Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

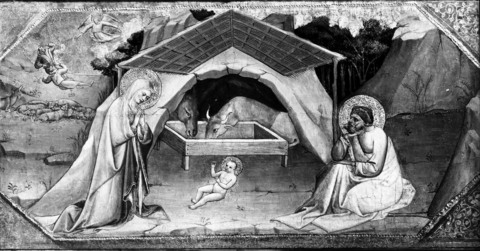

This small Nativity depicts the adoration of the Christ child. Sheltered under a lean-to attached to a cave, the newborn baby rests on the ground. Jesus’s body is illuminated by rays of heavenly light, and his halo features a cruciform design, which presages the cross on which he will die. Mary kneels before him in awe and admiration, welcoming both her child and the Son of God into the world, while Joseph stands meekly, holding his cap and bowing his head. Behind a trough, a donkey and ox—beasts of burden—bear humble witness to the Christ child’s divinity. Framing the scene, an architectural structure sits on the left, and on the right, a hilly landscape recedes into the distance. The night sky is filled with golden stars and a crescent moon that embodies the quiet yet miraculous moment. An angel hovers in the sky pointing to the scene below. Every figure in the painting, including the animals, quietly directs the viewer to join them in beholding Christ.

The size and format of this painting indicate that it was originally a

predella panel for a fifteenth-century Tuscan altarpiece. In unpublished documents from the 1930s, the Austrian art historians William Suida, Gustav Glück, and Robert Eigenberger each attribute the panel to Fra Angelico (1395–1455), citing two other

Nativity scenes by that artist as evidence:

a fresco in San Marco, Florence (fig. 1); and another predella panel, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, now attributed to his student Zanobi Strozzi (1412–1468) (fig. 2). Also in the 1930s, the Italian art historian Lionello Venturi suggested the painting may be the work of Domenico di Michelino (1417–1491), another Fra Angelico student whose work is often mistaken for that of Zanobi Strozzi.

In 1942, the art historian Erwin Panofsky noted its similarity to a work by Lorenzo Monaco (about 1370–1425) and suggested that the panel was likely by that artist.

Figure 1: Fra Angelico (Italian, 1390–1455), Nativity, 1440–1445, fresco in the convent of San Marco, 75-63/64 × 64-49/64 in. Museo di San Marco, Florence, Italy. Photo Credit: Alfredo Dagli Orti / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 1: Fra Angelico (Italian, 1390–1455), Nativity, 1440–1445, fresco in the convent of San Marco, 75-63/64 × 64-49/64 in. Museo di San Marco, Florence, Italy. Photo Credit: Alfredo Dagli Orti / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 2: Attributed to Zanobi Strozzi (Italian, 1412–1468), The Nativity, about 1433–1434, tempera and gold on wood, 7-3/8 × 17-1/8 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of May Dougherty King, 1983, 1983.490.

Figure 2: Attributed to Zanobi Strozzi (Italian, 1412–1468), The Nativity, about 1433–1434, tempera and gold on wood, 7-3/8 × 17-1/8 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of May Dougherty King, 1983, 1983.490.

In 1934, conservators from the Fogg Art Museum examined the panel and reported that it had been extensively abraded and repainted, particularly the area of the sky. Without removing the added layers of paint and varnish, the original image and brushwork cannot be clearly assessed. Regardless, the overpainting does not dramatically alter the basic composition, which belongs within the school of Fra Angelico.

The facts of Fra Angelico’s life are unclear. Born Guido di Pietro in approximately 1395, he spent his life as both a painter and a friar. He joined the Confraternity of San Nicola da Bari in 1417, where he was listed as a painter, and the Dominican Order, likely in Fiesole, by 1419, after which he was called Fra (brother) Giovanni di Fiesole. As he became a prolific artist, he was often known as Fra Giovanni Angelico, and in Italy he is referred to as Beato (blessed) Angelico, a title made official by Pope John Paul II in 1982.

At some point, the artist likely spent time in the workshop of Lorenzo Monaco. Later, in his own studio, Fra Angelico trained such notable artists as Zanobi Strozzi, Domenico di Michelino, Pesellino (about 1422–1457), and Benozzo Gozzoli (about 1421–1497). While he worked primarily throughout Tuscany, Fra Angelico also worked in Orvieto and the Vatican with Gozzoli in the late 1440s. He is perhaps best known for his nearly 50 frescoes for the San Marco Convent in Florence (1439–1443), a project in which Gozzoli also likely participated. Scholars have studied these works for evidence of Fra Angelico’s spiritual dedication—as was manifest in his paintings—often focusing on the contemplative nature of each image.

Due to the dating and the similarities between this

Nativity and the works of Lorenzo Monaco, Fra Angelico, and his students, it may be safely placed within the school of Fra Angelico. Early examples attributed to Lorenzo Monaco or his school serve as predecessors for the Clowes panel. Lorenzo’s

Nativity in the Staatliche Museum, Berlin, depicts the Holy Family next to a freestanding, roofed structure that closely resembles the lean-to in the Clowes

Nativity (fig. 3). Both sheds are constructed of wooden branches that support a pitched roof of wooden planks. Each also includes a rudimentary, red architectural structure with cracks in the walls to the left of the Holy Family. Another

Nativity from the school of Lorenzo Monaco takes the freestanding structure and places it against a cave, but removes the additional support crossbars (Rome, Vatican Museums) (fig. 4). Unlike the Berlin

Nativity, the one in the Vatican depicts Joseph wearing a cap similar to the one he is holding in the Clowes panel. Also like the Clowes

Nativity, the one in the Vatican places the recumbent Christ child on the ground before his kneeling mother, and the two animals in the back are slightly obscured by the trough.

Figure 3: Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, about 1370–1425), Nativity, about 1395–1400, tempera on poplar wood, 10-23/64 × 23-57/64. Staatliche Museum, Berlin, Inv. No. 1113. Photo Credit: bpk Bildagentur / Staatliche Museum / Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 3: Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, about 1370–1425), Nativity, about 1395–1400, tempera on poplar wood, 10-23/64 × 23-57/64. Staatliche Museum, Berlin, Inv. No. 1113. Photo Credit: bpk Bildagentur / Staatliche Museum / Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 4: School of Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, about 1370–1425), Nativity, 1390–1405, tempera on wood. Pinacoteca, Vatican Museums, Vatican State, Rome. Photo © Alinari Archives / Anderson / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 4: School of Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, about 1370–1425), Nativity, 1390–1405, tempera on wood. Pinacoteca, Vatican Museums, Vatican State, Rome. Photo © Alinari Archives / Anderson / Art Resource, NY.

These compositional design choices can be found in other Tuscan and Sienese paintings of the fifteenth century, such as

The Nativity and Annunciation to the Shepherds by Bicci di Lorenzo (1373–1452) in the Fogg Art Museum (fig. 5). What makes the Clowes panel more clearly tied to Lorenzo Monaco as a predecessor is evident in his later

Nativity paintings. In the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s

Nativity (about 1406–1410), Lorenzo Monaco included a pitched roof and cave enclosure, a recumbent Christ child, and the Holy Family (fig. 6). His

Nativity of 1414 (Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi) forms part of the predella of the

Coronation of the Virgin altarpiece (fig. 7). There, too, the artist included the same composition, as well as Joseph with his cap. What makes these versions notable—and indicate the Clowes panel is in the family of this school of artists—is the splendid array of gilding that now radiates from the baby Jesus and the angel in the sky.

Figure 5: Bicci di Lorenzo (Italian, 1373–1452), The Nativity and the Annunciation to the Shepherds, about 1440, tempera on panel, 12-1/16 × 29-1/2 in. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Berenson, 1920.19. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Figure 5: Bicci di Lorenzo (Italian, 1373–1452), The Nativity and the Annunciation to the Shepherds, about 1440, tempera on panel, 12-1/16 × 29-1/2 in. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Berenson, 1920.19. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Figure 6: Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, about 1370–1425), The Nativity, about 1406–1410, tempera on wood, gold ground, 8-3/4 × 12-1/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975, 1975.1.66.

Figure 6: Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, about 1370–1425), The Nativity, about 1406–1410, tempera on wood, gold ground, 8-3/4 × 12-1/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975, 1975.1.66.

Figure 7: Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, about 1370–1425), Nativity, Predella from the Coronation of the Virgin, 1414, tempera on wood, gold background, 177-11/64 × 137-51/64 in. Uffizi, Florence, Italy, Inv. 1890 no. 885. Photo Credit: Alfredo Dagli Orti / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 7: Lorenzo Monaco (Italian, about 1370–1425), Nativity, Predella from the Coronation of the Virgin, 1414, tempera on wood, gold background, 177-11/64 × 137-51/64 in. Uffizi, Florence, Italy, Inv. 1890 no. 885. Photo Credit: Alfredo Dagli Orti / Art Resource, NY.

While similar to these works by Lorenzo Monaco, the Clowes panel contains features that locate the work beyond his workshop. During the first half of the fifteenth century, artists were debating between the three-dimensional bodies and linear perspective of Masaccio (1401–1428) and the glistening surfaces of the International Gothic Style of Gentile da Fabriano (about 1370–1427).

In a now-famous 1940 essay, the art historian Roberto Longhi credits Fra Angelico with being the first artist to truly embrace and carry forward the accomplishments Masaccio had achieved in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence.

In two

Nativity paintings of the 1420s, Fra Angelico recreates many of the characteristic features of the previously discussed works but also includes a host of angels above the stable (Minneapolis Institute of Arts; Forlì, Pinacoteca Civica) (figs. 8 and 9).

Longhi credits Fra Angelico with mastering the solid bodies of Masaccio in these panels, particularly the Forlì

Nativity and its companion panel,

Agony in the Garden. In the Clowes panel, Joseph’s head hints at an awareness of Masaccio’s work in the Brancacci Chapel, and the shelter over Mary and Jesus—as in several of the aforementioned versions—uses an attempt at linear perspective to place a central focus on the veneration of the Christ child while allowing the space to recede into the background.

Figure 8: Fra Angelico (Italian, 1390–1455), The Nativity, about 1425, tempera on poplar panel, 11-1/8 × 6-1/2 in. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Bequest of Miss Tessie Jones in memory of Herschel V. Jones, 68.41.8.

Figure 8: Fra Angelico (Italian, 1390–1455), The Nativity, about 1425, tempera on poplar panel, 11-1/8 × 6-1/2 in. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Bequest of Miss Tessie Jones in memory of Herschel V. Jones, 68.41.8.

Figure 9: Fra Angelico (Italian, 1390–1455), The Nativity, about 1422–1448, tempera on wood, Pinacoteca Civica, Forlì, Italy, No. 59774. Photo Credit: Scala / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 9: Fra Angelico (Italian, 1390–1455), The Nativity, about 1422–1448, tempera on wood, Pinacoteca Civica, Forlì, Italy, No. 59774. Photo Credit: Scala / Art Resource, NY.

At the same time Fra Angelico and his followers would have seen the masterworks by Masaccio, they were also becoming acquainted with Gentile da Fabriano’s Strozzi Altarpiece, the

Adoration of the Magi (1423, Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi).

The artist of the Clowes panel was evidently inspired by the

Nativity predella panel in that altarpiece, which places the building, Holy Family, animals, and angel in a similar arrangement as in the Clowes Panel (fig. 10). The structure on the left shares the same L-shaped addition of both paintings. Furthermore, Gentile adds glittering stars and a crescent moon, repeated in a similar configuration in the Clowes panel. Given that the Clowes

Nativity contains extensive overpainting and

restoration attempts in the sky, the precise appearance of the original

sgraffito stars remains unknown. One might imagine that they were closer in shape and size to those of the Gentile panel. Regardless, this glistening, starlit sky and splendor radiating from the child and angel create a tactile luminescence for a narrative scene that would otherwise be absent from a Masaccio panel. As Fra Angelico’s career continued, his style incorporated more of Gentile’s surface decoration, which is evident in his 1440s frescoes in the Chapel of Nicholas V in the Vatican, as well as his

Last Judgment (1447–1448, Berlin, Staatliche Museum).

Figure 10: Gentile da Fabriano (Italian, 1385–1427), Predella with Nativity, from the Adoration of the Magi, the Strozzi Altarpiece, 1423, tempera on wood, 118-3/4 × 111-3/8 in. Uffizi, Florence, Italy, Inv. 1890 no. 8364. Photo Credit: Scala / Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 10: Gentile da Fabriano (Italian, 1385–1427), Predella with Nativity, from the Adoration of the Magi, the Strozzi Altarpiece, 1423, tempera on wood, 118-3/4 × 111-3/8 in. Uffizi, Florence, Italy, Inv. 1890 no. 8364. Photo Credit: Scala / Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY.

The Clowes Nativity shares several compositional details that place its origin within the school of Fra Angelico. While the overpaint obscures the original hues, the general colors are similar to those used by Fra Angelico and his followers in the 1420s and 1430s. The structures and figures indicate an artist in early fifteenth-century Tuscany, while the composition and golden accents clearly align with Gentile da Fabriano’s work on the Strozzi Altarpiece in Florence. Without further conservation intervention to remove the restorations, it is unlikely a specific artist will be named author of this piece. Unfortunately, evidence that the panel has been skinned, combined with the extent of overpainting, suggests that cleaning the panel may cause more harm than benefit.

As this was a predella panel, locating the other pieces of the larger altarpiece would likely add invaluable information regarding the origin and artist of the Clowes panel. There have been previous attempts to unite this painting with one of the unidentified works by Fra Angelico in the collection of Lorenzo de’Medici in the fifteenth century and then subsequently in the homes of families who worked for them, as described by Vasari. More information regarding the Clowes panel provenance prior to the nineteenth century is needed to confirm or deny these conjectures.

Author

Andrea Kibler Maxwell

Provenance

Possibly Hugo Kilényi (1840–1926), Budapest.

Ercole Canessa (1868–1929), New York, Paris and Rome;

Alfred F. Seligsberg (1869-1933), New York, by 1934;

Sale at (American Art Association, Anderson Galleries, New York) in 1934.

Probably purchased from this sale by (E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York);

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1934;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2014, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10001);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2014 (2014.89).

Exhibitions

Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA, 1934–1935, on loan;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 1, as Fra Angelico;

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 1;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, IN, 1962, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, no. 5.

References

Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), no. 1 (reproduced);

H.W. Janson, History of Art (New York: Abrams, 1962), 282, Ian Fraser notes the panel is similar to another by Gentile da Fabriano;

The Courier-Journal, The Louisville Times, “Old Masters' Favorite: Mother and Child,” 23 December 1962;

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 8, attributed to Fra Angelico;

John Pope-Hennessy, Fra Angelico (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974), fig. 82, as “imitator” of Fra Angelico;

Cover page photo by John H. Starkey, Star Magazine, Indianapolis, 23 December 1979.

Notes