Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

Authors

Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman

Provenance

Archduke Leopold Wilhelm (1614–1662), Brussels, then Vienna, by at least 1659;17

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Vienna, by 1895, and Staatsmuseum, Vienna, by 1923;18

In the Salzburg Residenz by 1933;

Purchased by I.G. Pollak in 1933.19

Lionello Venturi (1885–1961), Paris, by 1935;20

(Jacques Seligmann & Co., Paris, then New York) in 1935.21

(E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York);22

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, by 1940;23

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2014, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10073);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2014.

Exhibitions

Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH, 1940, Four Centuries of Venetian Painting, no. 56;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1954, Pontormo to Greco: The Age of Mannerism, no. 57;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 54;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1962, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, no. 21.

References

David Teniers the Younger, Theatrum Pictorium (Antwerp: Hendrick Aertssens, 1660);

Gustav K. Nagler, Neues allgemeines Künstler-Lexicon; oder Nachrichten von dem Leben und den Werken der Maler, Bildhauer, Baumeister, Kupferstecher etc., 22 vols. (Munich: E.A. Fleischmann, 1835–1852; reprint ed., Linz, 1904–1914), 7:155, no. 2;

Charles Le Blanc, Manuel de l’amateur d’estampes (Paris: Chez P. Jannet, 1856), 2:398, no. 9;

Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses (Vienna, 1882), no. 463;

Franz Wickhoff, “Les Écoles italiennes au Musée Impérial de Vienne,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 35 (1893): 140;

Führer durch die Gemälde-galerie. Alte-Meister. I. Italienische, Spanische, Französische Schulen (Vienna: Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses, 1895), no. 241;

J.B. Stoughton Holborn, Jacopo Robusti Called Tintoretto (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1903), 96;

Führer durch die Gemälde-galerie. Alte-Meister. I. Italienische, Spanische, Französische Schulen (Vienna: Kunsthistorishcen Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses, 1904), 77, no. 241;

Erich von der Bercken and August L. Mayer, Jacopo Tintoretto, 2 vols. (Munich: R. Piper & Co., 1923), 1:247;

Mary Pittaluga, Tintoretto (Bologna: N. Zanichelli, 1925), 142;

Four Centuries of Venetian Painting, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1940), cat. no. 56 (ill.);

Hans Tietze, Tintoretto (New York: Phaidon Press, 1948), 351;

Walter F. Friedländer, Pontormo to Greco: The Age of Mannerism, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1954), cat. no. 57;

John Maxon, “Two Notes on Tintoretto. II. A Sketch by Domenico Robusti il Tintoretto,” Bulletin of Rhode Island School of Design (December 1957), 2n11;

Bernard Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, Venetian School, 2 vols. (London: Phaidon Press, 1957), 1:173;

Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), cat. no. 54;

Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, exh. cat. (Bloomington: Indiana University Art Museum, 1962), no. 21;

Claire (Klara) Garas, “Le tableau du Tintoret du Musée de Budapest et le cycle peint pour l’empereur Rodophe II,” Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts 30 (1967): 44, fig. 34;

Klara Garas, “Das Schicksal der Sammlung des Erzherzogs Leopold Wilhelm,” Jahrbuch der Kunshistorischen Sammlungen in Wien 64 (1968): 224n357;

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 34;

Rodolfo Pallucchini and Paola Rossi, Tintoretto: Le opere sacre e profane, 2 vols. (Milan: Electa, 1982), 1:245, cat. A46; 2: fig. 671;

Paolo Ticozzi, Immagini dal Tintoretto: Stampe dal XVI al XIX secolo nelle collezioni del Gabinetto delle Stampe, exh. cat (Rome: Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica/Rome: De Luca, 1982), 40;

John Shearman, The Early Italian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983) 243;

Erasmus Weddigen, “Jacopo Tintoretto und die Musik,” Artibus et Historiae 10 (1984): 98, fig. 19;

Maria Agnese Chiari Moretto Wiel, Jacopo Tintoretto e i suoi incisori, exh. cat. (Venice: Palazzo Ducale/Milan: Electa, 1994), 50–52;

Lucy Whitaker and Martin Clayton, The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection: Renaissance and Baroque (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2007), 227, fig. 103;

Liana De Girolami Cheney, “Jacopo Tintoretto’s Female Concert: The Realm of Venus,” Journal of Literature and Art Studies 6, no. 5 (May 2016): 490–491, fig. 9.

Technical Notes and Condition

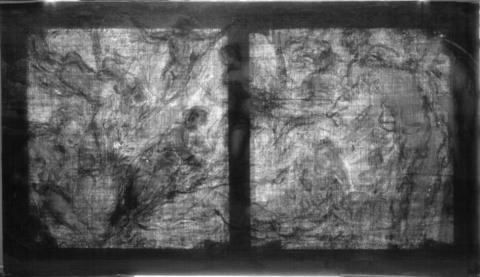

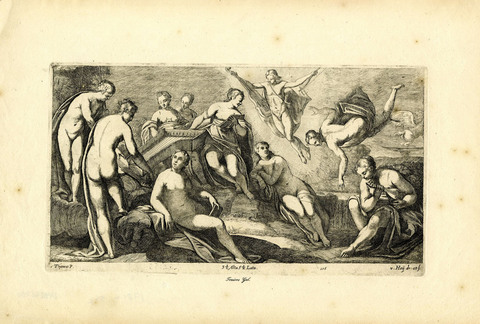

The support is a single piece of twill-weave canvas. The lack of the original tacking margins indicates that the picture has been cut down slightly, as visible by comparison to the engraving after David Teniers. The canvas has been relined.

The canvas was prepared with a gesso ground covered by a thick brown imprimatura layer.

Infrared reflectography shows prominent underdrawing executed in a fluid medium, probably oil paint. Notable adjustments to the composition include the elimination of the trees in the background, visible in the underdrawing but later painted out of the composition, and changes in the position of limbs and relative size of some of the Muses.

The paint is applied relatively thinly, with generally broad, loose brushwork and no areas of impasto. The color palette is limited, consisting primarily of earth pigments, pale skin tones, and blues in the figures' robes and sky. Ultramarine appears in the blue robes. A few bright red highlights are present on the figures' faces.

The picture shows evidence of several campaigns of varnish and retouching, but documentation of past treatment is lacking. Structurally, the painting is in stable condition, although suffering from discolored varnish, areas of abrasion, and retouchings that have become discolored and show pronounced textural differences.

Notes

-

On the iconography of Apollo and the Muses, see A.P. de Mirimonde, “Les concerts des muses chez les maîtres du nord,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 63 (1964): 129–158; H. Colin Slim, “Tintoretto’s ‘Music Making Women’ at Dresden,” Imago Musicae 4 (1987): 45–76; and Liana De Girolami Cheney, “Jacopo Tintoretto’s Female Concert: The Realm of Venus,” Journal of Literature and Art Studies 6, no. 5 (May 2016): 478–499. ↩︎

-

On Jacopo Tintoretto and his studio, see Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice, ed. Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, exh. cat. (Venice and Washington: Palazzo Ducale and National Gallery of Art/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018–2019), especially 28–35. On problems associated with the Tintoretto catalogue, see Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, “Toward a New Tintoretto Catalogue, with a Checklist of Revised Attributions and a New Chronology,” in Jacopo Tintoretto: Actas del Congreso Internacional “Jacopo Tintoretto” (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2009), 91–150. ↩︎

-

Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, “Toward a New Tintoretto Catalogue, with a Checklist of Revised Attributions and a New Chronology,” in Jacopo Tintoretto: Actas del Congreso Internacional “Jacopo Tintoretto” (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2009), 106–109. ↩︎

-

Lucy Whitaker and Martin Clayton, The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection: Renaissance and Baroque (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2007), 227–229. The picture measures 81-3/8 × 122 in. (206.7 × 309.8 cm) and currently hangs in Kensington Palace, London. See also Miguel Falomir, “Mythologies,” in Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice, ed. Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, exh. cat. (Venice and Washington: Palazzo Ducale and National Gallery of Art/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018–2019), 191–199, especially 196–198, and 258. ↩︎

-

In addition to the treatments of the theme mentioned in the principal text, other related pictures include Contest of the Muses and Pierides (Verona, Museo del Castelvecchio) and Concert of the Muses and Other Divinities (formerly Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, private collection), both on panel and probably originally decorating the inside top of a harpsicord or similar instrument, and a Concert of the Muses in a private collection in Rome. For these, the Amsterdam fragment, and the Dresden Six Female Musicians, see Rodolfo Pallucchini and Paola Rossi, Tintoretto: Le opere sacre e profane, 2 vols. (Milan: Electa, 1982), 1: cats. 102, 103, 190, 204, 382; 2: figs. 129, 130, 252, 268, 493. See also Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, “Toward a New Tintoretto Catalogue, with a Checklist of Revised Attributions and a New Chronology,” in Jacopo Tintoretto: Actas del Congreso Internacional “Jacopo Tintoretto” (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2009), 106–109 and checklist nos. F21, C47, C72, 215, 200. On the lost Dresden Apollo, the Muses, and the Three Graces, see Claire (Klara) Garas, “Le tableau du Tintoret du Musée de Budapest et le cycle peint pour l’empereur Rodophe II,” Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts 30 (1967): 29–48, fig. 34, and H. Colin Slim, “Tintoretto’s ‘Music Making Women’ at Dresden,” Imago Musicae 4 (1987): 45–76, fig. 9. On the Munich Contest of the Muses and the Pierides, see Erasmus Weddigen, “Jacopo Tintoretto und die Musik,” Artibus et Historiae 10 (1984): 67–119, fig. 10. In the opinion of the present authors, all the works considered in this note are by Tintoretto workshop assistants or followers. Some recent scholars, however, believe the Dresden Six Female Musicians and the Verona Contest of the Muses and Pierides to be autograph works by Jacopo Tintoretto. ↩︎

-

Carlo Ridolfi, Le maraviglie dell’arte, ed. Detlev Freiherr von Hadeln, 2 vols. (Berlin, 1914–1924), 2:50. Discussed by Claire (Klara) Garas, “Le tableau du Tintoret du Musée de Budapest et le cycle peint pour l’empereur Rodophe II,” Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts 30 (1967): 29–48; and H. Colin Slim, “Tintoretto’s ‘Music Making Women’ at Dresden,” Imago Musicae 4 (1987): 58–65. ↩︎

-

Maria Agnese Chiari Moretto Wiel, Jacopo Tintoretto e i suoi incisori, exh. cat. (Venice: Palazzo Ducale, 1994), cat. no. 34, 50–52. How this painting came to be Leopold Wilhelm’s collection is unknown; the small size suggests that it might have been added to top off a larger consignment of pictures from Venice, such as the outstanding works of Giorgione, Titian, and Antonello da Messina from Venetian collector Bartolomeo dalla Nave (or della Nave, about 1571–1632) that were sold to the Marquess of Hamilton and then to Leopold Wilhelm about 1650; these pictures still form the core of the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s Venetian holdings. For Dalla Nave and his collection, see Simone Furtlehner and Rosella Lauber in Il collezionismo d’arte a Venezia: Il Seicento, ed. Linda Borean and Stefania Mason (Venice: Marsilio, 2007), 258–261. ↩︎

-

For all of the published attributions, see References. The Venturi and Suida manuscript opinions are in files at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Rodolfo Pallucchini and Paola Rossi, Tintoretto: Le opere sacre e profane, 2 vols. (Milan: Electa, 1982), 1: cats. 199, A93; 2: figs. 257, 716. ↩︎

-

For this category of independent picture pioneered in sixteenth-century Venice, see Monika Schmitter, “The Quadro da Portego in Sixteenth-Century Venetian Art,” Renaissance Quarterly, 64, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 693–751. ↩︎

-

E.g., Erasmus Weddigen, “Jacopo Tintoretto und die Musik,” Artibus et Historiae 10 (1984): 98, referring to the Indianapolis picture as an “abozzo,” or sketch. ↩︎

-

Roland Krischel, “Tintoretto at Work,” in Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice, exh. cat. (Venice and Washington: Palazzo Ducale and National Gallery of Art/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018–2019), 54. Examples of patrons for whom compositional sketches by Tintoretto have survived are Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga of Mantua and, on several occasions, government officials of the Venetian Republic. ↩︎

-

Carlo Ridolfi, Le maraviglie dell’arte, ed. Detlev Freiherr von Hadeln, 2 vols. (Berlin, 1914–1924), 2:54. The reference was pointed out by Tietze in Four Centuries of Venetian Painting, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1940), cat. no. 56. ↩︎

-

The best comparisons to works from the Tintoretto studio that have been associated with Domenico are in several pictures from the undated cycle on the life of Saint Catherine of Alexandria executed for the convent of Santa Caterina: The Scourging of Saint Catherine, Saint Catherine in Prison, and Saint Catherine Martyred on the Wheel. Rodolfo Pallucchini and Paola Rossi, Tintoretto: Le opere sacre e profane, 2 vols. (Milan: Electa, 1982), 1: cats. 428, 429, 430; 2: figs. 545, 546, and 548; Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, “Toward a New Tintoretto Catalogue, with a Checklist of Revised Attributions and a New Chronology,” in Jacopo Tintoretto: Actas del Congreso Internacional “Jacopo Tintoretto” (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2009), checklist nos. 276, 275, 273. These are not universally identified as by Domenico, however; see Giovanna Nepi Sciré, “Nos. 29–34, Il Ciclo di Santa Caterina,” in Tintoretto: Il Ciclo di Santa Caterina e la quadreria del Palazzo Patriarcale, exh. cat. (Venice: Museo Diocesano/Milan: Skira, 2005). The cycle of paintings celebrating the history of the Gonzaga family (Munich, Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen), firmly documented to 1578–1580, is considered to be largely by Domenico, working from his father’s figure drawings. There are general similarities to the Indianapolis painting in the few female (but not nude) figures, e.g., The Entry of the Infante Philip into Mantua. Rodolfo Pallucchini and Paola Rossi, Tintoretto: Le opere sacre e profane, 2 vols. (Milan: Electa, 1982), 1: cat. 399; 2: fig. 511; Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman, “Toward a New Tintoretto Catalogue, with a Checklist of Revised Attributions and a New Chronology,” in Jacopo Tintoretto: Actas del Congreso Internacional “Jacopo Tintoretto” (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2009), checklist no. 243; and Cornelia Syre, ed., Tintoretto: Der Gonzaga-Zyklus, exh. cat. (Munich: Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen/Munich: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2000), 108–118, cat. no. 8. ↩︎

-

British Museum, no. 1907.0717.9. Hans Tietze and Erika Tietze-Conrat, The Drawings of the Venetian Painters in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (New York, 1944; reprint ed., New York: Hacker Art Books, 1979), 264, no. 1526/9. Another comparison is a drawing showing a different version of the Concert of the Muses: Hans Tietze and Erika Tietze-Conrat, The Drawings of the Venetian Painters in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (New York, 1944; reprint ed. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1979), 260, no. 1472, plate CXVII (Amsterdam, Nicholas Beets Collection). For recent perspectives on Domenico’s drawing style, see John Marciari, Drawing in Tintoretto’s Venice, exh. cat (New York: Morgan Library and Museum and National Gallery of Art/London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2018–2019), 143–165; Gabriele Matino, “Domenico Tintoretto’s Life Drawing: Anatomy of Artistic Reform,” in Gabriele Matino and Cynthia Klestinec, eds., Art, Faith and Medicine in Tintoretto’s Venice, exh. cat. (Venice: Scuola Grande di San Marco/Venice: Marsilio and Save Venice, Inc., 2018–2019), 85–93; and Michiaki Koshikawa, “Jacopo and Domenico Tintoretto as Draftsmen: Some Debatable Works from circa 1580–1600,” Aspects of Problems in Western Art History 17 (2019): 135–142. ↩︎

-

The painting is listed as no. 357 in a 1659 handwritten inventory, transcribed and published in 1883; see Adolf Berger, “Inventar der Kunstsammlung des Erzherzogs Leopold Wilhelm von Ősterreich, nach der Originalhandschrift im Fürstlich Schwarzenberg’schen Centralarchive,” in Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses 1, part 2 (1883), cvi. It is also included as an unnumbered engraving by Nicolaus van Hoy in David Teniers the Younger’s Theatrum Pictorium (Antwerp: Hendrick Aertssen, 1660), which documents Habsburg Archduke Leopold Wilhelm’s most admired Italian paintings; the engraving is also included as plate 106 in a second edition of this publication (Antwerp: Jacob Peeters, 1684). ↩︎

-

The painting is included in Führer durch die Gemälde-Galerie, Alte Meister. I., Italienische, Spanische und Französische Schulen (Vienna: Kunsthistorische Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses, 1895), no. 241 as Jacopo Tintoretto, and this number is written on the stretcher’s crossbar. The painting is subsequently listed as in the Staatsmuseum, Vienna, in Erich von der Bercken and August L. Mayer, Tintoretto (Munich: R. Piper & Co. 1923), 1, 247. ↩︎

-

Francesca Del Torre, curator, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, email message to Annette Schlagenhauff, 10 October 2014, which states that this painting served as a decorative picture in the Residenz Salzburg until its sale on 1 February 1933 to “Commendatore J.(sic) G. Pollak.” This is likely a reference to Ignaz (Ignace) George Pollak, diplomatic envoy of San Marino to Germany and Austria, about whom little is known. ↩︎

-

Venturi is identified as the owner on Invoice of Merchandise, 24 September 1935, Box 299, Folder 9 (Invoices 1935), Jacques Seligmann & Co. Records, Archives of American Art. Here it states that “Apollon et les muses” was received from Prof. L. Venturi on consignment on 11 July 1935, and will be sent to Werner Jucker in New York, via Le Havre, in September 1935. Jucker likely worked with the Seligmann family as a receiving agent in New York. Venturi also issued an expertise on this painting, wherein he stated, “Ce tableau a été assigné à la galerie du Château de Salzburg où il est resté jusqu’en 1933, lorsqu’il a été vendu,” which corroborates information received in 2014 from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna; see Lionello Venturi, 1 September 1937, File C10073 (2014.82), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

This painting is also listed, as stock number 14.203, in the Stock Catalogues of Seligmann’s Paris office, see Box 288, Folder 8 (Stock Catalogs, Paris office), Jacques Seligmann & Co. Records, Archives of American Art. With thanks to Victoria Reed, Sadler Curator for Provenance, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for providing this reference. ↩︎

-

Silberman’s possession of this painting is documented in the Frick Art Reference Library Photoarchive Records, see Bib Record Number b1492909 in Frick Digital Collections. Here it states that a verbal communication on 11 April 1939 from Dr. E. Tietze-Conrat notes that the painting was currently with the E. and A. Silberman Gallery. Many years later, and likely in error but repeated by others, Silberman recalled that the painting was formerly in the collection of the Princess Thurn and Taxis; see Letter from Allen W. Clowes to David Carter, 28 May 1959, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

The painting was first exhibited in the United States under Clowes’s ownership in 1940; see Hans Tietze, Four Centuries of Venetian Painting, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1940), no. 56. ↩︎