Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

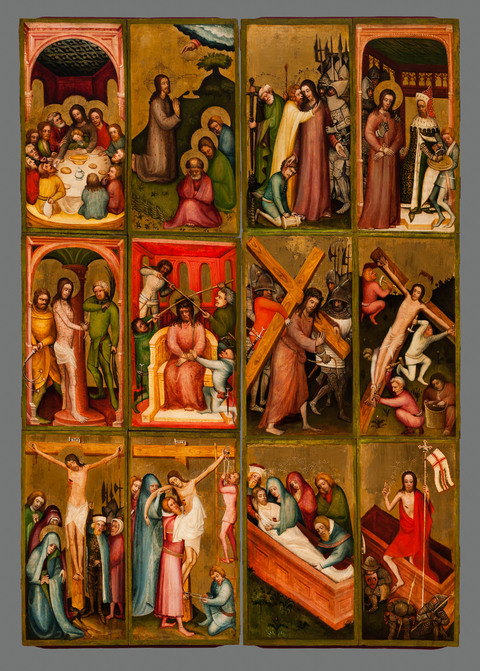

This group of twelve brightly painted and gilded panels depicts scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Last Supper, Agony in the Garden, Kiss of Judas, Pilate Washing His Hands, Christ at the Column, The Mocking of Christ, Christ Carrying the Cross, Christ Nailed to the Cross, Crucifixion, Descent from the Cross, Entombment, and Resurrection.

These relatively unknown panels have been reproduced only rarely.

Passion of Christ entered the Clowes Collection by purchase from the Newhouse Galleries, New York, in three installments from November 1951 to April 1952. The panels were acquired as “Austrian primitives,” because they were said to have come from a convent near Bregenz, in present-day Austria.

In consultation with Newhouse Galleries, a neo-Gothic style frame was constructed for the slightly irregular-sized individual panels, which were arranged as a triptych for display at Westerley, the Indianapolis estate of Dr. and Mrs. Clowes (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Unknown artist (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, arranged as a triptych prior to 2007. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 1: Unknown artist (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, arranged as a triptych prior to 2007. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

A few years later, Karel G. Boon and Kurt Bausch were consulted regarding the Passion panels and were sent photographs of the triptych arrangement,

but neither provided more than a stylistic assessment based on their possible place of creation. The disposition of the panels was addressed in 1980, when they were published by Anthony Janson and A. Ian Fraser, with research assistance by Georgina Spicer. The scholars speculated that the twelve panels were part of an original group of eighteen, the other six presumed to have gone missing. Such a complete cycle, they suggested, would have depicted the entire Life of Christ beginning with the Annunciation and continuing through his Entry into Jerusalem.

This premise was supported by similar altarpieces produced in the Lower Rhine region and Cologne at the end of the Middle Ages, such as one from Roermond near Amsterdam, today in the Rijksmuseum (fig. 2).

Yet, the Clowes

Passion of Christ panels raise a number of questions, beginning with their correct disposition and arrangement. While this question can now be answered after a renewed, thorough visual examination—the results of which will be presented here—speculation as to their place of origin and date of creation remains and will be summarized below.

Figure 2: Unknown artist, Eighteen Scenes from the Life of Christ, known as the Roermond Passion, about 1435, oil on canvas on panel, 43-11/32 × 68-15/64 in. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-1491.

Figure 2: Unknown artist, Eighteen Scenes from the Life of Christ, known as the Roermond Passion, about 1435, oil on canvas on panel, 43-11/32 × 68-15/64 in. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-1491.

Technical study of the panels was conducted at the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2006–2007, when the panels were removed from their frames. At this time, the individual panels, previously presumed to be of identical dimensions, were determined to be of slightly different sizes: Christ at the Column and The Mocking of Christ are almost an inch (2–2.6 cm) shorter than the neighboring panel, Pilate Washing His Hands. These differences in height, which were visually minimized by the neo-Gothic-style frame, are key to determining the original arrangement of the ensemble.

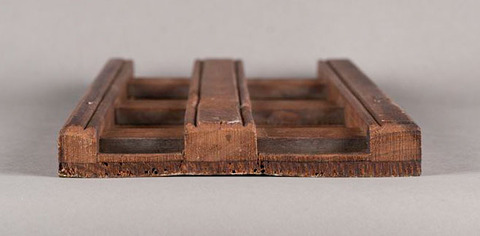

The study brought other considerations to light. The

cradle consists of three vertical wooden bars and sliding horizontal members, probably added to the fir support in the early twentieth century, and some edges of the bars are

beveled (fig. 3). In addition,

The Last Supper,

Agony in the Garden, Kiss of Judas, and

Pilate Washing His Hands each have a strip of wood attached to the top of the panel, whereas the

Crucifixion,

Descent from the Cross,

Entombment, and

Resurrection panels have a similar strip glued to the bottom. These strips were likely added to strengthen the wooden support probably after it had been thinned but before being cut into twelve narrative scenes. Finally, on the front, each scene is delimited by a border of green paint. When the panels were assembled in a triptych format, the differing widths of the panels was obscured.

Figure 3: Edges of cradle on Pilate Washing His Hands (panel D). Unknown artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 3: Edges of cradle on Pilate Washing His Hands (panel D). Unknown artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

These structural and physical observations, when taken together, allow for a probable reconstruction of the original arrangement of the ensemble. The Passion scenes could only have been arranged in three horizontal rows separated onto two large panels that served as the wings of an altarpiece. In this orientation, the scenes would have been read from left to right. The Passion cycle begins with

The Last Supper and

Agony in the Garden at the top of the left wing and continues with

Kiss of Judas and

Pilate Washing His Hands on the right wing. The second row shows

Christ at the Column and

The Mocking of Christ on the left wing and

Christ Carrying the Cross and

Christ Nailed to the Cross on the right wing. The bottom row concludes the Passion cycle with

Crucifixion and

Descent from the Cross on the left wing and

Entombment and

Resurrection on the right wing. Only in this configuration of two wings can the observations mentioned above be adequately reconciled. Moreover, this arrangement also accounts for the variations in height between the scenes; note, for example, the differences in height between

Agony in the Garden and

Kiss of Judas on the top row, and

Descent from the Cross and

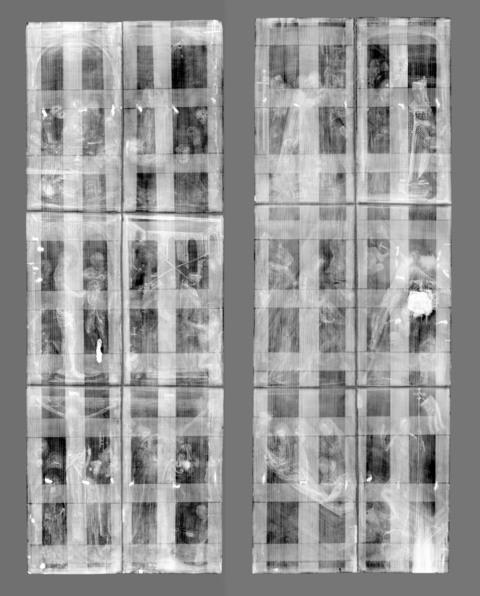

Entombment on the bottom row (fig. 4). This configuration also resolves the issue of the anomalous edges of the stretcher bars; all the beveled edges are exterior edges of one of the two panels (fig. 5). Two campaigns of numbering appear on the panels' backs, which now gain significance. The first took place around the time the panels were sawn apart: panels A, B, E, F, J and I show Roman numerals (I–VI) in blue near the top of each panel; panels C, D, H, G, L, K show Arabic numerals (1–6) in off-white near the top of each panel. The second campaign dates from when the panels were reframed in a novel configuration shortly after Clowes acquired them, and these show Arabic numbers in red, though only partially extant today. The proposed reconfiguration of the twelve panels as two equal-sized wings is corroborated by an X-ray image (fig. 6), which shows the continuation of woodgrain along each wing.

Figure 4: Panel height differences between rows on right and left altarpiece wings. Unknown artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 4: Panel height differences between rows on right and left altarpiece wings. Unknown artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 5: Continuous cradle structure on back. Unknown artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 5: Continuous cradle structure on back. Unknown artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 6: X-radiograph. Unknown Artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 6: X-radiograph. Unknown Artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

This reconfiguration also shows how the twelve panels integrate into the whole composition. An overall unity is achieved, as can be seen in select examples: the proximity of the group of soldiers in Kiss of Judas and Pilate Washing His Hands, the complementary placement of the crosses throughout, and the repetitive positioning of the sarcophagi in both final scenes of the cycle. An integrated, and overall, compositional structure also becomes apparent when surveying the three rows of scenes: the top row depicts Christ’s farewell and his subsequent interrogation, the middle row centers on his suffering, and the bottom row focuses on the crucifixion and mourning with an emphasis on the grieving figure of Mary (compassio Mariae) at bottom left.

The panels' place of origin has also been a matter of great speculation among scholars. G.H.A. Clowes’s correspondence with Newhouse Galleries at the time of acquisition, where they are referred to as “Austrian primitives,” derived, at least in part, from provenance information furnished by Clyde and Bertram Newhouse that indicated the panels came from a convent near Bregenz. In a 1980 essay documenting the holdings of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Janson and Fraser published them as “German School.” They saw parallels in the works of Master Bertram and Konrad von Soest, as well as to Bohemian paintings of the period. Although they noted a close stylistic affinity between the panels and an altarpiece from Schloss Tirol (fig. 7) painted by an Austrian master in about 1370–1372, they believed that an alternate Bavarian origin was also possible.

Janson and Fraser would have been aware of German Medievalist Alfred Stange’s correspondence with The Clowes Fund, in which he had linked the panels stylistically to ones from other altars depicting the Passion of Christ, such as the six now in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich that were probably created in the region near Bregenz.

Stange noted that a definite place of origin would remain elusive, but he speculated that the Clowes panels might have been made in Bregenz, Lindau, or St. Gallen, towns along the southern edge of Lake Constance.

Boon proposed Westphalian origins, while Bausch again proposed a south German, or Austrian, origin. Fritz Grossman proposed a Styrian painter, and Charles S. Kuhn, with whom Mark Roskill was in contact, suggested Westphalian origins.

Figure 7: Unknown artist (Austrian), Adoration of the Magi (detail from the Altar of Schloss Tirol), about 1370–1372. Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Ältere kunstgeschichtliche Sammlung, Inv.Nr. Gem 1962 (loan of the Prämonstratenser Chorherren-Stift Wilten). Photo: Tiroler Landesmuseen.

Figure 7: Unknown artist (Austrian), Adoration of the Magi (detail from the Altar of Schloss Tirol), about 1370–1372. Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Ältere kunstgeschichtliche Sammlung, Inv.Nr. Gem 1962 (loan of the Prämonstratenser Chorherren-Stift Wilten). Photo: Tiroler Landesmuseen.

The variety of opinions voiced by these art historians indicates how difficult it is to ascribe the Clowes Passion cycle to a particular region. The painter of these panels, however, was clearly under Bohemian influence, regardless of where they were made. The influence is apparent in the painter’s approach to narrative, the rendering of volume in the figures, with their strongly graded shading from dark to light, as well as the lively, puffy qualities of the drapery. The cycle is reminiscent of works by Master Theodoric, from the mid-thirteenth century, or Master Bertram, who worked under the former’s influence. Yet, the individual compositions as well as much of the iconography show a similarity to Passion scenes from regions farther to the northwest, for example, the altar in the parish church at Kirchsahr, dating to the first quarter of the fifteenth century, or the renowned “Golden Panel,” dating to about 1420, now at the Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum in Hanover. In the “Golden Panel,” the individual compositions, the spatial treatment of the scenes, and the postures and handling of the figures are similar to those in the Clowes Passion of Christ. However, to this author, a stylistic similarity is less certain between the Clowes Passion of Christ and the panels now in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, referenced by Stange and mentioned above.

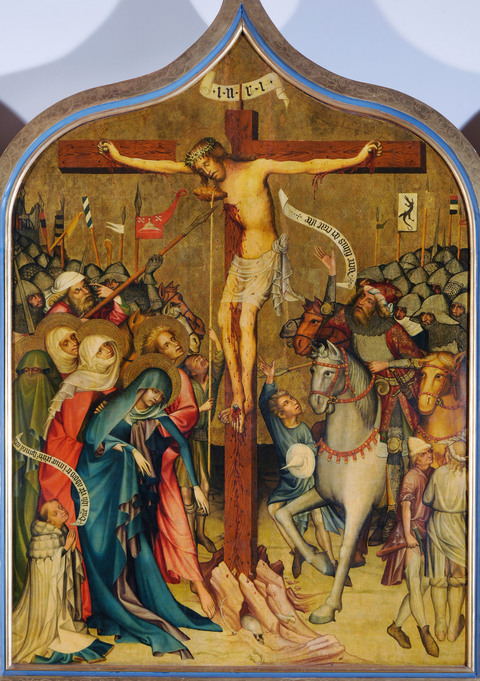

Certain features seem to point to a more southern origin for the Clowes cycle, and although the information that it hailed from a convent near Bregenz is vague, it cannot be completely disregarded. The rather soft painting style, as well as the almost caricature-like facial expressions that demonstrate a particular interest in depicting strong emotions, suggest an origin in the south, or southeast, most likely in the Austrian realm. A southern origin is further suggested by the form of the haloes, which are composed of several radially emanating grooves, as well as by the emphatic finger-pointing gesture made by the captain standing among the soldiers and mourners (fig. 8). For the Crucifixion scene, several Styrian, or Bavarian, examples foreground a Bohemian influence, such as the spectacular Calvary altarpiece of about 1427 by Thomas de Coloswar (Tamás Kolozsvári), now at the Christian Museum (Keresztény Múzeum) at Esztergom (fig. 9).

And finally, the wood type—fir—also suggests a more southern origin. Janson and Fraser had previously noted this affinity to the Altar of Schloss Tirol (see fig. 7), which would have been inconceivable without the influence of the court culture of Bohemia. Yet, its author would not have been close to the court artists at Prague, but rather to the provincial style of Master Theodoric. Several features of the

Passion of Christ do, in fact, link closely to the Altar of Schloss Tirol, namely, the summary treatment of the garments and the differences in scale among the almost doll-like figures. Further similarities can be seen in the modeling of the figures' heads, in addition to the frequent appearance of rounded faces with heavy eyelids. The color palette is also comparable, with its preference for deep red, light blue, and olive green. That altar dates to about 1370–1372, so, based on the more elongated figures in the

Passion of Christ and a comparison of both the Agony in the Garden, and the Resurrection scenes, a slightly later date is indicated for the Clowes work. This is further suggested by the tendency to enclose the scenes in complex architectural settings that create ornamented niches for the figures. Several iconographic details also point to a later date, specifically the devotional qualities of representations of Christ Carrying the Cross that appear after 1400 and highlight the figures of Christ and Simon of Cyrene, or the depiction of the cross with an elongated vertical element, which becomes prevalent at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Details of the armor and armaments also seem to conform to this time period; the epitaph for Ulrich Reichenecker, made by a Styrian painter in about 1410 (Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz), is one example (fig.10).

These factors all lead to a creation date of about 1415–1420 for this

Passion of Christ cycle.

Figure 8: Crucifixion (Panel I). Unknown Artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 8: Crucifixion (Panel I). Unknown Artist, (South German or Austrian?), Passion of Christ, about 1415–1420, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2004.157A-L.

Figure 9: Thomas de Coloswar (Hungarian, active 1427), Calvary Altar from Garamszentbenedek, 1427, gilded tempera on wood, 95-9/32 × 69-11/16 in. Keresztény Múzeum, Esztergom, Hungary, Inv. 54.3. Photograph by Attila Mudrák.

Figure 9: Thomas de Coloswar (Hungarian, active 1427), Calvary Altar from Garamszentbenedek, 1427, gilded tempera on wood, 95-9/32 × 69-11/16 in. Keresztény Múzeum, Esztergom, Hungary, Inv. 54.3. Photograph by Attila Mudrák.

Figure 10: Styrian painter, Epitaph for Ulrich Reichenecker, about 1410, tempera on wood, 55-3/4 × 63-5/8 in. Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz, Inv. No. 303. Photo: UMJ/N. Lackner.

Figure 10: Styrian painter, Epitaph for Ulrich Reichenecker, about 1410, tempera on wood, 55-3/4 × 63-5/8 in. Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz, Inv. No. 303. Photo: UMJ/N. Lackner.

The proposed reconfiguration of the Passion of Christ panels raises the question of their placement within a church altarpiece, a retable. Due to the heavy use of gilding in several painted scenes, the wings were unlikely to have been exterior panels. Because the Passion of Christ is a finite story, and because the orientation of the individual scenes has now been determined through examination, it no longer seems plausible that they were part of a larger cycle, configured in a different way. However, a third option presents itself: that they were side-wings of a moveable triptych and flanked a yet-to-be identified central image. In such a configuration, the central panel could have depicted a pietà or a lamentation group, the latter of which would make a logical bridge between the adjacent scenes on the bottom row between Descent from the Cross and Entombment. The central scene may also have been a three-dimensional, carved Crucifixion with three crosses.

Such a hypothetical altar, when open, would span 150 to 160 cm, which, due to its scale, might more easily be envisaged as a side, rather than a main, altar in a church or chapel. This cycle, which demonstrates a focus on the salvation story by bringing the suffering of Christ to its viewers, was clearly intended to evoke a feeling of compassion. Whether or not this altarpiece was located in a convent or church in the vicinity of Bregenz, these interesting side wings of a late Gothic altar add to our scarce knowledge about painting in the Austrian region near Lake Constance.

Author

Ágota Varga, translated by Christine Seidel and Annette Schlagenhauff

Provenance

Convent near Bregenz, present-day Austria.

Private Collection, Austria or Germany;

Newhouse Galleries, New York, by 1951–1952;

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1951–1952;

The Clowes Fund, from 1958–2004, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10002).

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2004.

Exhibitions

John Herron Art Museum, Indianapolis, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, 1959, no. 2 as Passion of Our Lord;

University of Notre Dame, The Art Gallery, Notre Dame, A Lenten Exhibition,1962, no. 2.

References

“Fourteenth Century Easter Story,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, 21 April 1957, 38–39;

Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: John Herron Art Museum, 1959), no. 2;

A Lenten Exhibition, exh. cat. (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, The Art Gallery, 1962), no. 2;

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), xlvi, 172–173;

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, Indianapolis Museum of Art Collections Handbook (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1988), 48–49;

Ágota Varga, “Zwölf wenig bekannte Passionstafeln vom Anfang des 15. Jahrhunderts. Ein Vorschlag zur Rekonstruktion der Bildreihe in der Sammlung des Indianapolis Museum of Art,” Aachener Kunstblätter 65 (2014), 45–55.

Notes