Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

Pronounced horizonal ridges along joins in panels at approximately one-third and two-thirds up the composition. Partial/damaged inscription on left shoulder of the figure on the right (St. Amador): S AMAD[O]R. Vertical burn above and to the right of St. Amador’s head. (2014.83.1)

Horizonal ridges along joins in panels at approximately one-third and two-thirds up the composition (2014.83.2)

Entry

Author

Provenance

From the predella (banco) of an altarpiece, likely commissioned for the church of San Miguel or church of San Vicente in Cardona (Barcelona) and dismantled in the late 1800s or early 1900s.

James W. Barney (1878–1948), New York;9

Collection of Ricardo Viñas, Barcelona by at least 1952.10

(Newhouse Galleries, New York) by 1957;11

Edith Whitehill Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1959;12

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1959–2014, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10078A-B);

Given to Indianapolis Museum of Art, now Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2014.

Exhibitions

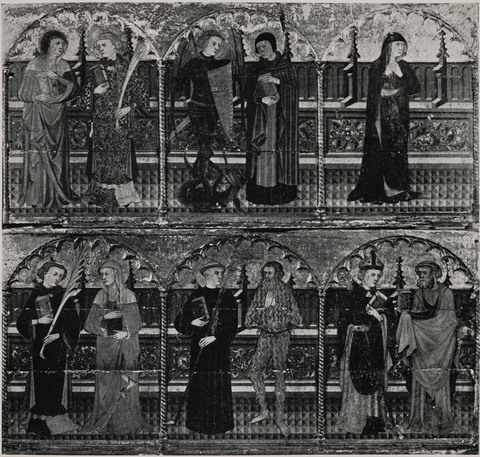

Salón de Tinell y Real Capilla de Santa Águeda, Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, Barcelona, 1952, Exposición de Primitivos Mediterráneos, nos. 162 and 163, as Maestro del Pentecostés de Cardona, Dos fragmentos de una misma predela. Tres santos, San Miguel y la Virgen (no. 162). En el otro: San Esteban, Maria Magdalena, San Benito, San Onofre, un santo obispo y San Pedro (Two framents of the same predella. Three saints, Saint Michael and the Virgin (no. 162). In the other: Saint Stephen, Mary Magdalene, Saint Benedict, Saint Onuphrius, a bishop saint and Saint Peter), Colección Ricardo Viñas, Barcelona;

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, IN, 1960, Indiana Collects, nos. 10 and 11;

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, IN, 1962, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Fund Collection, nos. 25a and 25b;

References

Chandler Rathfon Post, A History of Spanish Painting, vol. 10 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950), 298–299, fig. 112 (reproduced);

Exposición de Primitivos Mediterráneos (Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 1952), 62–63, nos. 162 and 163;

Advertisement for Newhouse Galleries, The Connoisseur 140, no. 566 (January 1958): lxvi, (reproduced 2014.83.2 only);

Archivo Español de Arte 31 (1958): 165, no. 36, ill. (reproduction of second panel);

Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection (Bloomington: Indiana University Art Museum, 1962), nos. 25a and 25b;

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 48–49;

Josep Gudiol Ricart and Santiago Alcolea Blanch, Pintura gótica catalana (Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, 1986), 99, no. 271, figs. 473 and 473 (reproduced);

Sotheby’s New York, Thursday, 28 January 1999, Property of a Charitable Organization, Pere Vall (Master of the Cardona Pentacost), active 1400–1425, The Madonna Dolorosa and Saints Anne and Lawrence: A Pair of Panels from a Retable, both tempera on panel [lot 00426], mentions IMA’s panels in write up for sale of two other panels from the same predella.

Ana Orriols i Alsina, “La pintura gòtica a Sant Miquel de Cardona,” in L’església parroquial de San Miquel de Cardona: El gòtic al mig Cardener, ed. Mercedes Juan i Verdejo et al. (Manresa: Centre d’Etudis del Bages, 2003), 131–193, esp. 176–178, figs. 25c and 25f, as private collection, USA (reproduced);

Anna Orriols, “Vall, Pere,” Magistri Cataloniae, accessed 20 December 2019, http://www.magistricataloniae.org/en/indexmceng/codumentedart/item/vall-pere.html, as “seis compartamentos de la predela de un retablo (EEUU, col. part.).”

Mark A. Roglán, ed., Meadows Museum: A Handbook of the Collection (Dallas: Scala Arts in association with Meadows Museum, 2021).

Notes

-

The most extensive outline of Pere Vall’s life is in Ana Orriols i Alsina, “La pintura gòtica a Sant Miquel de Cardona,” in L’església parroquial de San Miquel de Cardona: El gòtic al mig Cardener, ed. Mercedes Juan i Verdejo et al. (Manresa: Centre d’Etudis del Bages, 2003), 131–193. ↩︎

-

Chandler Rathfon Post referred to the works now attributed to Pere Vall, whom he called The Master of the Cardona Pentecost, in his monumental A History of Spanish Painting, beginning in the second volume, published in 1930. It was not until the appendix of the tenth volume that he associated the predella of the Indianapolis panels with the artist. See Post, A History of Spanish Painting, vol. 2 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930), 282–88, and vol. 10 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950), 298–299, fig. 112, where he cites previous mentions of the The Master of the Cardona Pentecost. See also Ana Orriols i Alsina, “La pintura gòtica a Sant Miquel de Cardona,” in L’església parroquial de San Miquel de Cardona: El gòtic al mig Cardener, ed. Mercedes Juan i Verdejo et al. (Manresa: Centre d’Etudis del Bages, 2003), 136–137, nn.19–21. ↩︎

-

Judith Berg Sobre, Behind the Altar Table: The Development of the Painted Retable in Spain, 1350–1500 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1989), especially 184–195. ↩︎

-

Ana Orriols i Alsina, “La pintura gòtica a Sant Miquel de Cardona,” in L’església parroquial de San Miquel de Cardona: El gòtic al mig Cardener, ed. Mercedes Juan i Verdejo et al. (Manresa: Centre d’Etudis del Bages, 2003), 138–140. ↩︎

-

The total potential number of panels in the predella was suggested by both Post and Orriols i Alsina based on the six panels (in two groups of three) that were still intact in the 1950s (see below) in addition to the content of the panels, which include one image of a single saint, probably Mary (a Mater Dolorosa) and the likely existence of a tabernacle in the center of the predella as was typical in late medieval Catalan retables. Chandler Rathfon Post, A History of Spanish Painting, vol. 10 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950), 298. Judith Berg Sobre, Behind the Altar Table: The Development of the Painted Retable in Spain, 1350–1500 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1989). Ana Orriols i Alsina, “La pintura gòtica a Sant Miquel de Cardona,” in L’església parroquial de San Miquel de Cardona: El gòtic al mig Cardener, ed. Mercedes Juan i Verdejo et al. (Manresa: Centre d’Etudis del Bages, 2003), 176–178. For proposed reconstructions of some of the other altarpieces from the church of Sant Miquel in Cardona, see ibid., appendices 2 and 3, 183–184. ↩︎

-

Andreu Galera i Pedrosa records the sponsorship of 29 chapels in the church of St. Miquel in Cardona between 1300 and 1556. See Andreu Galera i Pedrosa “L’Església dels prohoms. La fundació de beneficis eclesiàstics eimples a Sant Miquel de Cardona (Segles XIII–XVI),” in L’església parroquial de San Miquel de Cardona: El gòtic al mig Cardener, ed. Mercedes Juan i Verdejo et al. (Manresa: Centre d’Etudis del Bages, 2003), 119–120. ↩︎

-

Ana Orriols i Alsina, “La pintura gòtica a Sant Miquel de Cardona,” in L’església parroquial de San Miquel de Cardona: El gòtic al mig Cardener, ed. Mercedes Juan i Verdejo et al. (Manresa: Centre d’Etudis del Bages, 2003), 176–178. Note that Orriols i Alsina lists all six panels as in a private U.S. collection. The suggestion that the panels come from the church of Sant Miquel in Cardona was picked up by María Cruz de Carlos in an unpublished text in curatorial files of the Indianapolis Museum of Art. All authors, including the present one, note that it is impossible at this time to prove the exact origin of the altarpiece but agree that Sant Miquel is certainly likely owing to the fact that each of the saints represented were known to have been venerated at that church. For a list of chapel dedications at Sant Miquel de Cardona and their locations within the church, see Andreu Galera i Pedrosa “L’Església dels prohoms. La fundació de beneficis eclesiàstics eimples a Sant Miquel de Cardona (Segles XIII–XVI),” in L’església parroquial de San Miquel de Cardona: El gòtic al mig Cardener, ed. Mercedes Juan i Verdejo et al. (Manresa: Centre d’Etudis del Bages, 2003), 119–120. ↩︎

-

Unpublished study by María Cruz de Carlos, File C10078, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. For the life of Saint Amador and his iconography in context, see Paulino Rodríquez Barral, La justicia del más allá: Iconografía en la Corona de Aragón en la baja Edad Media (Valencia: Universitat de València, 2007), 195–197. ↩︎

-

See Chandler Rathfon Post, A History of Spanish Painting, vol. 10 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950), 298. ↩︎

-

See Exposición de Primitivos Mediterráneos (Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 1952), 62–63, nos. 162–163. ↩︎

-

It seems to be at this point that the panels of the banco were further broken up for sale. See advertisement, The Connoisseur 140, no. 566 (January 1958), lxvi (C10078B is reproduced). ↩︎

-

Purchase agreement, 10 April 1959, File C10078A-B, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎