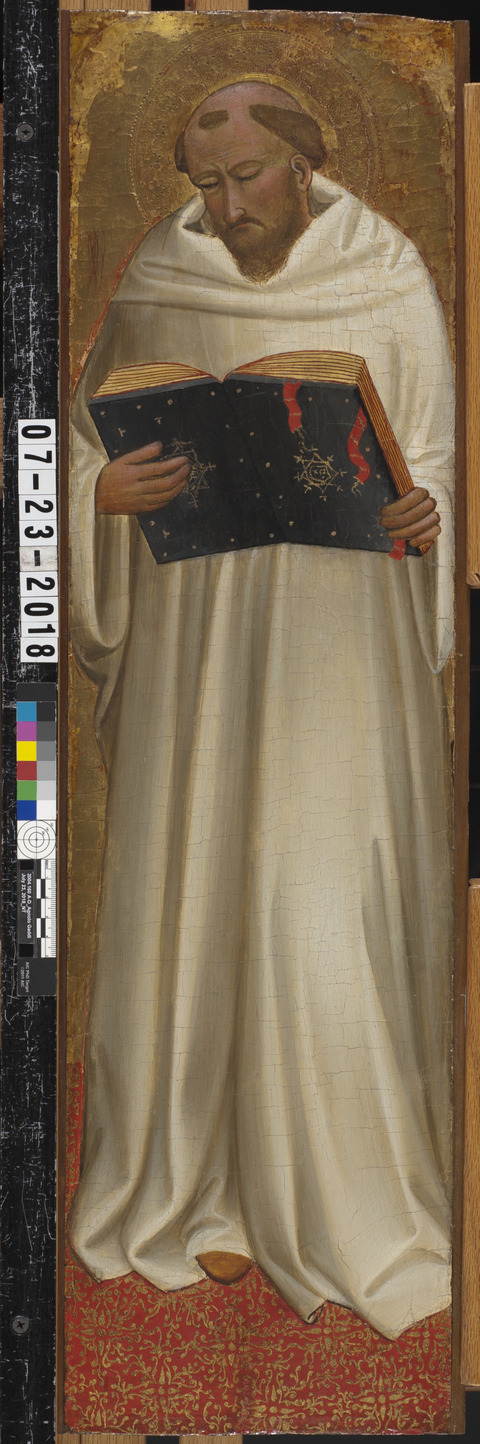

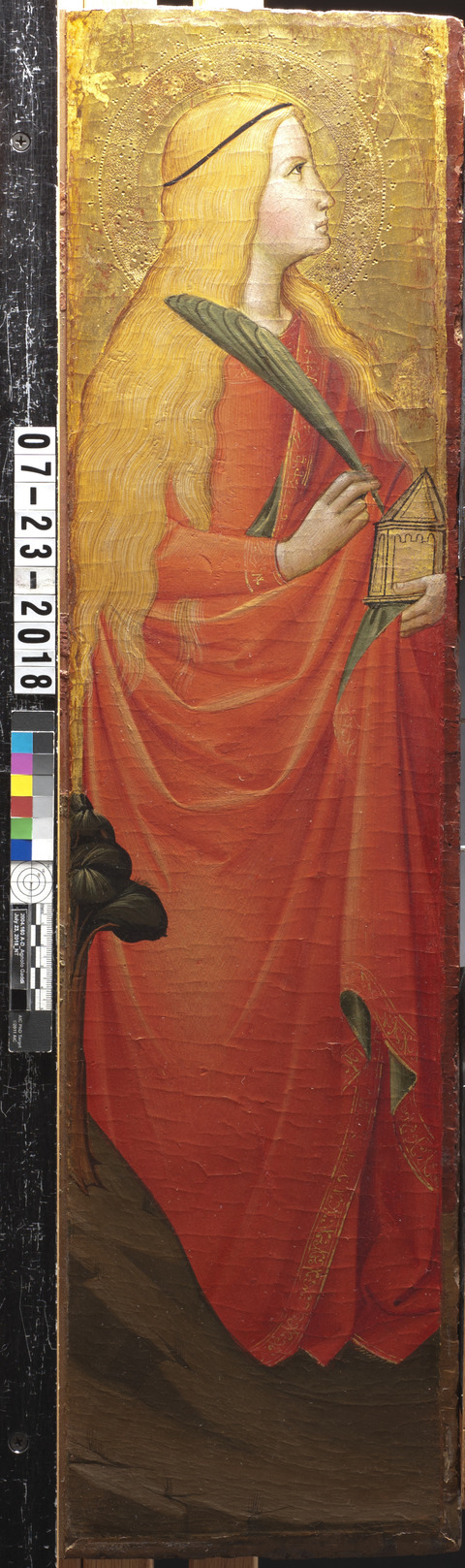

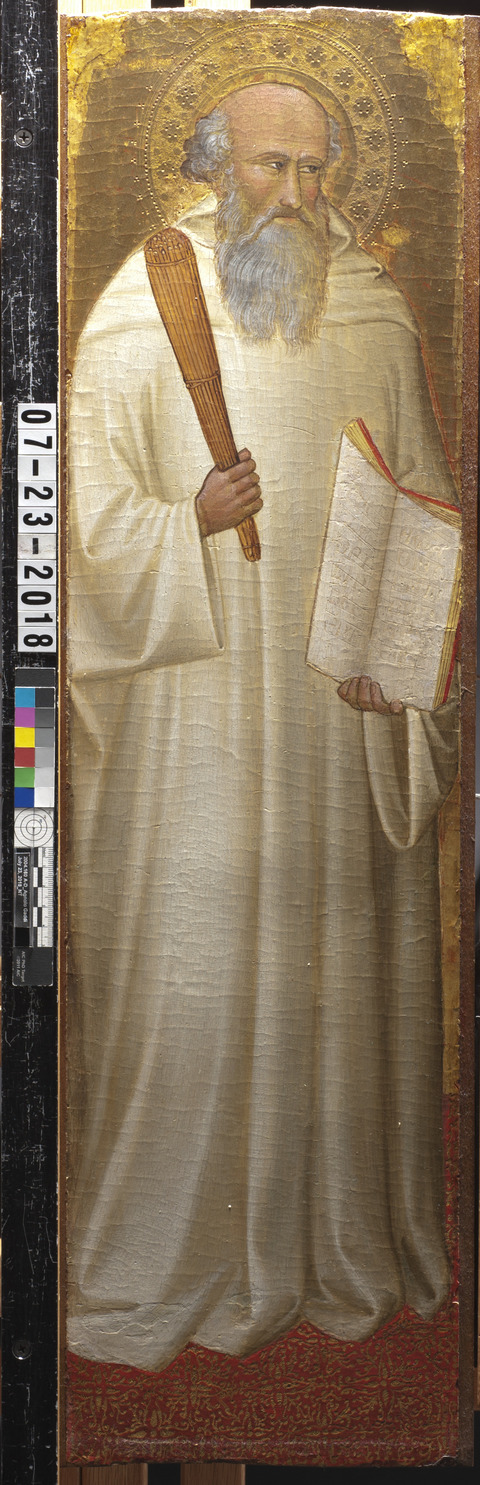

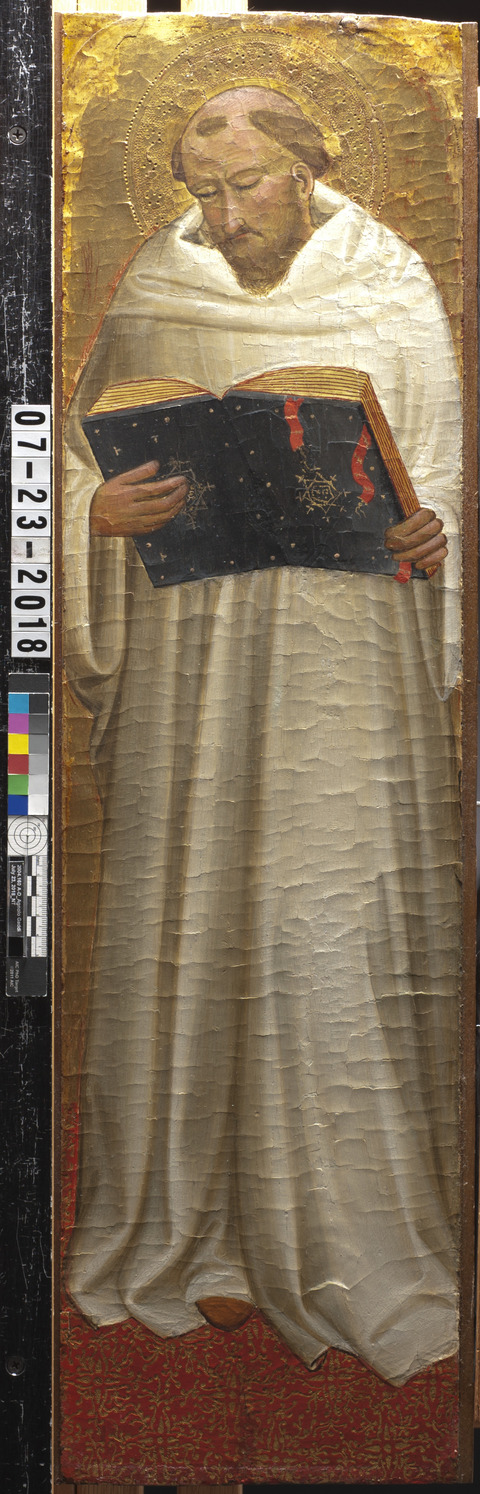

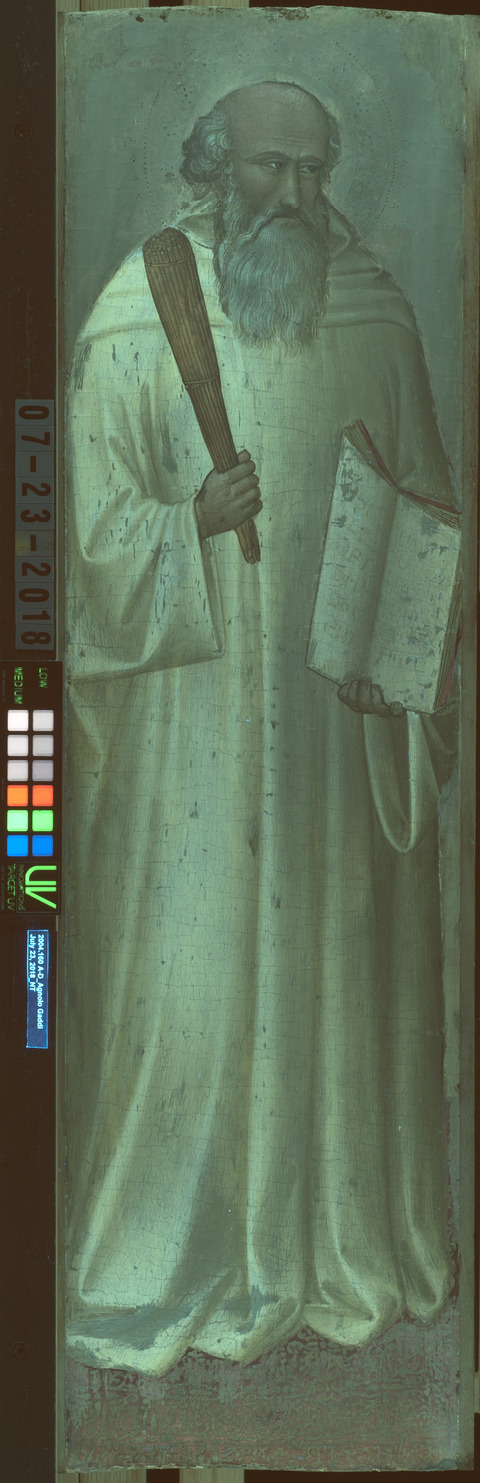

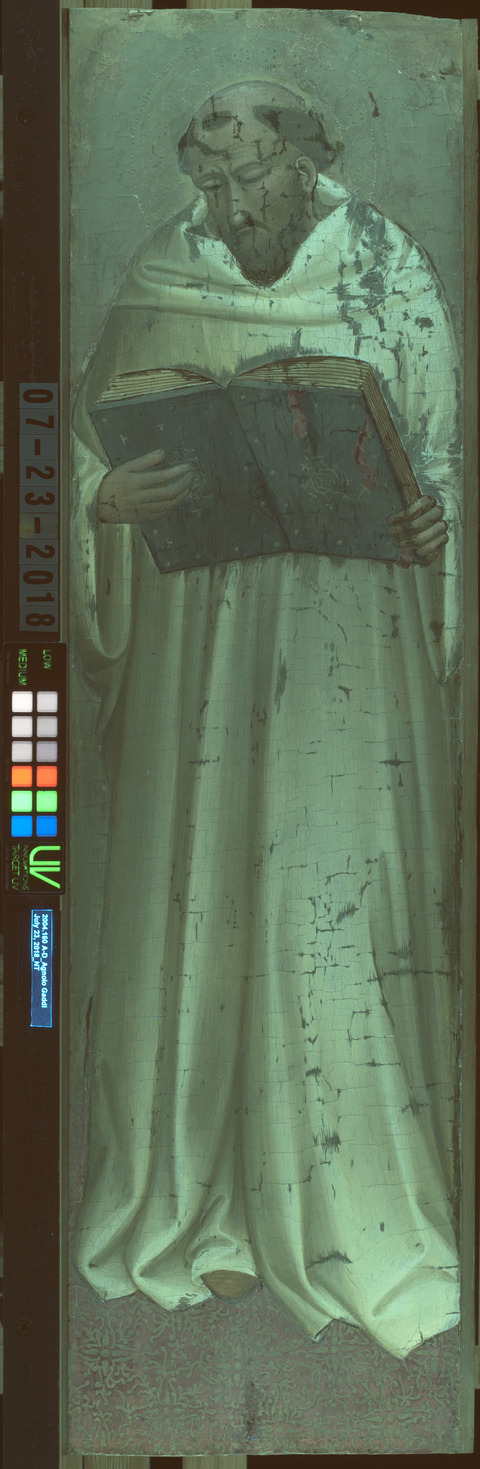

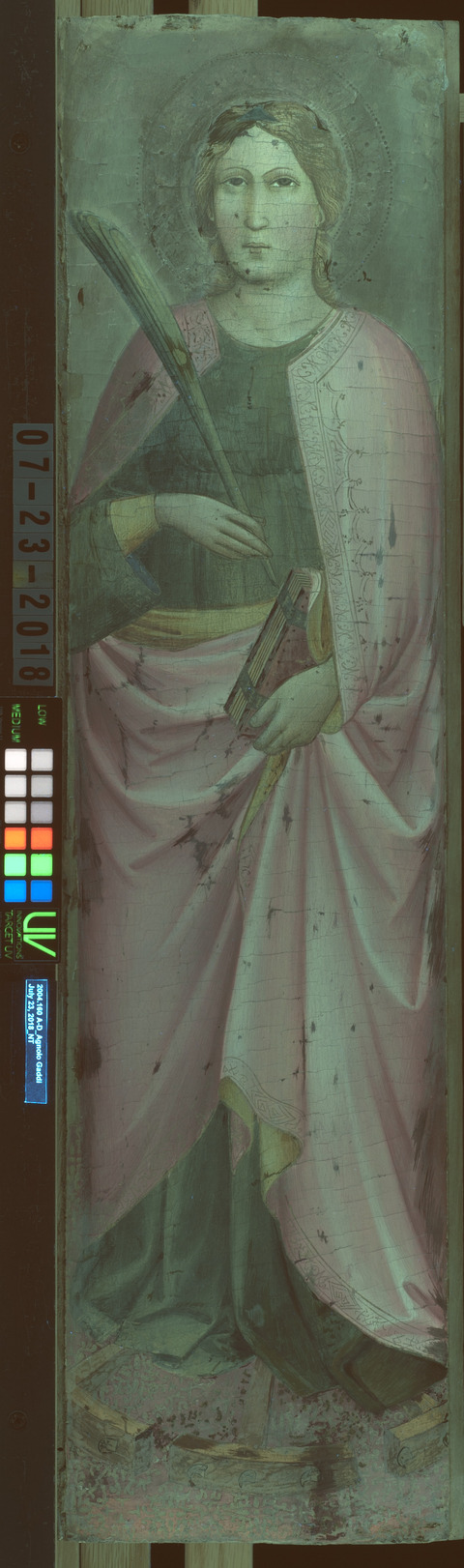

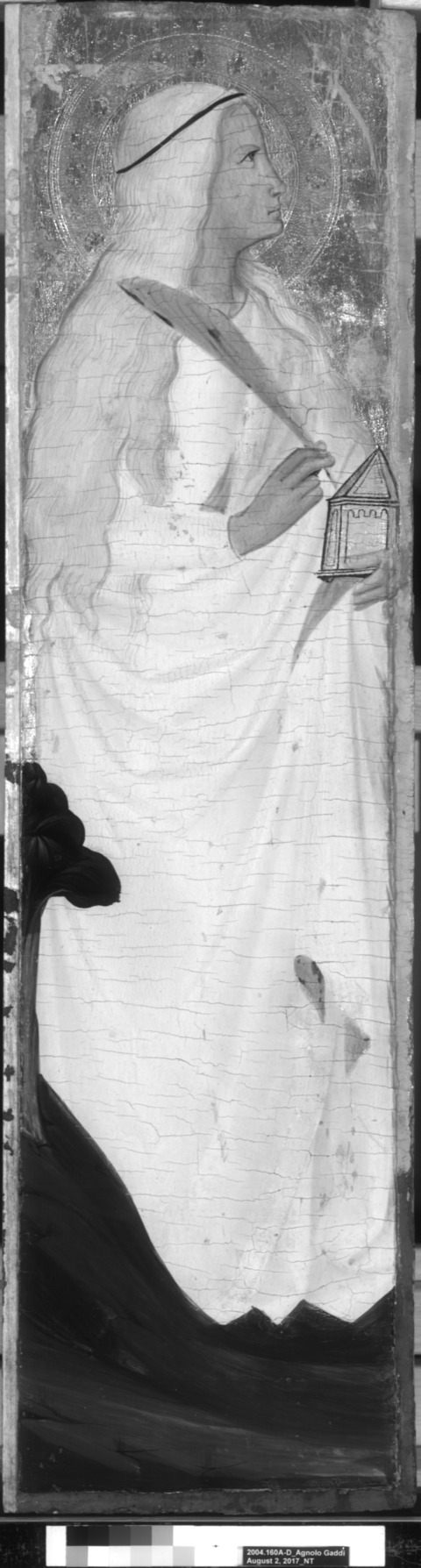

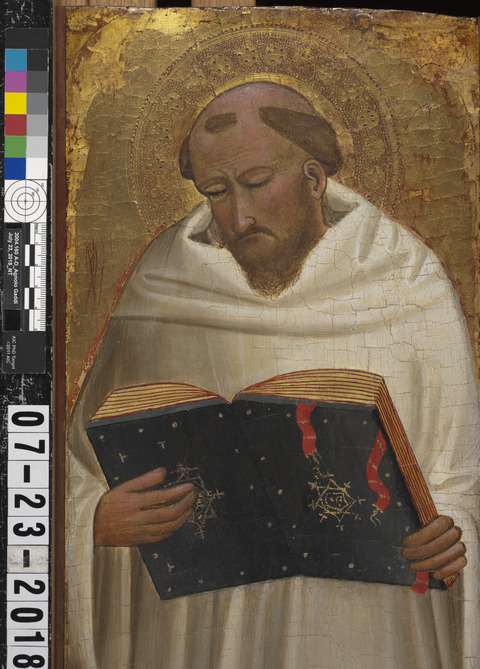

Accession number: 2004.160A-D

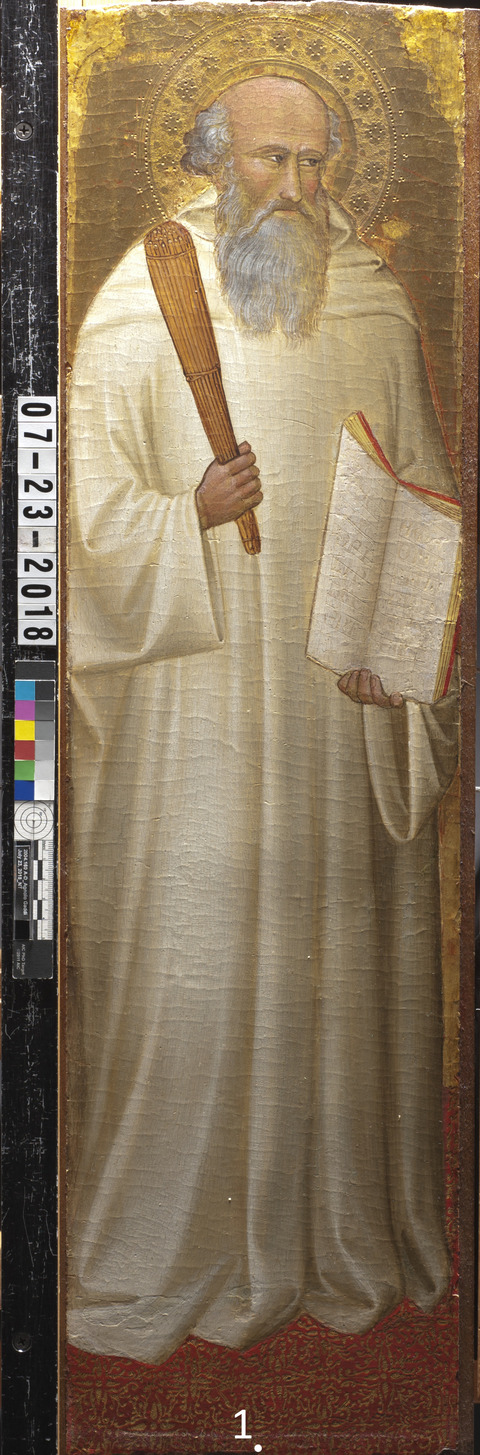

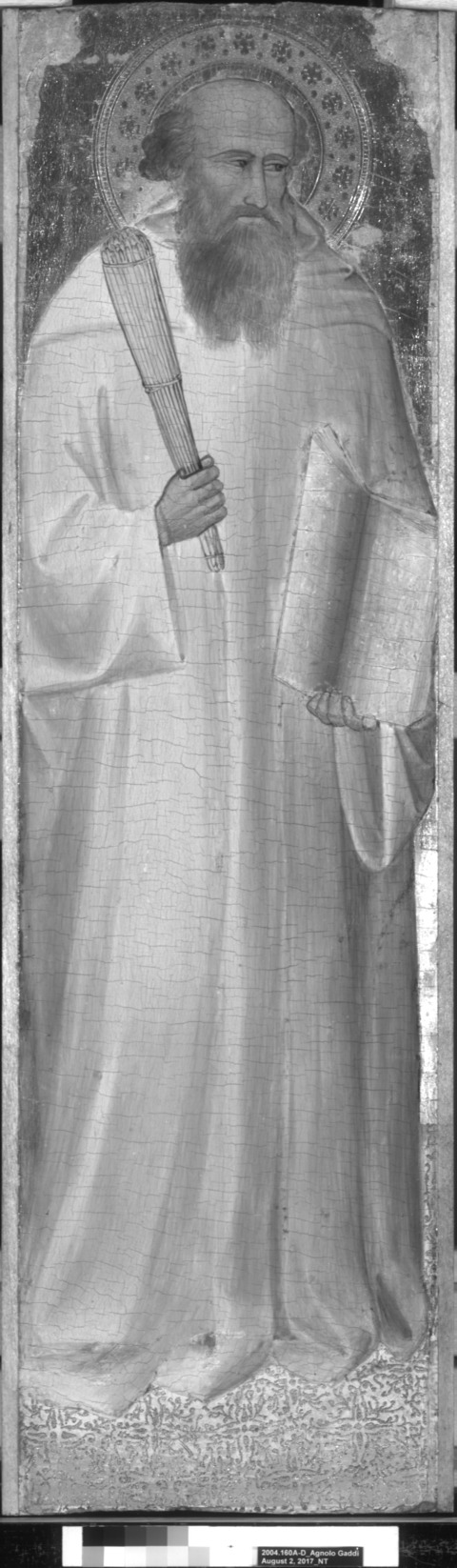

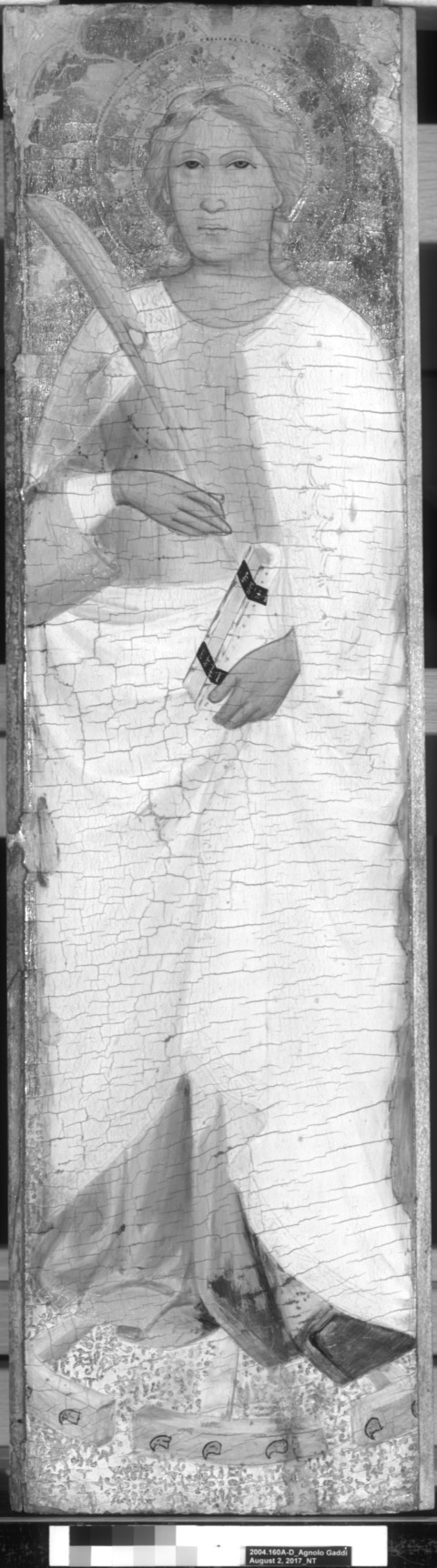

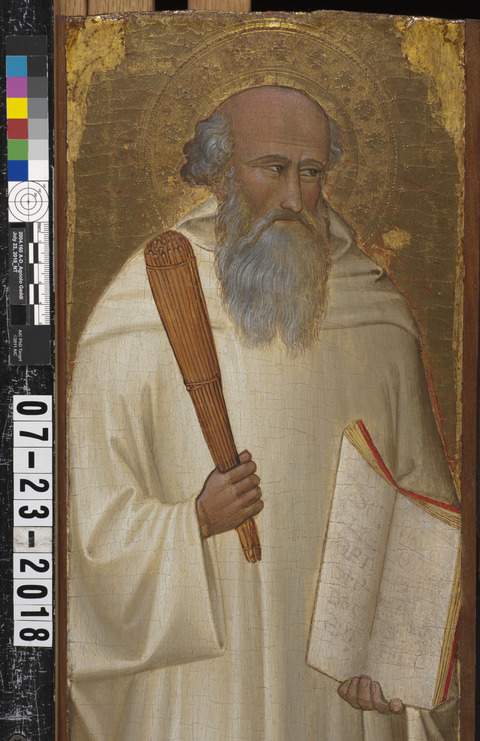

Artist: Agnolo Gaddi

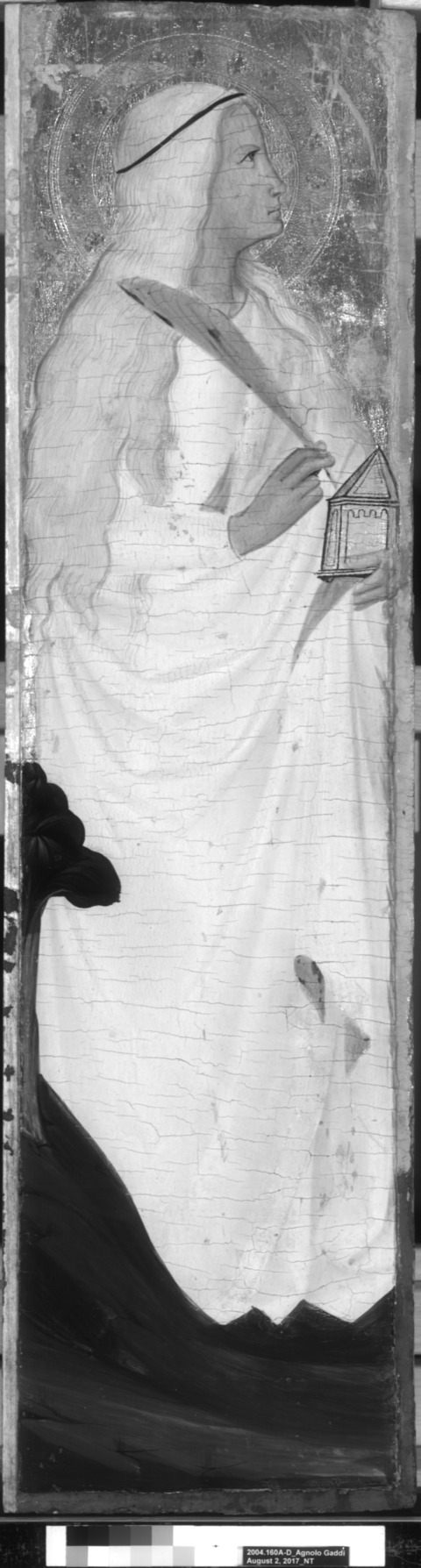

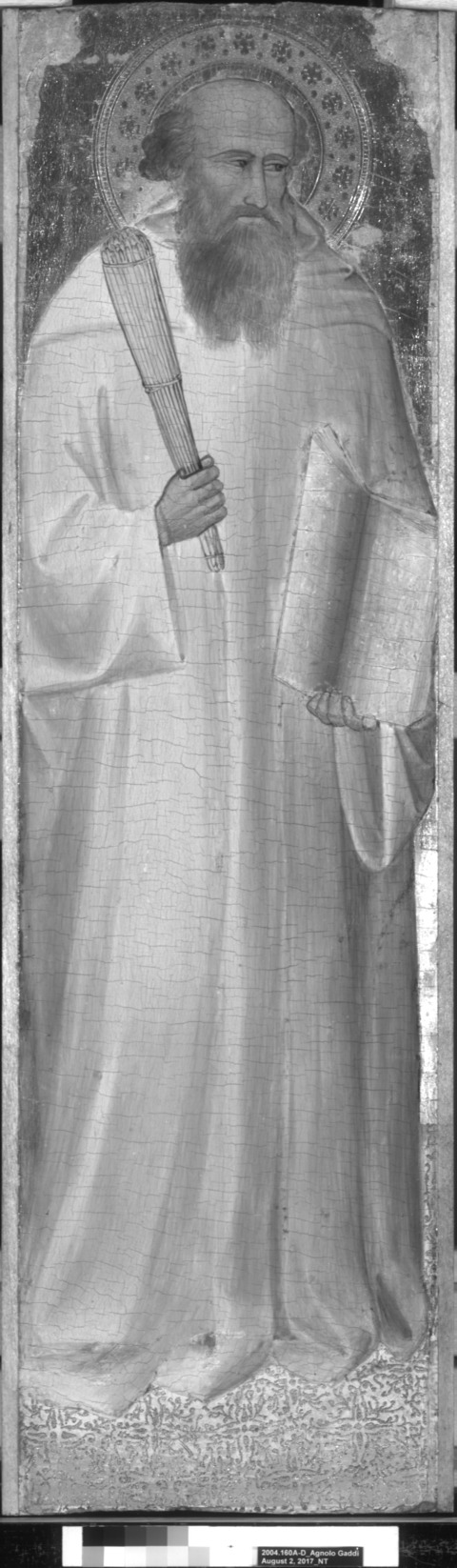

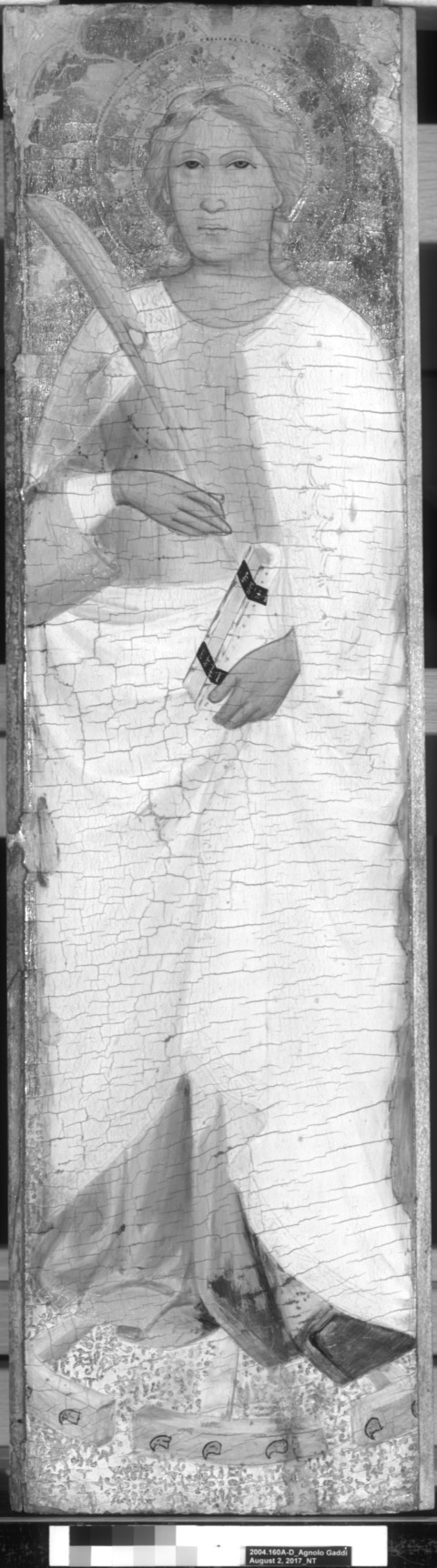

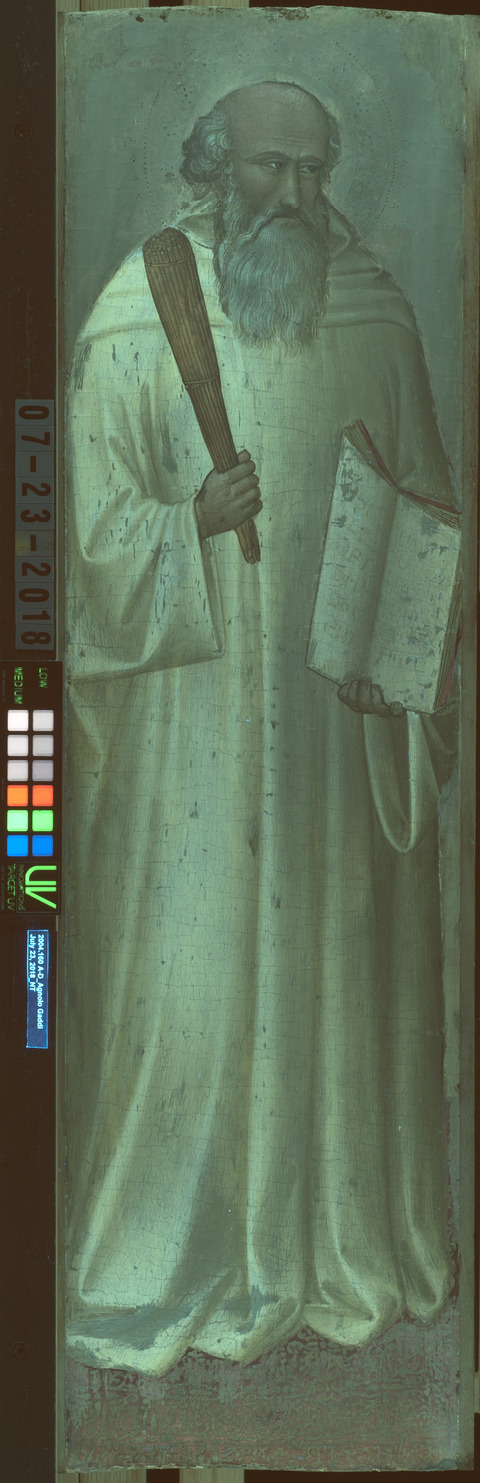

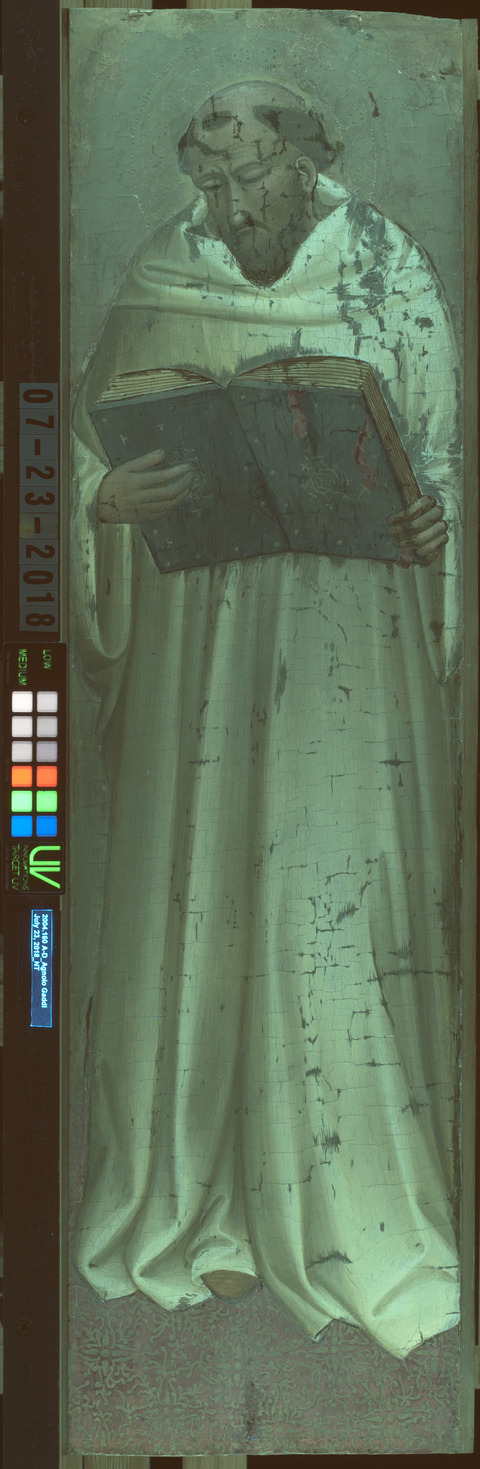

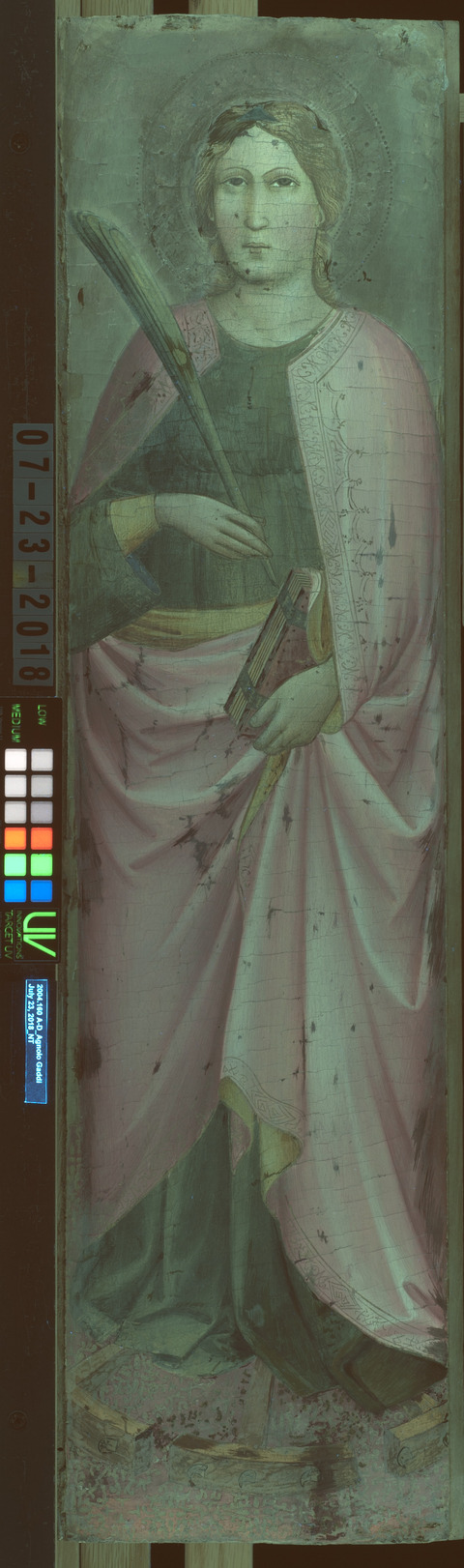

Title: St. Mary Magdalene, St. Benedict, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, and St. Catherine of Alexandria

Materials: Egg tempera (untested) and gilding on poplar panel

Date of creation: 1387–1388

Previous number/accession number: C10042

Dimensions:

| St. Mary Magdalene (A) | St. Catherine of Alexandria (B) | St. Benedict (C) | St. Bernard of Clairvaux (D) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current dimensions: | 73.5 × 19.5 cm | 73.7 × 20.1 cm | 73.9 × 21.6 cm | 73.6 × 21.6 cm |

| Original panel dimensions: | 73.5 × 19 cm | 73.7 × 19.4 cm | 73.9 × 20 cm | 73.6 × 20 cm |

Conservator/examiner: Roxane Sperber

Examination completed: December 2018

Distinguishing Marks

Front:

None

Back:

(see tech. fig. 76)

St. Mary Magdalene (A)

Item 1. Inscription, black crayon, top edge of cradle “111”

Item 2. Inscription, green pencil, right edge of cradle “6319 A FRAME”

Item 3. Inscription, pencil, top center-right vertical cradle member “*”

Item 4. Inscription, pencil, top second vertical cradle member from right “→”

St. Catherine of Alexandria (B)

Item 5. Inscription, black crayon, top edge of cradle “111”

Item 6. Inscription, green pencil, right edge of cradle “6319 B FRAME”

Item 7. Inscription, pencil/crayon top center-left vertical cradle member “- + 1”

Item 8. Inscription, pencil, top second vertical cradle member from left “+”

St. Benedict (C)

Item 9. Inscription, black crayon, top edge of cradle “111”

Item 10. Inscription, green pencil, right edge of cradle “6319 C FRAME”

St. Bernard of Clairvaux (D)

Item 11. Inscription, black crayon, top edge of cradle “111”

Item 12. Inscription, green pencil, right edge of cradle “6319 D FRAME”

Summary of Treatment History

The panels have been significantly altered since their creation in the late fourteenth century. They likely belonged to a large altarpiece, probably as pilaster panels, but the altarpiece was later dismantled and sold as pieces. The panels have been removed from their engaged frames and trimmed. The panels endured significant woodworm damage that may have prompted them to be thinned and cradled. Thin wooden strips have been added to the sides of one or both edges. Aesthetically, the paintings have been altered as well. They have been cleaned (likely numerous times), regilded in some areas, varnished with a synthetic coating, and retouched.

A condition assessment from New York restorer Edward O. Korany, dated 15 March 1958, describes the panels as having “blistering and detachment of paint from ground, and of ground from support on all four paintings varying in severity.” The panel described as “St. Matthew” was the worst affected. Korany noted that this condition must have been ongoing as prior restoration to deal with the issue was observed. The condition assessment recommended consolidation, or, if not possible, a complete transfer. Cleaning, insofar as is possible, was also recommended.1 It appears that Korany was successful in his consolidation attempts since the panels remain on their original support.

Documentation suggests a series of condition assessments and treatments were carried out on the collection at about the time the works were moved from the Clowes residence to the IMA in 1971. A condition report by Paul Spheeris in October of that year, likely carried out before the paintings were relocated, noted several chips on the frame. He did not recommend treatment.2 A second condition assessment was carried out upon arrival of the paintings at the IMA. This assessment described the work as being in good condition, and no work was deemed necessary.3

Current Condition Summary

Despite an extensive history of past interventions, the panels are in generally good condition both structurally and aesthetically. The panels are structurally stable, and the varnish appears saturating and clear. There is significant retouching present on all four panels, but it is mostly well matched and restricted to localized damages to the paint layer.

Methods of Examination, Imaging, and Analysis

| Imaging | Surface analysis (no sample required): | Analysis (sample required): |

|---|---|---|

| Unaided eye | Dendrochronology | Microchemical analysis |

| Optical microscopy | Wood identification | Fiber ID |

| Incident light | Microchemical analysis | Cross-section sampling |

| Raking light | Thread count analysis | Dispersed pigment sample |

| Reflected/specular light | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) |

| Transmitted light | Macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (MA-XRF) | Raman microspectroscopy |

| Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UV) | ||

| Infrared reflectography (IRR) | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) | |

| Infrared transmittography (IRT) | Scanning electron microscope -energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) | |

| Infrared luminescence | Other: | |

| X-radiography |

Technical Examination

Description of Support

Analyzed Observed

Material (fabric, wood, metal, dendrochronology results, fiber ID information, etc.):

Each panel is composed of a single, tangentially sawn poplar/willow plank with vertically oriented grain.4

Characteristics of Construction / Fabrication (cusping, beveled edges of panels, seams, joins, battens):

The question of exactly how these panels fit into the larger altarpiece is difficult to determine with certainty from the remaining artifacts. It has been suggested that the panels functioned as pilasters on either side of a large altarpiece.5 The panels would have likely been placed in engaged frames, and the gesso from the panels would have extended over the engaged frame. When engaged frames are removed a barb is often visible where the gesso was built up to go over the wood of the frame. None of the panels shows clear evidence of barbs along the edges, suggesting they were trimmed slightly smaller than their original dimensions, perhaps to “clean up” the edges.

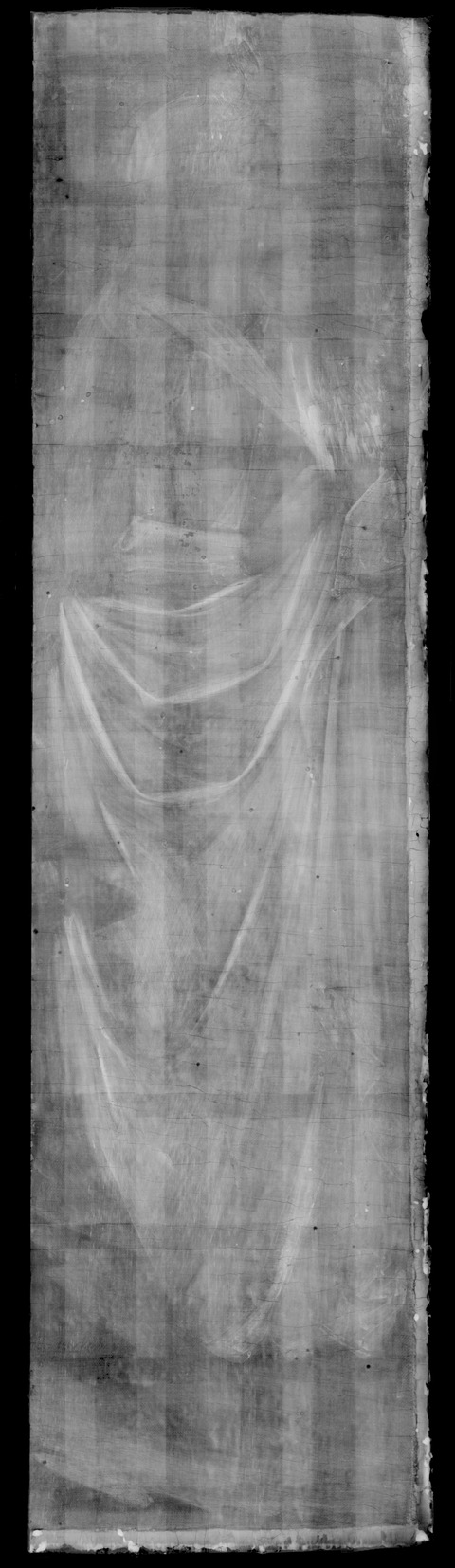

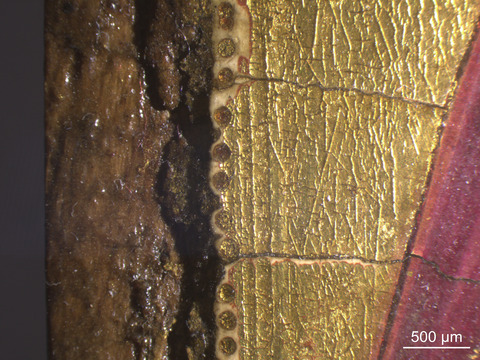

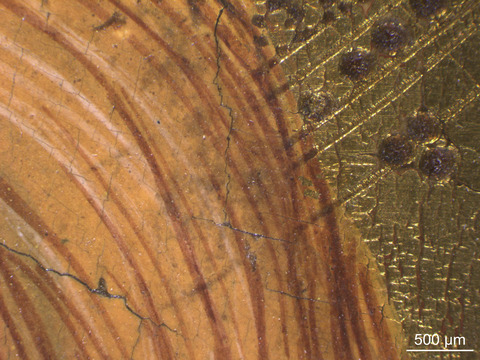

There are a series of punchwork dots visible along the left edge of the St. Catherine of Alexandria panel (tech. fig. 5) as well as remnants along the left and right edges of the St. Bernard panel. Curved arches of similar punchwork are also visible on the top portion of the St. Bernard, although these areas have been covered with restoration gilding. These remains may be evidence of an original punched border that marked where the engaged frame met the picture plane. If so, the arched dots suggest the panels were not originally squared but pointed at the top (as was typical of Gothic altarpieces).

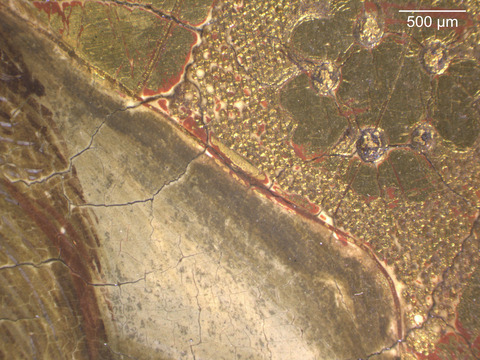

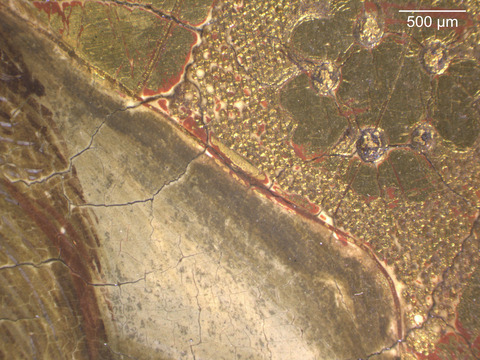

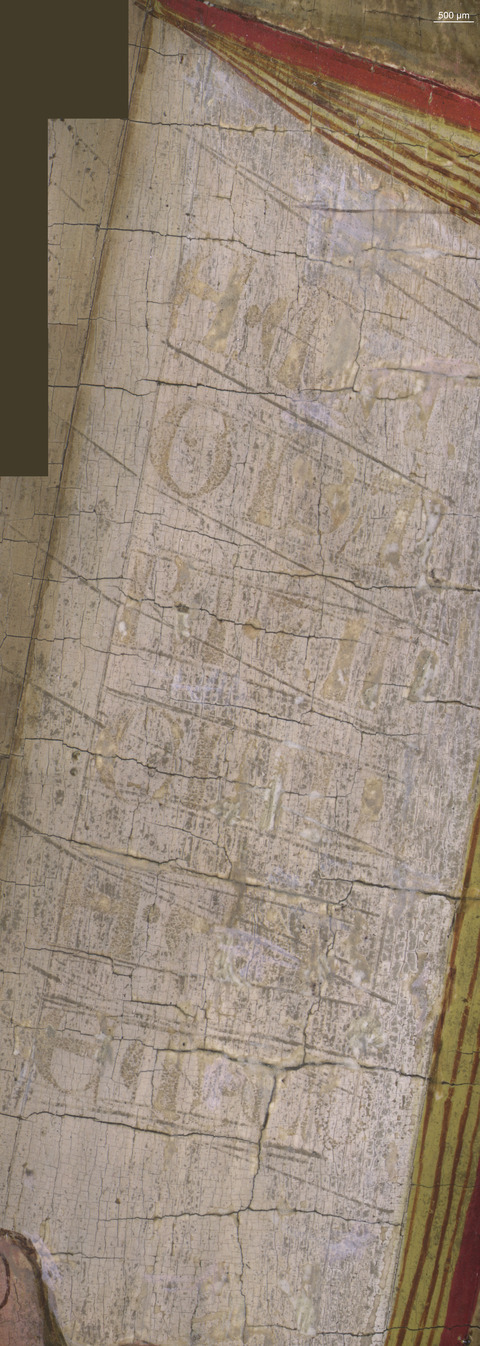

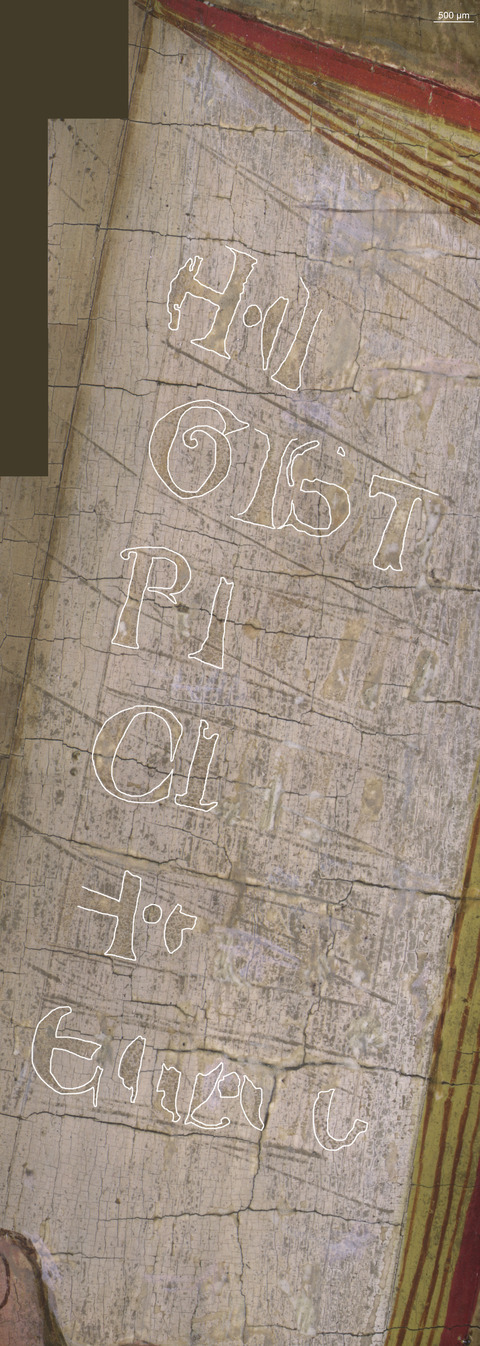

Incision lines along the top edge of the St. Benedict (tech. fig. 6) and St. Bernard of Clairvaux panels have been inscribed into the original gilding. They appear to have been made to guide the trimming of the panel.

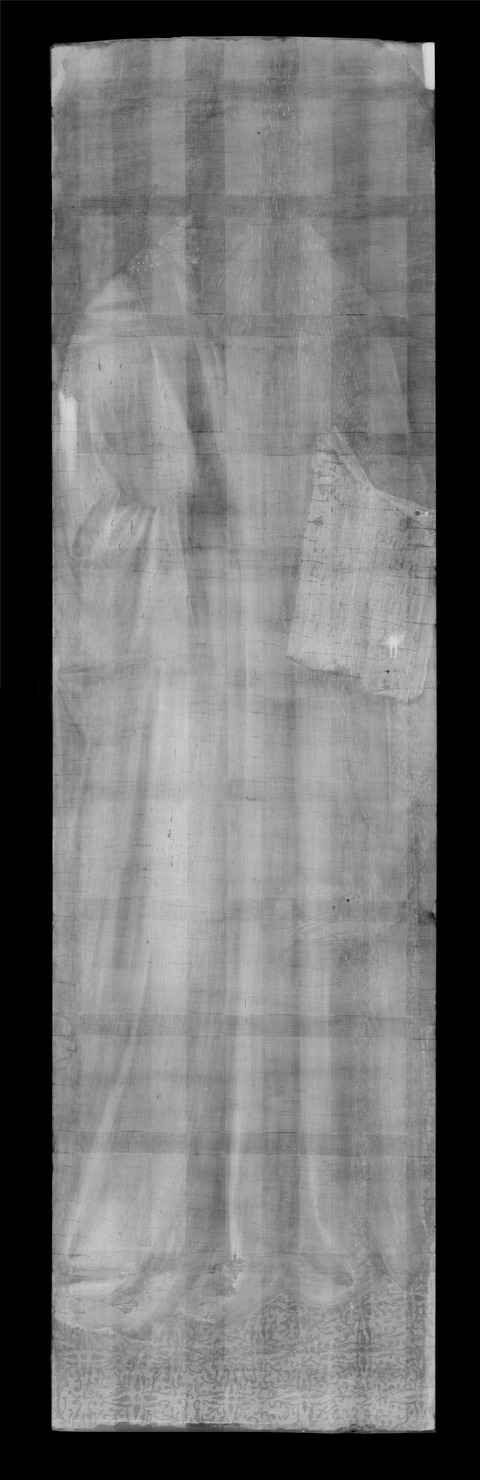

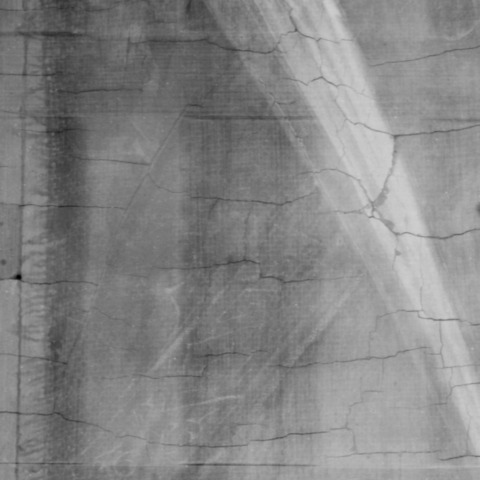

St. Mary Magdalene (A)

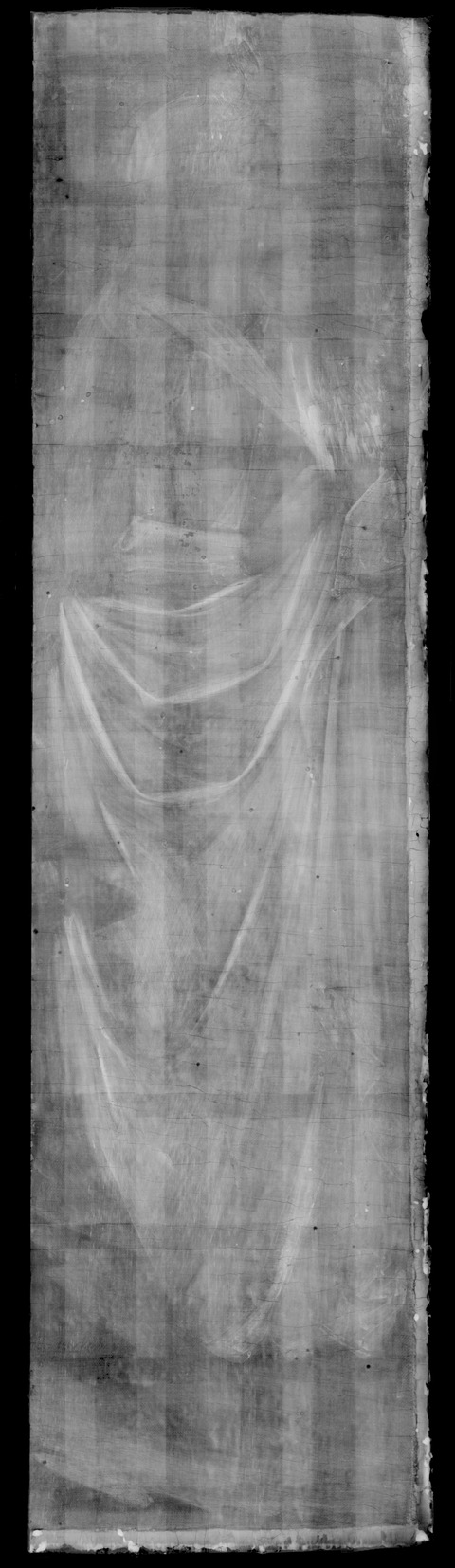

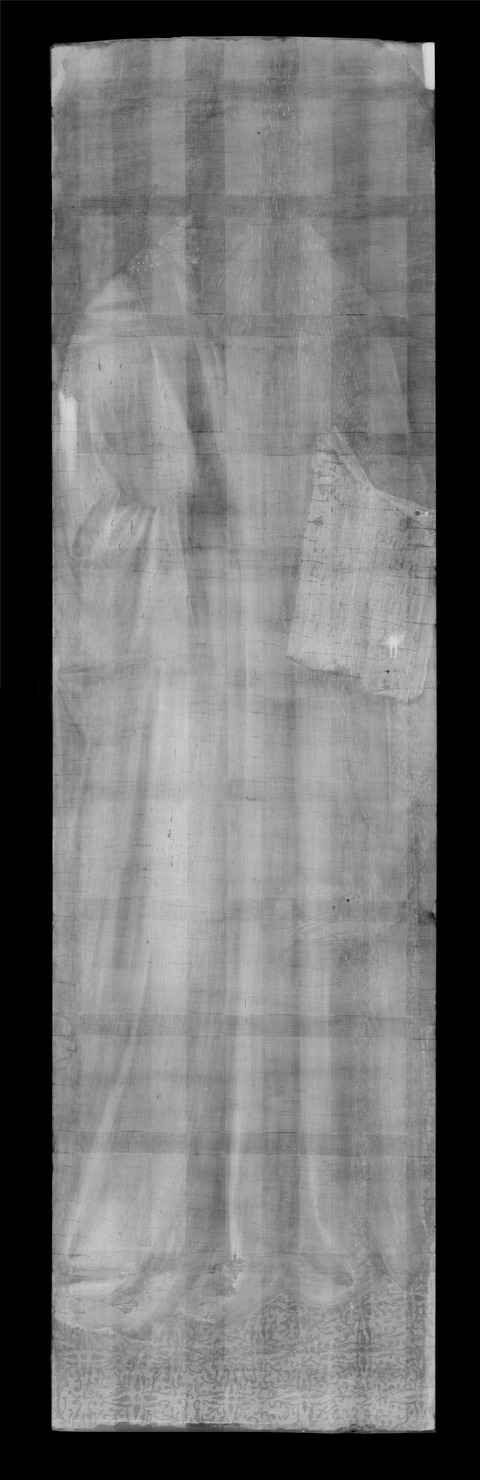

A wooden strip has been inserted on the left side of the panel. The original support extends to the right edge of the panel. However, a painted border of nonoriginal fill has been added along the right edge and the bottom of the original support. This fill is more X-ray dense than the original ground and can be differentiated in the X-radiograph. As was typical of the period, fabric has been applied to the entire picture plane and can also be observed in the X-radiograph (tech. fig. 1). The canvas does not extend under the nonoriginal fill, suggesting that the painted image did not originally extend over these areas.

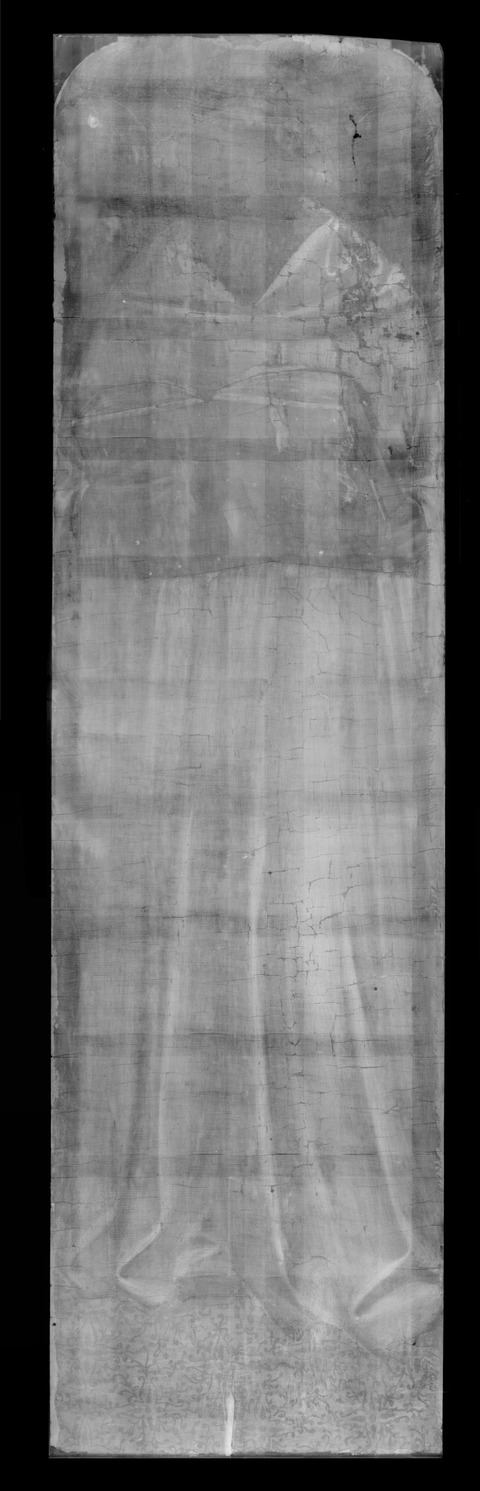

St. Catherine of Alexandria (B)

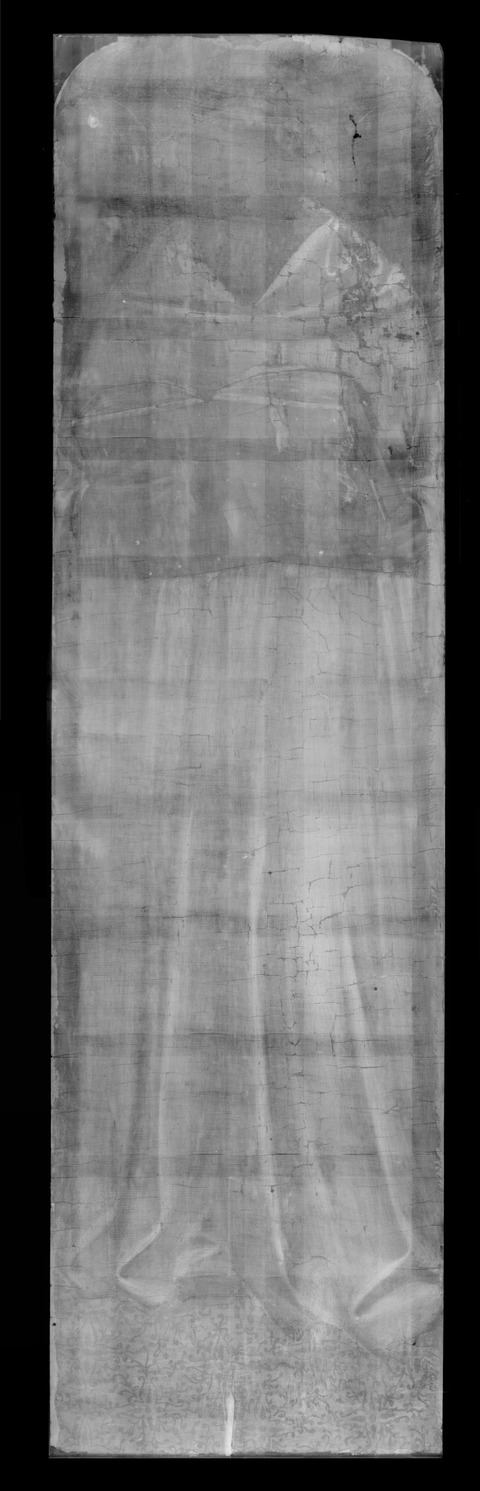

A wooden strip has been inserted on the right side of the panel. The original support extends to the left edge of the panel. The original support along the left edge has been mostly left exposed, in contrast to the St. Mary Magdalene panel where the strip of original support was completely filled and retouched. However, the upper-left edge of the panel and upper-left corner have been filled in order to square the panel (tech. fig. 2).

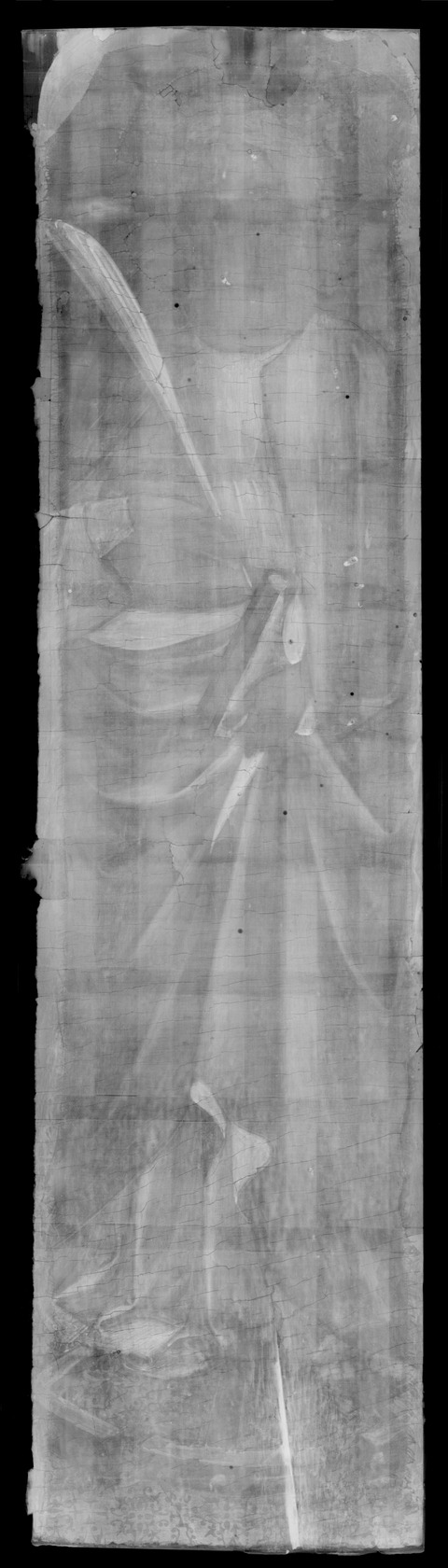

St. Benedict (C)

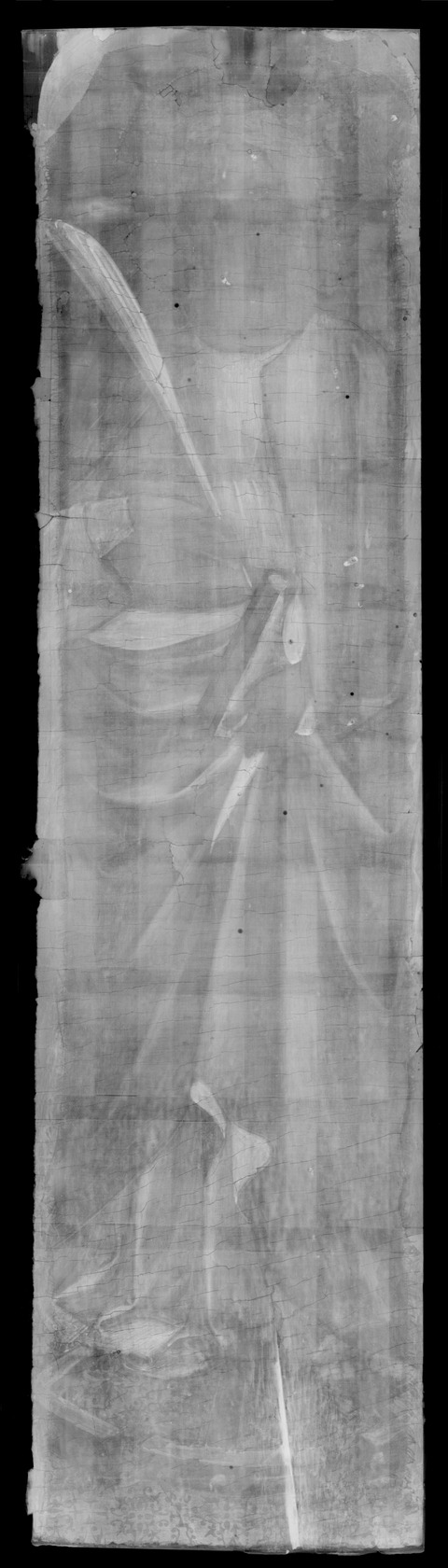

Wooden strips have been inserted on the left and right edges of the panel (tech. fig. 3).

St. Bernard of Clairvaux (D)

Wooden strips have been inserted on the left and right edges of the panel (tech. fig. 4).

Thickness (for panels or boards):

| Original panel (thinned) | Support with cradle | |

|---|---|---|

| St. Mary Magdalene (A) | 7 mm | 28 mm |

| St. Catherine of Alexandria (B) | 7 mm | 32 mm |

| St. Benedict (C) | 7 mm | 30 mm |

| St. Bernard of Clairvaux (D) | 7 mm | 30 mm |

Table 1: Thickness of the original support and thickness of the support with the cradle

Production/Dealer’s Marks:

None

Auxiliary Support:

Original Not original Not able to discern None

The panels have cradles that are identical in construction. Each cradle is composed of six fixed vertically oriented members and twelve horizontally oriented members that are movable. The spacing of the vertical members is adjusted to fit the width of each panel. Strips of wood have been added to the right and left sides of the St. Benedict and St. Bernard panels. Similar edge strips have been added to the left edge of the St. Mary Magdalene panel and the right edge of the St. Catherine panel. These appear to have been part of the construction of the cradles.

Attachment to Auxiliary Support:

Edge strips, where present, are glued in place. The vertical members of the cradle have been glued to the thinned back of the panels and edge strips. Remnants of glue are visible in some areas.

Condition of Support

The supports of all four panels have been significantly altered—cut from the original altarpiece, trimmed, thinned, and cradled. Evidence of past woodworm damage is visible on the backs of all four panels. However, in their current configuration, the panel supports are in stable condition.

Description of Ground

Analyzed Observed

Materials/Binding Medium:

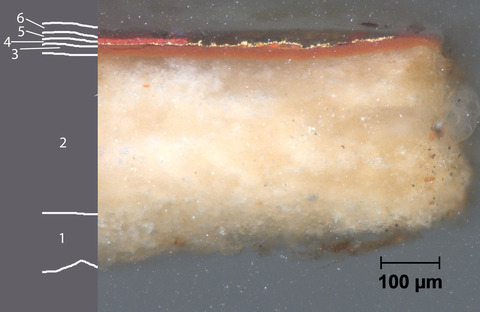

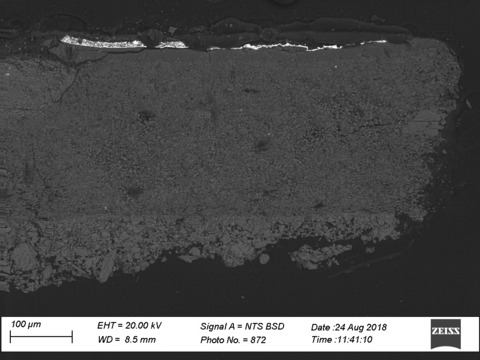

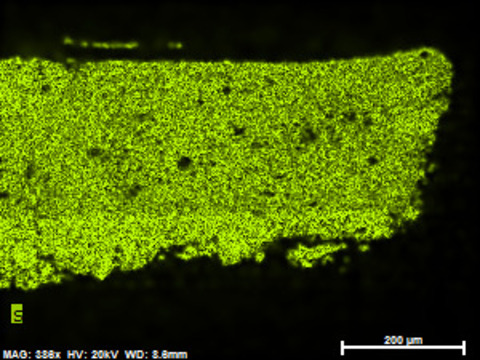

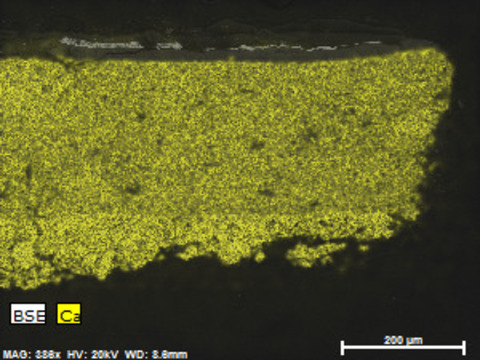

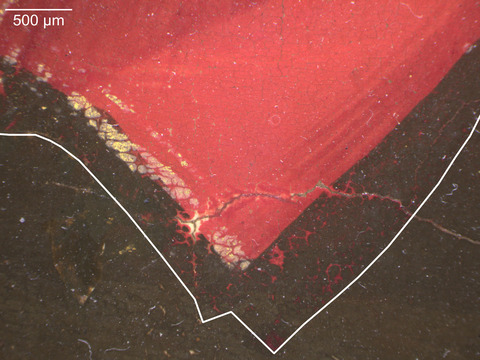

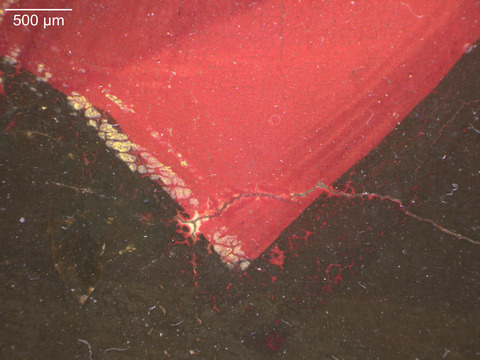

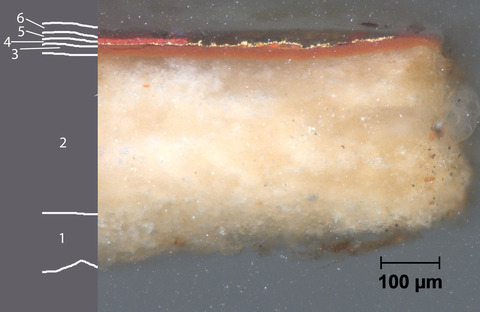

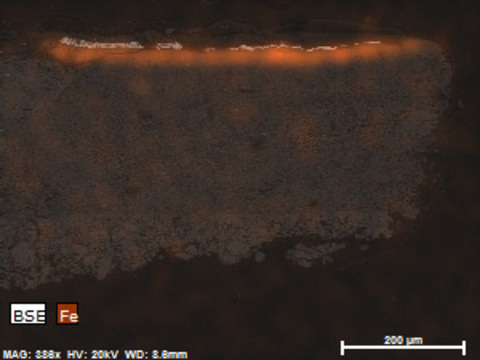

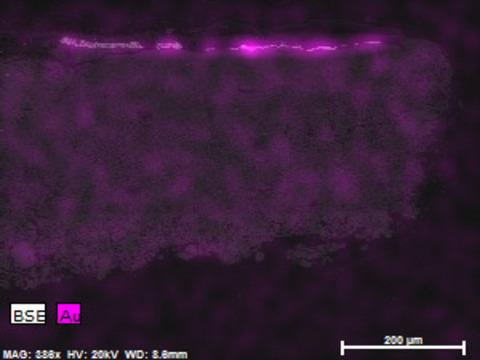

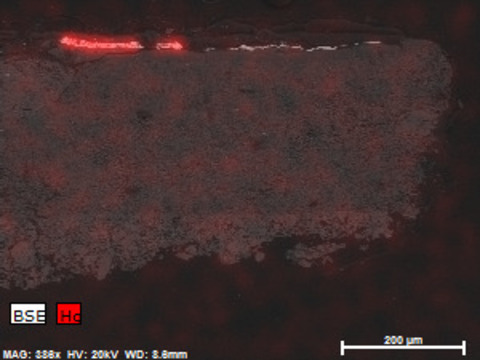

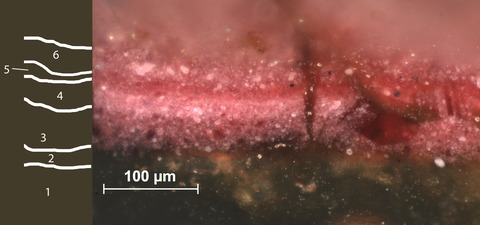

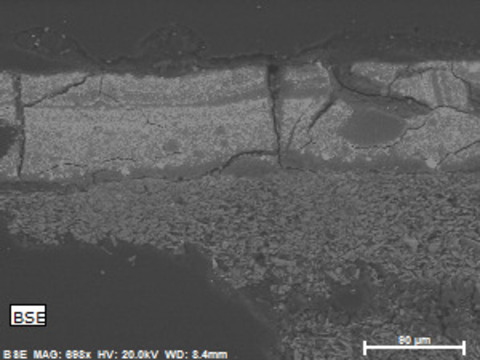

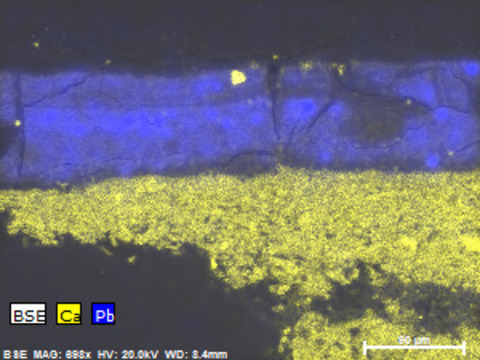

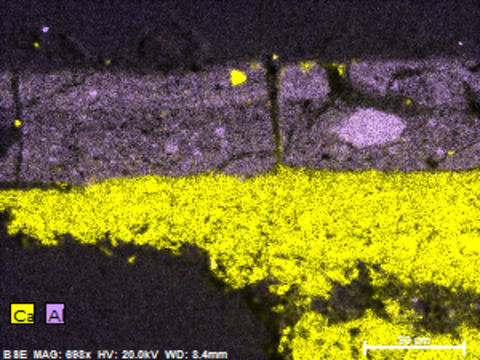

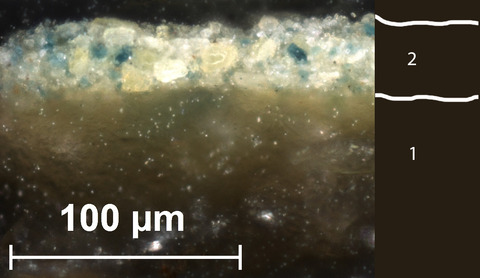

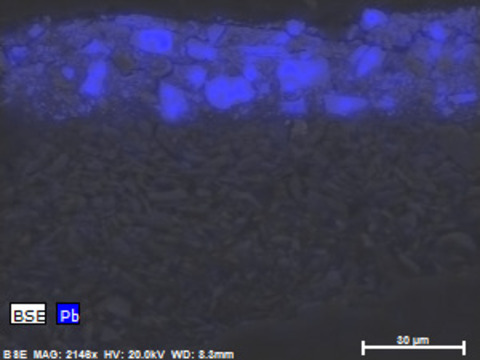

A cross-section sample was taken from the sgraffito at the bottom of the red decorative cloth where St. Benedict stands (tech. fig. 7). This sample shows the layer structure of the ground (tech. fig. 8). The panel is prepared with a layer of canvas followed by two layers of ground (tech. fig. 9). The ground is composed of calcium sulfate (gesso) (tech. figs. 10, 11), as would be expected for an Italian panel of this period.6

Color:

White

Application:

Before the application of the ground, a layer of canvas was adhered to the wood, likely using glue size. The frayed canvas at the edge of the panel, visible in X-radiography (tech. fig. 12), suggests that the canvas did not extend over the engaged frames but was cut to fit the painted surface. The presence of frayed edges of canvas may give a clue to the original structure of the altarpiece. The uneven and frayed canvas suggests the original edge of a painted surface. Where the canvas extends off the edge of the panel, it is likely that the painting was either trimmed or was originally part of a larger panel that the canvas covered.

The X-radiograph shows that the right edge of St. Mary Magdalene has frayed canvas suggesting the current edge is the original edge of the painted surface (tech. fig. 13). The original support extends beyond the original ground and paint layer suggesting the original engaged frame was attached to that area. Both edges of the St. Catherine panel have uneven and frayed canvas, suggesting that this panel had an engaged frame on either side (tech. fig. 14). This evidence is also supported by the punchwork along the edge (tech. fig. 5), which may be evidence of a decorative border along the engaged frame.7 The right edge of the St. Bernard panel has a visibly frayed edge (tech. fig. 15), but the canvas appears to have extended beyond the left edge of the current dimensions. This is also true for both the right and left edges of the St. Benedict panel.

The ground was applied over the canvas in two layers following the technique described by Cennino Cennini.8 A thin layer of gesso grosso was applied first to even the panel. A thicker layer of finely ground gesso sottile was applied over the gesso grosso to create a smooth surface for painting. These distinct layers can be observed in the backscattered-electron image (BSE) (tech. fig. 9).

Thickness:

The gesso layer on the cross-section sample is approximately 300 µm thick. The gesso grosso layer is approximately 100 µm, although it may vary depending on the area of the panels. The gesso sottile layer on the cross-section sample is approximately 200 µm.

Sizing:

The panel was likely sized when the canvas was applied. There may be a second layer of sizing over the gesso, but this cannot be conclusively determined from the cross-section sample.

Character and Appearance (Does texture of support remain detectable / prominent?):

The surface is relatively smooth and even, and impasto is not visible in the paint.

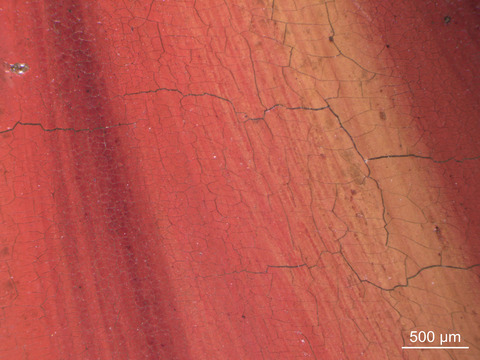

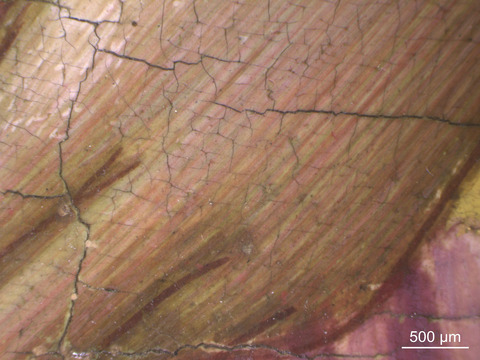

Condition of Ground

The ground is in generally good condition. There is a prominent craquelure pattern on all four panels that extends through the ground and paint layer. There are localized losses on all of the panels, including a large area of fill on the halo of St. Catherine. The fill extensions can be differentiated from the original ground in the X-radiograph. After the altarpiece was taken apart, the panels, which were likely originally scalloped or pointed, were squared at the top. Restoration gilding is present on all four upper corners of the panels. However, this restoration does not appear to correspond to modern fills in all cases. It is possible that when engaged frames were removed the ground was disrupted on some panels but not in others. From the X-radiograph, the original ground appears to be intact in the upper corners of the St. Mary Magdalene panel. The ground was extended along the bottom and right edges of the St. Mary Magdalene panel. Fills have been added to the upper corners of the St. Bernard, St. Catherine, and St. Benedict panels in order to square the picture plane. The restoration gilding extends beyond where the fills have been added.

Description of Composition Planning

Methods of Analysis:

Surface observation (unaided or with magnification)

Infrared reflectography (IRR)

X-radiography9

Analysis Parameters:

| X-radiography equipment | GE Inspection Technologies Type: ERESCO 200MFR 3.1, Tube S/N: MIR 201E 58-2812, EN 12543: 1.0mm, Filter: 0.8mm Be + 2mm Al |

|---|---|

| KV: | 26 |

| mA: | 3.0 |

| Exposure time (s) | 120 |

| Distance from X-ray tube: | 36” |

| IRR equipment and wavelength | Opus Instruments Osiris A1 infrared camera with InGaAs array detector operating at a wavelength of 0.9-1.7µm. |

Medium/Technique:

No underdrawing can be observed in the infrared reflectograms of the panels or with the naked eye (tech. figs. 16–19). The Coronation of the Virgin by Agnolo Gaddi in the National Gallery London also does not have underdrawing that is visible in infrared, but a liquid medium, perhaps iron gall ink, was observed with the naked eye.10 The figures on the Indianapolis panels do, however, appear to have been carefully planned. Inscision lines outlining the compositions are present on every panel (see Description of Paint).

Pentimenti:

There are very few pentimenti on the panels, suggesting the compositions were carefully determined before the painting stage. A subtle change was made to the bottom of St. Mary Magdalene’s robe during the painting stage when the shape was adjusted slightly by extending the ground plane (tech. fig. 20).

Description of Paint

Analyzed Observed

Application and Technique:

Cennino Cennini, the author of Il libro dell’arte, a treatise on early Italian painting technique, was a longtime apprentice and collaborator of Agnolo Gaddi.11 Unsurprisingly, the painting technique on the panels closely follows that described by Cennini.

Incisions:

After the compositions of the panels were established, the contours delineating the areas that were to be painted from those that were to be water gilded were incised into the ground. Although some of the incision lines are now obscured by paint, incisions can be observed on all four panels. They are particularly prominent around the heads and hair of the saints (tech. fig. 21), along the edges of the robes (tech. figs. 22, 23), around St. Bernard’s feet (tech. fig. 24), and outlining St. Catherine’s attributes, including the martyr’s palm and wheel. While the incision lines are extensive, they are not particularly refined or specific. For instance, the profile of St. Mary Magdalene was roughly delineated with a single straight insicion line from her nose to her chin (tech. fig. 25). The details of her profile were later refined during the painting stage.

Water Gilding:

Large portions of all four panels have been water gilded, including the background of all four panels and the ground plane of St. Bernard, St. Benedict, and St. Catherine. The ground plane of St. Mary Magdalene was not gilded since it was painted to appear as a rocky landscape rather than a decorative fabric.

A thick layer of iron-rich red bole was applied to the areas that were to be gilded (tech. figs. 30, 31). The bole was then wetted, and gold leaf was applied. XRF analysis of the original gilding suggests it is a pure gold leaf (see XRF Analysis). The water gilding was burnished to create a glittering surface. As is recommended by Cennini, the halos and punchwork appear to have been carried out before the painting stage.12 A detail from the St. Mary Magdalene panel (tech. fig. 26) shows where the paint of the saint’s hair covers the incision lines used to create the outlines of the halo.

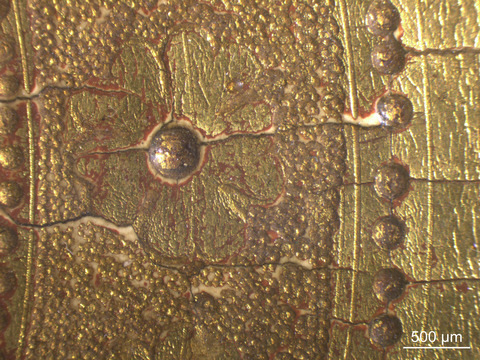

Punchwork:

The punchwork is relatively simple in comparison to other works attributed to Agnolo Gaddi.13 Each saint has a slightly different halo pattern created using different combinations of a few simple punches. There is a five-lobed floret punch that is used on all four panels (tech. figs. 27, 28). This punch is identified by Erling Skaug as punch 441 and is described by Skaug as a “unique” punch as it is only used on one other work by Gaddi.14 A small round punch is used in the halo on St. Benedict but does not appear to have been used on the other saints. Freehand dots, using both a large and small punch, are applied throughout to embellish the florets and create designs around the halos.

The halo design on St. Catherine differs from the other three panels in that there is a single large dot punched in the center of the five-lobed florets (tech. fig. 27). On the other three panels, the florets are embellished with five dots applied between each petal of the floret (tech. fig. 28). Clusters of three dots are applied around the outside of the St. Benedict and St. Mary Magdalene halos. These clusters are applied freehand as they vary in spacing and design (tech. fig. 29). A stippling technique was used behind the florets in the halos to create a textured surface that glitters when it catches the light.

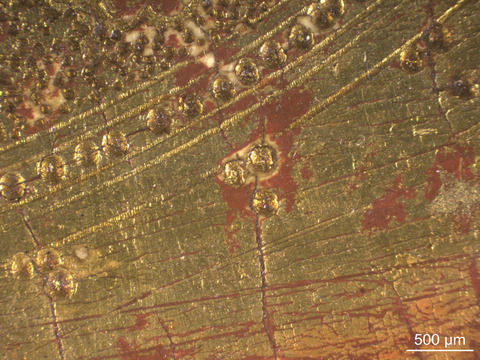

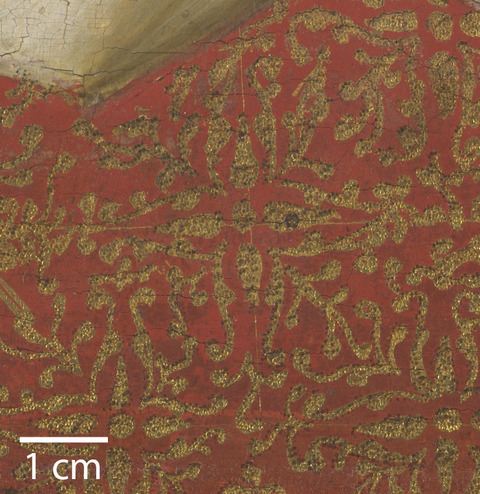

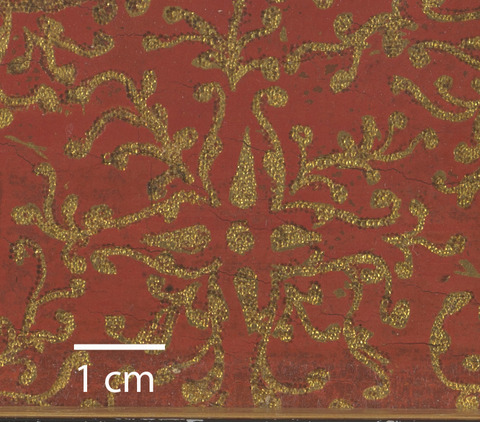

Sgraffito:

A cross-section sample from the lower edges of St. Benedict illustrates the sgraffito pattern on the panels (tech. figs. 30–33). Over the gilded surface a layer of vermilion paint was applied (tech. fig. 33). If the artist followed the technique described by Cennini, the brocade pattern was then transferred using a pouncing technique and free pigment.15

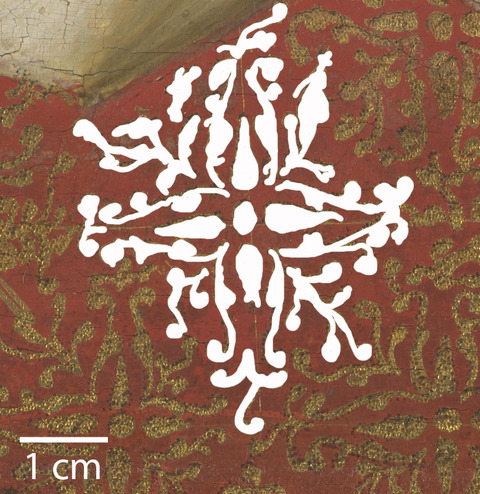

A floral pattern does repeat on all three panels (tech. figs. 34, 35), although its organic shape suggests it may have been transferred by eye rather than using a stencil (tech. fig. 36). The central portion of the decorative pattern can be found to consistently repeat, although even this area is not identical when overlaid from one panel to another. Linear incisions on the decorative brocade of the St. Benedict panel (tech. fig. 34) may have been used to guide the registration of the repeated portions of the pattern. The pattern was subsequently scratched into the paint to reveal the gilding.16 Stippled punchwork was then applied to the gilded areas.

The Application of Paint:

The paint application on the four panels follows generally the same technique and closely follows the method described by Cennini. The compositions were carefully established before the painting phase, and there is little overlap between the passages of color, making it difficult to determine the exact order of paint application. This may point to a workshop production where one artist was responsible for drapery while another painted the hands and face.

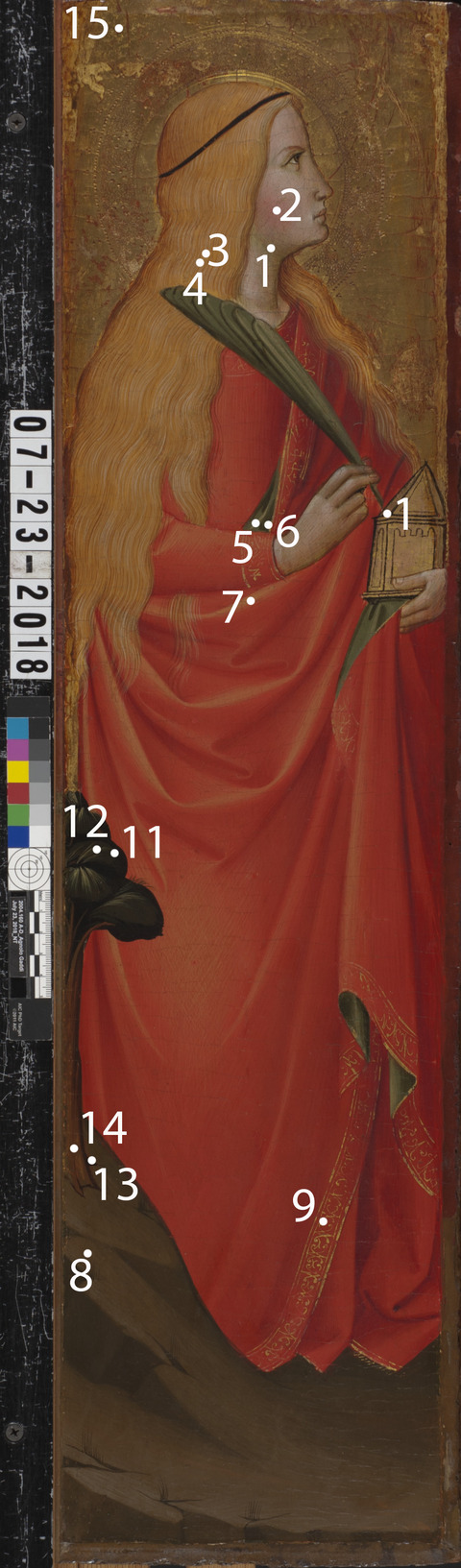

St. Mary Magdalene (A)

From what overlaps are present, it appears that the robes and attributes of the St. Mary Magdalene were painted before the hands and face (tech. fig. 37), as is recommended by Cennini. The paint was applied following the incision lines that established the composition. The red drapery was created by painting the entire area with the red midtone before applying the red glaze to create the shadows and thin strokes of yellow paint to create the highlights (tech. fig. 38). This differs from the technique that is recommended by Cennini where progressive amounts of white are added to a pigment to create the midtone and highlights.17 The green lining of the robe and the martyr’s palm attribute were painted after the red robe. In the green areas, the artist followed Cennini’s instructions more closely, laying in the dark green first and blending into the midtone and highlight, which appear to have been mixed by adding white, or perhaps yellow, to the green glaze.

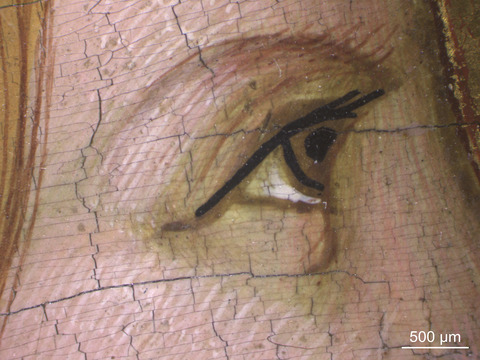

St. Mary Magdalene’s face was painted using a traditional green verdaccio layer to create the shadows. Over the verdaccio, strokes of pink were applied in small brushstrokes. White highlights were applied on the nose, corner of the mouth, and cheek bones. The rosy cheeks were applied over the midtone skin color and, as described by Cennini, “more toward the ear than toward the nose, because they help to give relief to the face."18 The facial features and hands were outlined with a light brown paint that was also used to paint the delicate hairs on the eyebrow (tech. fig. 39). The eye was articulated with a few quick strokes of dark black paint. Black outlining was also used to define the contours of the gilded attribute in the figure’s hand.19

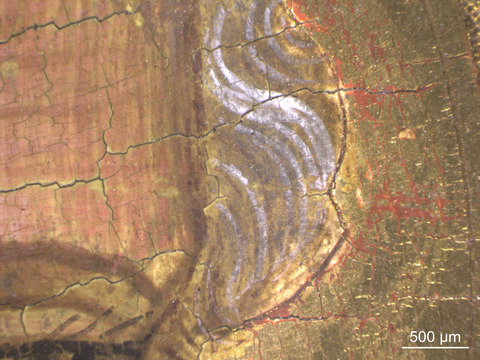

Mary Magdalene’s hair was blocked in using a bright orange midtone at the same time as the drapery was painted. After the composition was complete, delicate strokes of undulating white, brown, and orange paint were added to give the appearance of individual strands of hair (tech. fig. 40). These strokes extend onto the figure’s face and over the red robe to create the appearance of long locks of hair gently falling over her arm.

The ground plane was painted after the robes were completed using a midtone and shadow to create rocky forms. Strokes of dark paint were added over the rocks to create cracks in the rocks and other linear detailing.

St. Catherine of Alexandria (B)

The St. Catherine panel has the most colorful panel with swatches of pink, green, yellow, and blue (tech. fig. 41, see XRF analysis tech. fig. 70, table 5). The paint was applied following the incision lines that established the composition. As with the St. Mary Magdalene panel, the drapery and attributes were painted first, leaving reserves for the skin paint. The pink drapery was painted following the technique described by Cennini with a red lake pigment (untested) for the shadows and mixed with progressively more lead white for the midtones and highlights (see tech. fig. 42).20 Unlike the red robe of Mary Magdalene, the midtone was not applied to the entire cloak. Rather, three tones of pink were applied in distinct areas and blended to create transitions in the folds.

A cross-section sample (tech. fig. 54) from one of these transitions shows a rather more complex buildup of paint layers than might be expected from Cennini’s description. On top of the ground, a dark red lake glaze, containing no lead white, was applied to create the shadow in the folds. No less than four more layers of pink paint followed, each containing varying quantities of lead white. This area depicts the blending of the midtone into the shadow where strokes of lighter, opaque pink paint were applied over the deepest red glaze to create the appearance of a smooth transition from shadow to highlight.

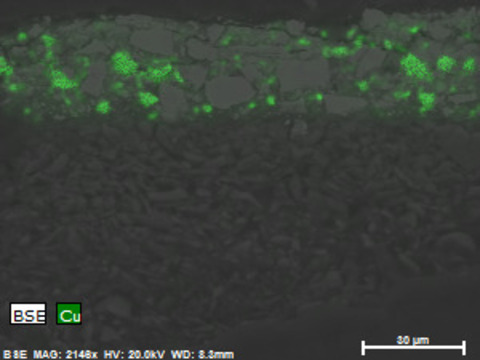

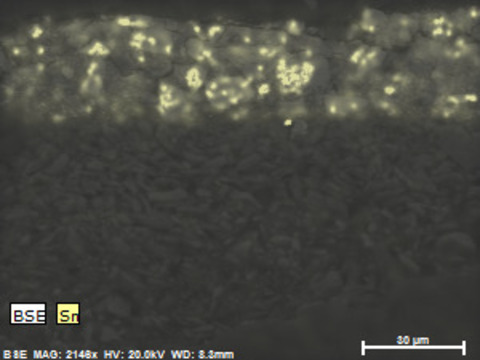

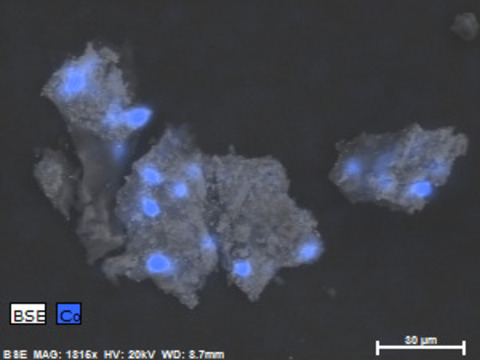

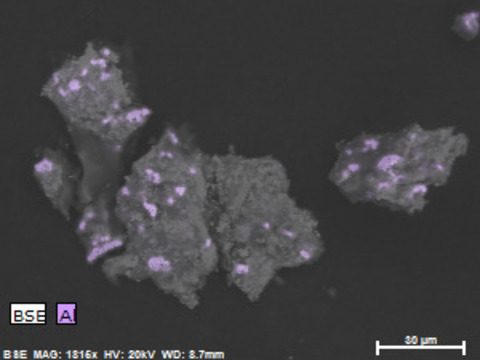

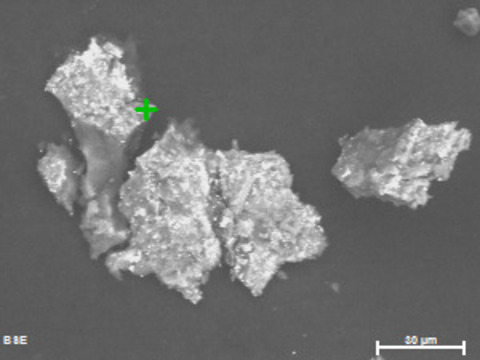

After the pink drapery was finished, the passages of the green dress were painted using a combination of lead-tin yellow and azurite (see green). It is unclear whether lead white was added to the brightest highlights in the dress. Elemental mapping (using EDS) of a cross section from a midtone area of green showed the distribution of tin and lead to overlap (see tech. figs. 60, 61). This suggests the presence of lead can be attributed to the lead-tin yellow rather than the addition of lead white. The yellow lining of the robe was painted next followed by the blue inner sleeve of the hand with the martyr’s palm. The red book appears to have been painted early in the painting process following incised lines that were used to create the illusion of perspective.

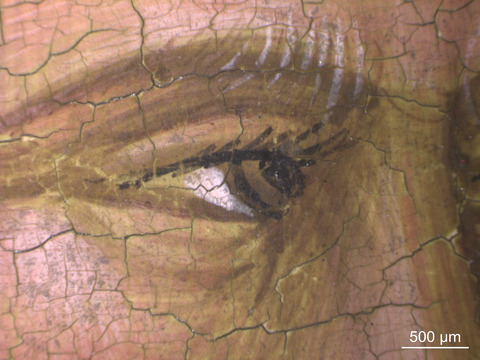

The skin paint follows the same technique as seen on the St. Mary Magdalene panel, beginning with toning the shadows with a green verdaccio and then applying small, precise brush strokes of pink skin paint to build up the forms of the hands and face. Much like on the St. Mary Magdalene panel, detailing of the hands and features of St. Catherine, as well as the contours of the neck and face, were carried out last with a brown paint (tech. fig. 43). The eye is articulated using a dark black paint to create the pupil, iris, and eyelid (tech. fig. 44).

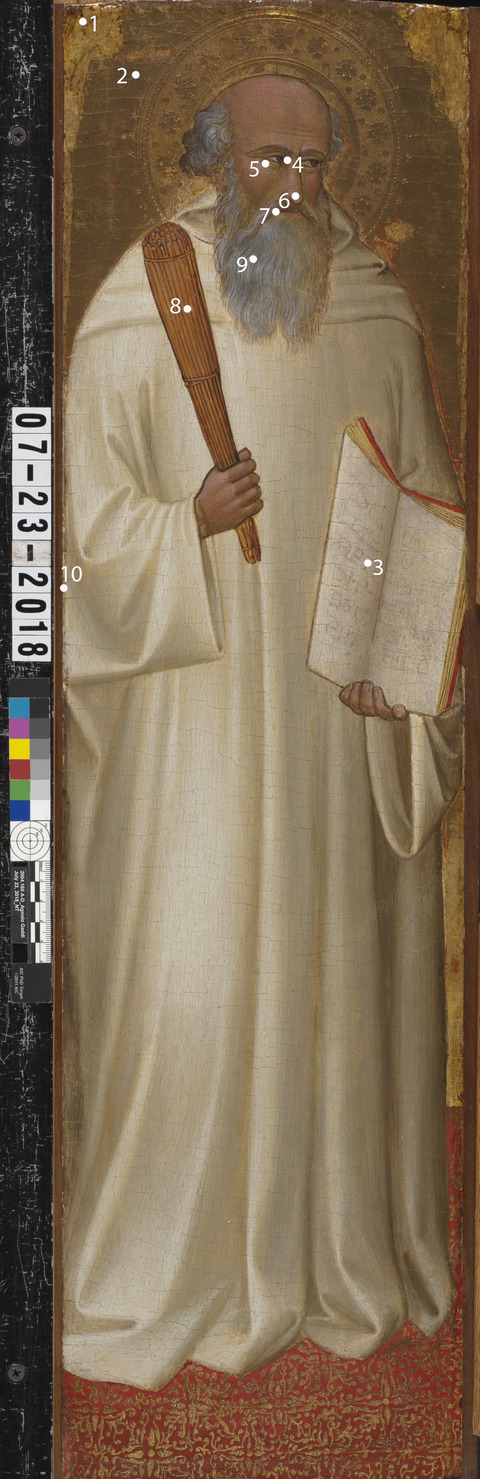

St. Benedict (C):

The palette used on St. Benedict is the most limited of the four panels, composed primarily of whites, grays, and browns with a few splashes of red (tech. fig. 45). The paint was applied following the incision lines that established the composition. Following the recommendations of Cennini, the robes were painted before the hands and skin, as can be observed on the proper right sleeve where the line used to outline the robe can be seen beneath the saint’s wrist.

The drapery was applied in three tones using a brown for the shadows, a gray for the midtones, and a bright white for the highlights (tech. fig. 46). In some areas the transitions from shadow to highlight were applied directly to the ground while in other areas the shadow color is applied over the midtone and functions more as an outline.

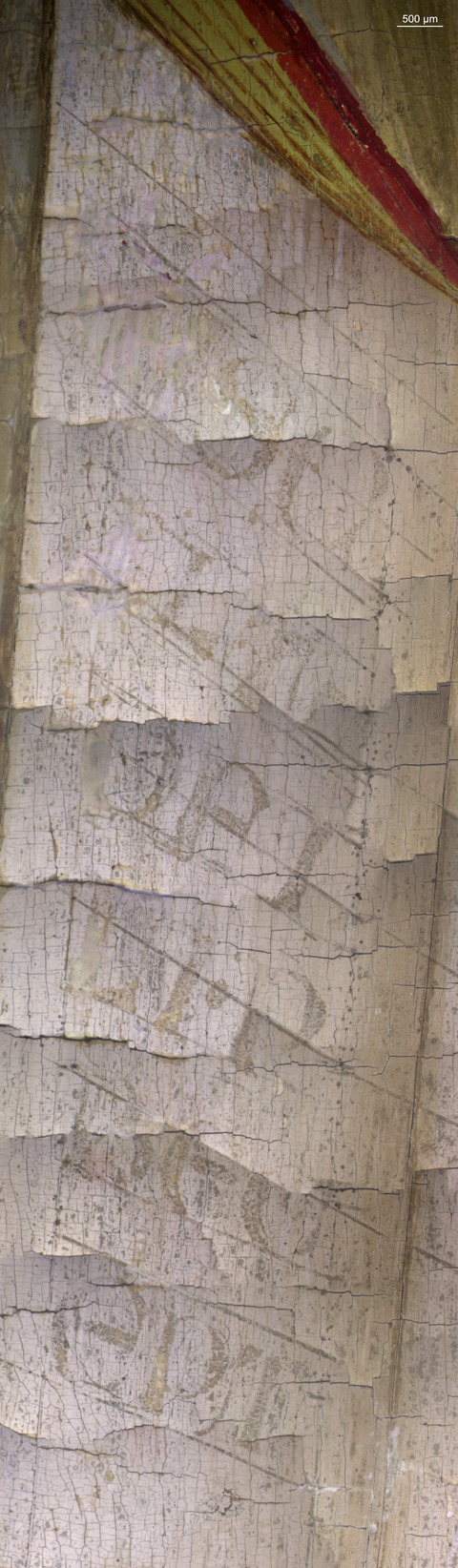

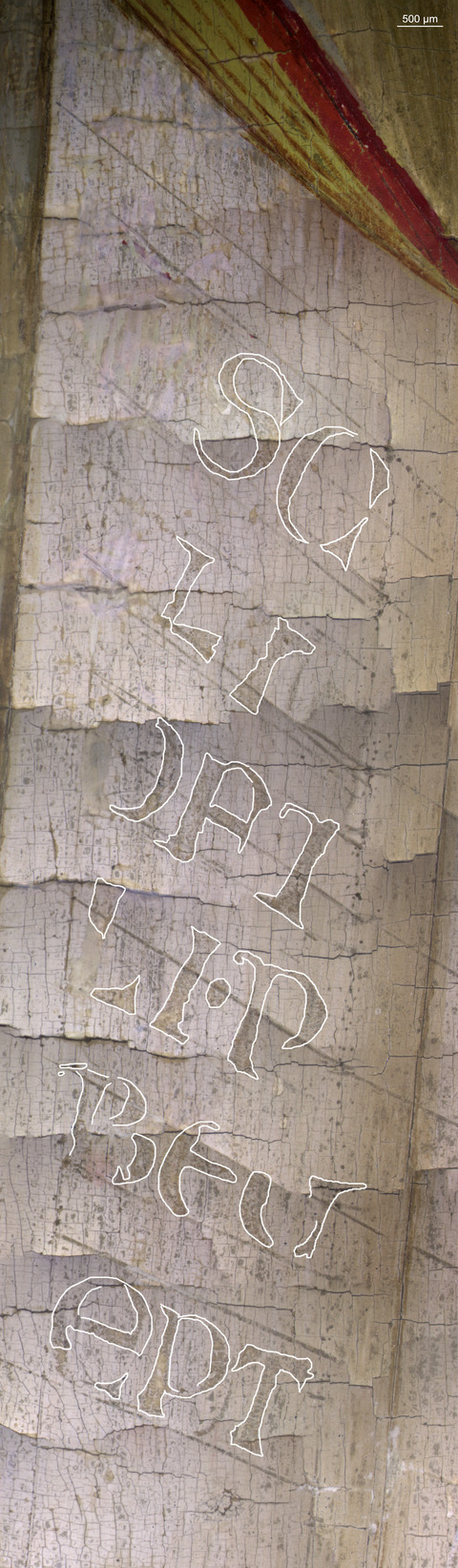

The contours of the book were incised into the ground before painting began to establish the perspective of the book and the lines of text. Red paint follows the incision lines to create the cover of the book. Carefully articulated gray lettering, which appears to have been stenciled, is also visible on the pages of the book (tech. figs. 47, 48). Although abraded, the remains of the inscription suggest it displays lines from the Rule of St. Benedict.21

As prescribed by Cennini in his instructions for painting an old man in fresco, the artist of this panel appears to have used a darker verdaccio than on the female saints, where a light green color was chosen.22 The verdaccio is left exposed in the shadows of the man’s face while the midtones and highlights were painted using short strokes of pink and white paint. The skin on St. Benedict’s face is markedly redder,23 and white highlights are used more sparingly than on the female saints. Outlining in brown is present on the hands, features, and outlines of the figure. Over the brown outlining, a few strokes of white paint were used to create the man’s bushy eyebrows and a few strokes of hair on the top of his head (tech. fig. 49).

The shadows of the beard and the hair were painted using the same tone as used on the verdaccio and were likely applied when the shadows of the face were painted. The gray midtones and highlights were painted using thin, undulating strokes of paint.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux (D)

Much like the St. Benedict panel, the St. Bernard panel contains a relatively limited palette of grays, whites, and browns with the addition of a large passage of a bluish-black book and some bright red ribbons (tech. fig. 50). The paint was applied following the incision lines that established the composition beginning with the robes, then the book, and lastly the face and hands.

The drapery is painted using the same color palette and same technique as on the St. Benedict panel. The contours of the robes were created using three tones: a brown for the shadows, a gray for the midtones, and a bright white for the highlights.

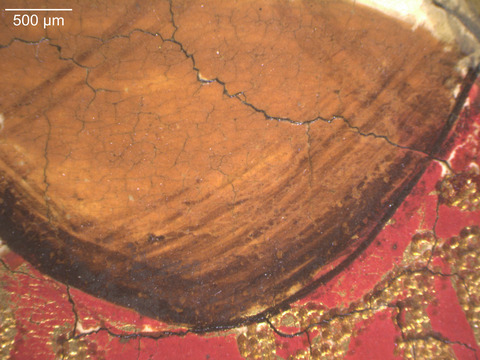

The skin painting also followed the same process as on the St. Benedict panel using a greenish-brown verdaccio to create the shadows in the skin and a range of ruddy tones for the midtones and highlights. Abrasion has left large portions of the verdaccio exposed especially in the area where the skin transitions to the beard.

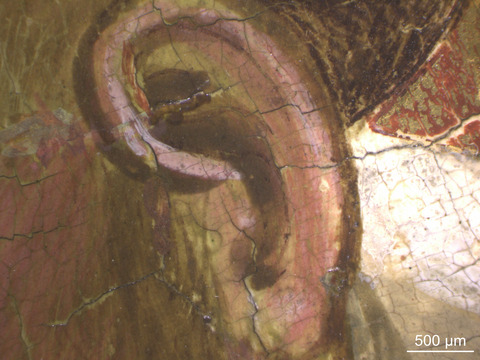

Outlining in brown is present on the hands, features, and outlines of the figure. The ear is painted using a brown outlining followed by a midtone pink and dashes of light pink highlights (tech. fig. 51). A single stroke of black paint is used to create the upper eyelid, with another stroke for the lower eyelid (tech. fig. 52). Individual strokes of black paint radiate down from the upper eyelid creating long black eyelashes that create the effect of the saint looking steadily down at his book.

The beard is painted more simplistically than St. Benedict’s beard using a single tone of brown that is used for the outlining. The patches of hair on the saint’s tonsure are underpainted with the greenish-brown verdaccio and detailed with strokes of brown outlining.

Mordant Gilding:

Mordant gilding was applied over the paint layer on all of the panels except for St. Benedict. Elaborate decorative borders on St. Catherine and St. Mary Magdalene’s robes were created using what appears to be oil mordant pigmented with lead white, as is described by Cennini.24 Over the mordant, small pieces of gold leaf were applied to create decorative lines. A similar technique was used on the cover of St. Bernard’s book and the straps of St. Catherine’s book. St. Mary Magdalene’s box of ointment, which she holds in her proper left hand, also appears to have been mordant gilded as no red bole layer is visible through abrasion in the gold. XRF analysis detected a strong peak for lead in this area but only a trace of iron, suggesting the presence of a mordant containing lead white (see XRF analysis: St. Mary Magdalene, sample 10). Notably, analysis of the mordant using XRF did not detect copper, suggesting the artist did not follow Cennini’s recommendation of adding verdigris to the lead white mordant to speed drying. This may be due to the desire to have the mordant last longer, as Cennini recommends not adding any verdigris if the mordant is to be used over more than four days.25

Painting Tools:

Small to medium-sized brushes, burnishing tools, punches, pointed tools for making incisions

Binding Media:

Egg tempera (untested)

Color Palette:

The panels are painted with a colorful palette composed of a range of yellows, reds, blues, pinks, whites, grays, browns, and greens against a glittering gold background. Several analytical techniques, including Raman microspectroscopy, SEM-EDS, and XRF (tech. figs. 67–70) were used to identify pigments that were consistent with those described by Cennini. Cross-section samples were taken from three locations on the St. Catherine panel (tech. fig. 53) in addition to that taken from the St. Benedict panel (tech. fig. 7). Lead-tin yellow II (identified by Cennini as giallolino),26 yellow ocher, vermilion, ultramarine blue, azurite, red earth (hematite), and red lake pigments were confirmed using these techniques.

Red/pink

Vermilion and red earth (hematite) were confirmed using SEM-EDS analysis and Raman micro-spectroscopy. Mercury was identified using XRF on all four panels, suggesting the widespread use of vermilion. Vermilion was used in the sgraffito (see tech. fig. 33) that forms the ground plane behind St. Catherine, St. Bernard, and St. Benedict and to paint the robe of St. Mary Magdalene. It was also used to articulate the red outlines on the books held by the saints. The presence of mercury in the skin of both the male and female saints suggests the generous use of vermilion in these areas as well.

Using Raman microspectroscopy, a red earth pigment (hematite) was identified on the spine of the book held by St. Catherine. This dark red color was used to differentiate the shadow of the book’s spine from the cover, which contains vermilion. Red earth was also used to delineate the pages of the book. This differentiation of pigments to paint the highlights of the book’s cover and the shadows of the book’s spine is significant in that is shows the artist’s intentionality with materials.

St. Catherine’s pink robe was likely painted using a red lake pigment glaze, which has likely undergone some degree of fading. SEM-EDS analysis identified the presence of aluminum in a large red lake pigment particle, as well as distributed throughout the pink paint layers (tech. fig. 54), suggesting the red dye was precipitated onto an aluminum substrate. Lead was also present throughout the paint layers suggesting the lake was mixed with lead white in varying proportions as the layers of paint were built up. Layer four is especially lead rich, while layers two and five contain almost no lead but do contain aluminum (tech. figs. 54–57).

Yellow

Lead-tin yellow and yellow ocher were identified on the lining of St. Catherine’s robe using Raman microspectroscopy. Lead-tin yellow, possibly mixed with lead white, was used to create the bright, vibrant highlights of the robe. The warm orange yellow ocher was used to paint the shadows in the folds of the saint’s robe. Just as the artist used distinct pigments to differentiate the highlights and shadows on the book, the artist appears to have used a different pigment for the highlights and shadows of the robe. This contradicts the description given by Cennini, albeit for fresco painting, in which shadows are created using a pure color and midtones and highlights are created by simply adding white.27

Green

The pigments in the green lining of the robe on the St. Mary Magdalene panel were analyzed using Raman microspectroscopy. Lead-tin yellow II and azurite were identified, suggesting a mixture was used to create the vibrant green tones. Although it is possible that some lead white is also present in this mixture, the EDS mapping of lead appears to correspond quite closely to the EDS mapping of tin, suggesting little, if any, lead white was used. The same combination was used on St. Catherine’s dress, as confirmed by SEM-EDS analysis of a cross section from this area (tech. figs. 58–61). Cennini describes this combination as being good for use in both fresco and panel painting.28

Iron was detected in St. Mary Magdalene’s face where a green verdaccio was used to create the shadow (see XRF Analysis: St. Mary Magdalene sample 1). Traces of potassium are also present, which may be indicative of a green earth pigment. This suggests the use of a green earth in the verdaccio, as recommended by Cennini.

Blue

Blue as a pure color is not widely employed on the panels. Swatches of blue are present only on the inner sleeve and tiara of the St. Catherine panel. The pigment on the inner sleeve was identified as ultramarine using Raman microspectroscopy.

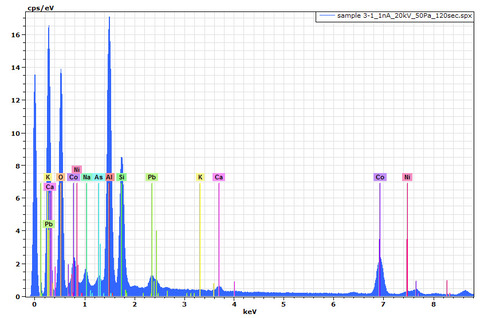

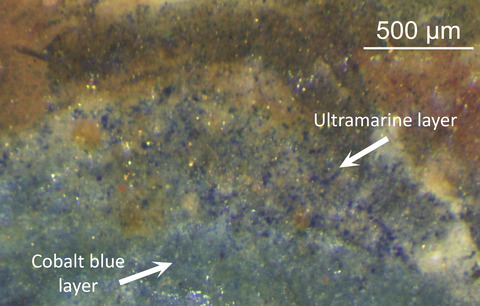

XRF detected cobalt in the tiara suggesting the presence of smalt or cobalt blue. A scraping of the area was analyzed using SEM-EDS and the presence of cobalt (tech. figs. 62, 64, 65) and aluminum (tech. fig. 63) were confirmed. Raman spectroscopy confirmed the presence of cobalt blue (cobalt aluminate) in the scraping. Ultramarine was also identified in the scraping suggesting the tiara was originally painted using ultramarine, the same pigment used on the inner sleeve. Later, this area appears to have been overpainted with cobalt blue (cobalt aluminate). Microscopy confirmed this layer structure (tech. fig. 66). It is unclear why this area, and no others, was overpainted early in the panel’s history, although it can be hypothesized that damage to this area necessitated the overpainting.

Azurite was not identified in the pure passages of blue but was identified in areas of green using Raman microspectroscopy (see above).

Brown

Brown was used in the hair and beard of St. Bernard as well as the rock formation on which St. Mary Magdalene stands. Outlining of the hands, faces, and attributes on all four panels are also carried out with brown pigments. Brown areas on the St. Mary Magdalene panel were analyzed using XRF (see XRF Analysis: St. Mary Magdalene samples 8, 13, 14). Both iron and manganese were identified in passages of brown suggesting the use of iron-oxide earth pigments including umber. Interestingly, significant peaks for zinc were consistently identified in areas suggesting the possibility that the pigments were made from areas with large concentrations of zinc.29

Black

Black is used for outlining on the saint’s eyes and eyelashes as well as in the fillet of St. Mary Magdalene, the books held by St. Bernard and St. Catherine, and for outlining on some of the attributes. Black was also mixed into St. Benedict’s gray beard. XRF analysis of these areas suggests the likely use of carbon black, as there was no phosphorous identified therefore it is not bone black (table 3, sample 9).

White

Lead was identified in nearly all XRF spectra. In some cases, lead is associated with tin and can be attributed to the presence of lead-tin yellow II, but in other cases no tin is present, suggesting the widespread use of lead white. Lead white appears to have been used to paint skin tones, the robes of the male saints, St. Benedict’s beard, and highlights in the drapery of St. Catherine.

XRF Analysis:

St. Mary Magdalene

| Sample | Location | Elements | Possible Pigments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Skin shadow (11.5 cm down 10.5 cm from left) | Major: Fe, Pb Minor: Trace: Ca, Hg, Sr, K, Cu, Zn | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments, likely including a green earth), lead white, trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of vermilion. |

| 2 | Cheek (9.5 cm down 10.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Hg Trace: Fe, Ca, Sr | Lead white, vermilion, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 3 | Orange hair (11.5 cm down 8 cm from right) | Major: Pb Minor: Fe Trace: Ca, Sr, Sn, Zn | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of lead-tin yellow. |

| 4 | Yellow strand of hair (11.5 cm down 8 cm from right) | Major: Pb Minor: Ca, Fe Trace: Sr, Sn, Zn | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of lead-tin yellow. |

| 5 | Green drapery highlight (24.4 cm down 10 cm from right) | Major: Cu, Pb Minor: Trace: Fe, Sr, Ca, Sn, Hg | Azurite (as identified with Raman), lead-tin yellow (as identified with Raman), possibly lead white, iron-oxide (earth pigments), calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of vermilion. |

| 6 | Green drapery shadow (24.5 cm down 10.5 cm from right) | Major: Cu, Pb Minor: Fe Trace: Sr, Ca, Sn, Hg | Azurite (as identified with Raman), lead-tin yellow (as identified with Raman), possibly lead white, iron-oxide (earth pigments), calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of vermilion. |

| 7 | Red robe highlight (28 cm down 10 cm from right) | Major: Hg, Pb Minor: Trace: Fe, Ca, Sn, Cu | Vermilion (as identified with Raman), lead-tin yellow, possibly lead white, trace of iron-oxide (earth pigments), calcium-containing ground, trace of lead-tin yellow, trace of copper containing blue and/or green pigment. |

| 8 | Brown rock (59 cm down 4 cm from left) | Major: Fe, Pb Minor: Zn Trace: Ca, Sr, Cu, Mn, Hg | Iron-oxide (earth pigments including umber), lead white, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper containing blue and/or green pigment, trace of vermilion. |

| 9 | Mordant gilding over red robe (56 cm down 6 cm from right) | Major: Hg, Pb, Au Minor: Trace: Fe, Ca, Sr | Shell gold, vermilion, lead white-containing mordant, lead-tin yellow, trace of iron-oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 10 | Black outline on gold box (24 cm down 4 cm from right) | Major: Au, Pb Minor: Trace: Fe, Ca, Sr | Likely carbon black, shell gold, lead white-containing mordant, trace of iron-oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 11 | Green tree (40 cm down 17.5 from right) | Major: Cu, Fe, Ca Minor: Pb, Sr Trace: K, Hg, Mn, Zn | Copper containing blue and/or green pigment, iron-oxide (earth pigments including umber), lead white, calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 12 | Yellow highlight on green tree (41 cm down 17.5 cm from right) | Major: Cu, Pb Minor: Fe Trace: Ca, Sr, Sn, K, Hg, Zn | Copper containing blue and/or green pigment, lead-tin yellow, lead white, iron-oxide (earth pigments including umber), calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of vermilion. |

| 13 | Tree outline (53.5 cm down 17 cm from right) | Major: Fe, Pb Minor: Ca, Sr, Zn Trace: Cu, Hg, Mn | Iron-oxide (earth pigments including umber), lead white, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of vermilion, trace of copper containing blue and/or green pigment. |

| 14 | Brown tree (53 cm down 17 cm from right) | Major: Fe, Pb, Ca Minor: Sr, Zn Trace: Cu, Hg, Mn | Iron-oxide (earth pigments including umber), lead white, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of vermilion, trace of copper containing blue and/or green pigment |

| 15 | Bole (1.5 cm down 16 cm from right) | Major: Fe, Ca, Sr Minor: Pb, Ti Trace: Cu, Mn, K | Iron-oxide containing bole with natural titanium component, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), lead white. Aluminosilicates were also identified in this layer using SEM/EDS analysis. |

Table 2: Results of X-ray fluorescence analysis conducted with a Bruker Artax microfocus XRF with rhodium tube, silicon-drift detector, and polycapillary focusing lens (~100μm spot).

*Major, minor, trace quantities are based on XRF signal strength not quantitative analysis

St. Benedict

| Sample | Location | Elements | Possible Pigments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gold restoration (1.5 cm down 2 cm from left) | Major: Au, Fe, Ca, Sr Minor: Cu Trace: Pb, Ba, K | Gold/copper alloy leaf, iron-oxide containing bole, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of lead white, barium from modern restoration material. |

| 2 | Gilding (3.5 cm down 4.5 cm from left) | Major: Au, Fe, Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Ti, K, Pb, Mn | Gold leaf, iron-oxide containing bole (with titanium content), calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of lead white. |

| 3 | Letter on book (27.5 cm down 16 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Fe, Ca, Sr, Zn | Lead white, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with trace of strontium). |

| 4 | Shadow on eye (8 cm down 12 cm from left) | Major: Pb, Fe Minor: Hg, Ca, Sr Trace: Cu, Zn, K | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments including possibly green earth), vermilion, copper containing green and/or blue pigment, calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 5 | Skin midtone (8 cm down 11 cm from left) | Major: Pb, Fe Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Hg, Cu, Zn, K | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), vermilion, copper containing green and/or blue pigment, calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 6 | Skin highlight (9.5 cm down 12.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Fe, Hg Trace: Ca, Sr, Cu | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), vermilion, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 7 | Mouth outline (10.4cm down 11.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb, Fe Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Hg, Cu, K, Mn | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of vermilion, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment. |

| 8 | Orange brush (14.3 cm down 7.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb, Fe Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Cu, K, Mn, Zn, Ba, Cd | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of barium and cadmium red, yellow, or orange from retouching. |

| 9 | Beard (13 cm down 10 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Fe Trace: Cu, Ca, Sr, Zn | Lead white, likely carbon black, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment. |

| 10 | Ground (27.5 cm down 1 cm from left) | Major: Ca Minor: Pb Sr Trace: Fe, Zn | Calcium-containing ground (with strontium), lead white, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments). |

Table 3: Results of X-ray fluorescence analysis conducted with a Bruker Artax microfocus XRF with rhodium tube, silicon-drift detector, and polycapillary focusing lens (~100μm spot).

*Major, minor, trace quantities are based on XRF signal strength not quantitative analysis

St. Bernard of Clairvaux

| Sample | Location | Elements | Possible Pigments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ground (64 cm down 20.5 cm from left) | Major: Ca Minor: Pb Sr Trace: Fe, Zn, Ba | Calcium-containing ground (with strontium), lead white, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments). The presence of barium suggests this area may be a modern restoration. |

| 2 | Book (20.5 cm down 14.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Fe, Ca, Sr Trace: K, Zn, Hg, Cu | Lead white, likely carbon black, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of vermilion, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment. |

| 3 | Mordant gilding on book (23 cm down 14 cm from left) | Major: Pb, Au Minor: Trace: Fe, Ca, Sr | Lead white mordant, shell gold, likely carbon black, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with trace of strontium). |

| 4 | Red ribbon on book (19.5 cm down 12 cm from left) | Major: Hg, Pb Minor: Trace: Ca, Sr, Fe, Cu | Vermilion, lead white, trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium), small trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment. |

| 5 | Gilding (7.4 cm down 2.3 cm from left) | Major: Au, Fe Minor: Trace: Ca, Sr, Pb, Ti, Mn | Gold leaf, iron-oxide containing bole, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of lead white. |

| 6 | Gold restoration (7.5 cm down 1.8 cm from left) | Major: Au, Fe, Ca, Sr Minor: Cu Trace: Pb, Ba | Gold/copper alloy leaf, iron-oxide (earth pigments) from bole, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of lead white, barium from modern restoration material. |

Table 4: Results of X-ray fluorescence analysis conducted with a Bruker Artax microfocus XRF with rhodium tube, silicon-drift detector, and polycapillary focusing lens (~100μm spot).

*Major, minor, trace quantities are based on XRF signal strength not quantitative analysis

St. Catherine

| Sample | Location | Elements | Possible Pigments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ground (24 cm down 1 cm from left) | Major: Ca Minor: Sr Trace: Pb, Fe Zn, Cu | Calcium-containing ground (with strontium), traces of iron oxide (earth pigments) and lead white. |

| 2 | Forehead (7 cm down 10.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Fe, Hg Trace: Ca, Sr | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), vermilion, calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 3 | Cheek (10 cm down 12.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb Hg Minor: Fe, Sr Trace: Ca, Cu | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), vermilion, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper-containing green or blue pigment. |

| 4 | Hair (7.5 cm down 14 cm from left) | Major: Pb, Fe Minor: Sr, Ca Trace: Cu, Zn, Sn | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of lead-tin yellow, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper-containing green or blue pigment. |

| 5 | Gilding (8.5 cm down 17.5 cm from left) | Major: Au, Fe Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Ti | Gold leaf, iron-oxide containing bole, calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 6 | Gold restoration (5.5 cm down 18.5 cm from left) | Major: Au, Fe Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Cu, Pb, Ti, K | Gold/copper alloy leaf, iron-oxide containing bole, calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 7 | Yellow sleeve (24 cm down 3.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Ca, Sr, Sn, Fe, Cu | Lead-tin yellow (confirmed with Raman microspectroscopy), possibly lead white, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), calcium-containing ground with strontium, trace of copper-containing green or blue pigment. |

| 8 | Blue inner sleeve (26 cm down 4 cm from left) | Major: Cu, Fe, Pb Minor: Ca, Sr, Hg Trace: K | Ultramarine (confirmed Raman micro-spectroscopy), azurite, iron oxide (earth pigments), lead white, vermilion, calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 9 | Green dress (25 cm down 13 cm from left) | Major: Cu, Pb, Ca, Hg, Sr Minor: Fe, Sr Trace: K | Azurite (confirmed Raman micro-spectroscopy), lead-tin yellow (confirmed Raman micro-spectroscopy), possibly lead white, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium-containing ground (with strontium). |

| 10 | Red robe shadow (15.5 cm down 4.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Ca, Sr, Hg, Cu, Fe | Likely a red lake pigment, lead white, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of vermilion, trace of copper-containing green or blue pigment. |

| 11 | Red sgraffito (70 cm down 4 cm from left) | Major: Hg, Au Minor: Pb, Fe Trace: Ca, Sr, Cu | Vermilion, gold leaf, lead white, iron-oxide containing bole, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper containing green or blue. |

| 12 | Black line on wheel (69 cm down 7 cm from left) | Major: Fe, Pb Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Hg, Au, Mn | Lead white, likely carbon black pigment, iron-oxide (earth pigments including umber), calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of vermilion, trace of gold. |

| 13 | Red line on book (30.5 cm down 9.5 cm from left) | Major: Fe, Pb Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Sn, Cu, Zn | Iron oxide (earth pigments), lead white, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of lead-tin yellow, trace of copper containing green or blue. |

| 14 | Red on book spine (33.5 cm down 9.5 cm from left) | Major: Fe Minor: Ca, Sr, Pb Trace: Cu, Zn | Red earth/hematite (confirmed Raman micro-spectroscopy), lead white, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper containing green or blue. |

| 15 | Orange shadow on cloak (29 cm down 6 cm from left) | Major: Fe, Pb Minor: Ca, Sr Trace: Cu, Zn, Sn, Mn | Iron oxide (earth pigments including umber), lead white, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of lead-tin yellow, trace of copper containing green or blue. |

| 16 | Orange hair beside tiara (4.5 cm down 11 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Fe, Sn Trace: Ca, Sr, Cu, Zn, Mn | Iron oxide (earth pigments including umber), lead white, lead-tin yellow, calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper containing green or blue. |

| 17 | Blue tiara (4.5 cm down 9.5 cm from left) | Major: Pb Minor: Fe, Co, Ca, Sr, Cu Trace: As, Ni | Cobalt blue (confirmed Raman microspectroscopy), ultramarine (confirmed Raman microspectroscopy), lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), calcium-containing ground (with strontium), trace of copper containing green or blue. |

Table 5: Results of X-ray fluorescence analysis conducted with a Bruker Artax microfocus XRF with rhodium tube, silicon-drift detector, and polycapillary focusing lens (~100μm spot).

*Major, minor, trace quantities are based on XRF signal strength not quantitative analysis

Surface Appearance:

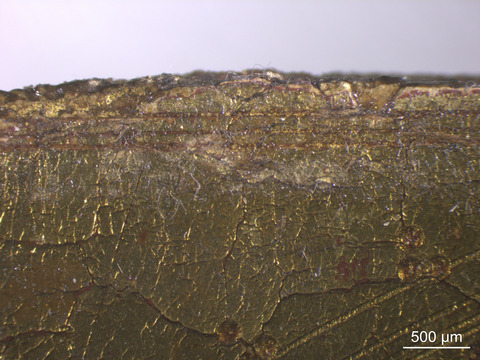

There is little texture to the paint surface of the panels. There is, however, a prominent craquelure across the surface of the paint and gilding. The gilded halos and areas of sgraffito have surface texture from the punchwork in the gold.

Condition of Paint/Gilding

The paint layer and gilding on the panels are in generally good condition. The paint layer is structurally stable despite a prominent craquelure pattern. There are small losses to the paint layer across all four panels, as well as two large losses on the left edge of the St. Catherine panel. The lower section of St. Catherine’s green robe has also sustained significant damage. There is also a large loss to the halo on the St. Catherine panel. There is an area of damage along a large crack at the bottom edge of the St. Bernard panel as well as on the saint’s proper right shoulder and the cover of the book. The condition of the paint layer is abraded on the faces of the male saints, where pinpoint losses in the faces have disrupted the delicate strokes of paint used to depict the figures.

Restoration gilding composed of a gold/copper alloy (see XRF analysis, Tables 2–5) is present on the upper corners of all four panels. This gilding can be identified in the infrared reflectograms of the panels (tech. figs. 16–19). It appears that some of this restoration gilding extends over original paint.

Description of Varnish/Surface Coating

Analyzed Observed Documented

| Type of Varnish | Application |

|---|---|

| Natural resin | Spray applied |

| Synthetic resin/other | Brush applied |

| Multiple Layers observed | Undetermined |

| No coating detected |

The panels have not been treated since coming to the IMA on long-term loan in 1971. There is a thick coating of what appears to be synthetic varnish on all four panels (tech. figs. 71–74). The paintings appear to have been retouched using synthetic resins, suggesting they were last treated in 1958 (see Summary of Treatment History). Retouching is present over scattered losses and along the edges of all four panels. The bottom and right edges of the St. Mary Magdalene panel have been extended with retouching. An extensive passage of retouching is present at the bottom of St. Catherine’s green robe and along the top of her halo where a large loss is present.

Condition of Varnish/Surface Coating

The surface coatings are in generally acceptable condition. The varnish is mostly clear and saturating, although there are a few localized areas on the St. Catherine panel where the varnish has slightly blanched. The retouching is generally well-matched, although easily identifiable when viewed under a microscope.

Description of Frame

Original/first frame

Period frame

Authenticity cannot be determined at this time/ further art historical research necessary

Reproduction frame (fabricated in the style of)

Replica frame (copy of an existing period frame)

Modern frame

The frame is a reproduction frame in a neo-Gothic style (tech. fig. 75). The frame is carved wood with a water gilded surface. Recessed elements of the frame are painted with a gray color. The frame roughly imitates the appearance of the engaged frames of a Gothic altarpiece.

Frame Dimensions:

Outside frame dimensions: 112.6 × 104.3 cm

Sight size:

| Height (cm) | Width (cm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Far left panel | 72 | 17.7 |

| Left center panel | 72 | 19.7 |

| Right center panel | 72 | 19.7 |

| Far right panel | 72 | 17.7 |

Table 6: Sight size dimensions

Rebate dimensions:

| Height (cm) | Width (cm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Far left panel | 73.7 | 20 |

| Left center panel | 74.7 | 21.5 |

| Right center panel | 74.2 | 21.7 |

| Far right panel | 74 | 20.4 |

Table 7: Rebate dimensions

Distinguishing Marks:

Item 13. Paper label (with red border), upper-left side “6734/27” (tech. fig. 76).

Item 14. Inscription, chalk, top edge “1883” (tech. fig. 76).

Item 15. Paper label, upper-right side “T.R. #/ 10042” (tech. fig. 76).

Condition of Frame

The frame is in structurally stable condition. The gilding and paint on the frame are in stable condition.

Notes

-

Letter from Edward O. Korany to Newhouse Galleries, 15 March 1958, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Paul A.J. Spheeris, “Conservation Report on the Condition of the Clowes Collection,” 25 October 1971, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Martin Radecki, Clowes Collection condition assessment, undated (after October 1971), Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Ian Tyers, “Tree-Ring Analysis and Wood Identification of Paintings from the Indianapolis Museum of Art: Dendrochronological Consultancy Report 1082,” January 2019, p. 32, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Personal communication with Dillian Gordon. For an example, see https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/learn-about-art/the-anatomy-of-an-altarpiece-the-polyptych. ↩︎

-

To minimize sampling, the ground layer has been analyzed using a cross section from a damage on the X panel. Preparation methods for the other panels have been extrapolated from this information. ↩︎

-

Examples of pilaster panels with decorative punchwork around the edge of the engaged frame have been attributed to Jacopo di Cione and are now in the collection of the National Gallery in London. See Dillian Gordon, National Gallery Catalogues: The Italian Paintings before 1400 (London: National Gallery Company Ltd., 2011), 96–97. For images, see https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/jacopo-di-cione. This technique can also be observed in the pinnacles of the Agnolo Gaddi altarpiece Madonna and Child with Saints Andrew, Benedict, Bernard, and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels in the National Gallery of Art, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.206122.html. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 70–73. ↩︎

-

Elvacite 2040 (synthetic resin) was used to fill the cradle while shooting the X-radiograph so that the appearance of the cradle would be minimized in the X-radiograph and allow the composition to be better interpreted. ↩︎

-

Dillian Gordon, National Gallery Catalogues: The Italian Paintings before 1400 (London: National Gallery Company Ltd, 2011), 222. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 70–73. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 85–86. ↩︎

-

Erling Skaug, Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430 (Oslo: IIC Nordic Group, Norwegian Section, 1994), 2: §8.2. ↩︎

-

Skaug asserts that the same punch was used on panels from the Göttingen University collection. Erling Skaug, Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430 (Oslo: IIC Nordic Group, Norwegian Section, 1994), 1:263; 2: §8.2. ↩︎

-

For transfer technique see David Bomford et al. Art in the Making: Italian Painting before 1400 (London: National Gallery Publications Ltd., 1989), 135. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 88-89. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 91–92. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 46. ↩︎

-

Similar outlining is described by Cennini in his fresco painting instructions. See Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 47. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 91–92. ↩︎

-

We are grateful to Dr. Dillian Gordon for deciphering this inscription. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte) trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 47. ↩︎

-

The “redness” of the aged person is commented on by Cennini when he recommends the use of eggs from farm hens for this purpose. Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 93–94. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 96. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 96–97. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 28. See also David Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Italian Painting before 1400 (London: National Gallery Publications Ltd., 1989), 37. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 49-50. ↩︎

-

Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte), trans. Daniel V. Thompson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1936), 32. ↩︎

-

This has been identified on other artworks from the area of Florence, and it has been hypothesized that zinc deposits present in the earth in these areas lead to zinc content in iron-oxide earth pigments. Interestingly, no zinc was identified in the iron-rich bole layer. Ezio Buzzegoli, Diane Kunzelman, Pietro Moioli, and Claudio Seccaroni, “Indagini Sui Dipinti per La Camera Borgherini,” OPD Restauro, no. 25 (2013): 164, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24398131. ↩︎

Additional Images