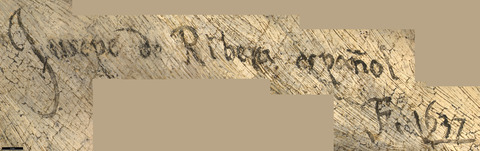

Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

Signed and dated lower left, on paper below figure’s proper left hand: Jusepe de Ribera español / F. 1637

Entry

In the 1630s, Jusepe de Ribera developed a hybrid genre of painting imaginary portraits of ancient philosophers: single male figures dressed in tattered clothes and engaged with books or instruments of learning. According to the intellectual historian Charles Salas, the artist consciously operated within an anachronistic structure by dressing ancient philosophers in contemporary rags.

In 1636, Ribera received a prestigious commission from the Neapolitan agents of Prince Karl Eusebius of Liechtenstein (1611–1684) for a series of “beggar-philosophers."

Although the original commission comprised 12 paintings, only six were delivered by 1637; the other six were never sent and may never have been executed.

Inscriptions help to identify three of the paintings—

Anaxagoras (fig. 1),

Crates, and

Diogenes—all of which are dated 1636 and signed with the Latin form of Ribera’s name (

Josephf). The Clowes painting is one of the three remaining works, which are dated 1637 and signed with the more typical Aragonese-Valencian form of the artist’s name (

Jusepe). The identification of the sitters in these three paintings is unclear. In the 1767 inventory of the Liechtenstein Collection, the six philosophers are named as

Aristotle,

Plato,

Crates,

Anaxagoras,

Diogenes, and

Protagoras. Only

Diogenes and

Anaxagoras are listed in the later inventories, where the above-mentioned

Aristotle is described as

Archimedes and the other paintings are generically labeled “philosophers.” The series was dispersed in 1954, and two of the enigmatic “philosophers” have subsequently been identified as

Plato (fig. 2) and

Protagoras (fig. 3).

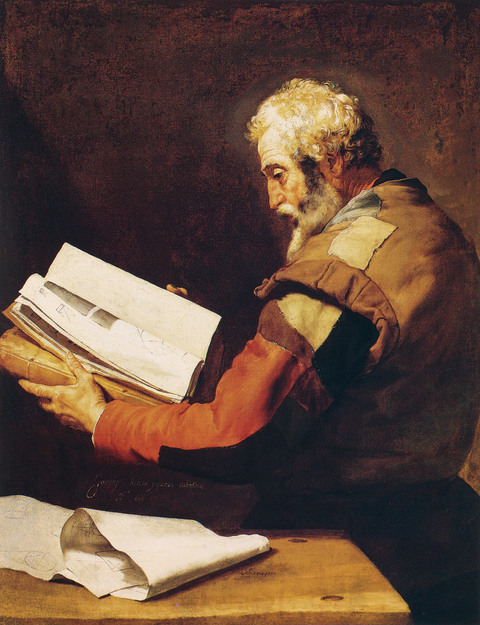

Figure 1: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Anaxagoras, 1636, oil on canvas, 47-1/4 × 37-13/32 in. Private collection.

Figure 1: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Anaxagoras, 1636, oil on canvas, 47-1/4 × 37-13/32 in. Private collection.

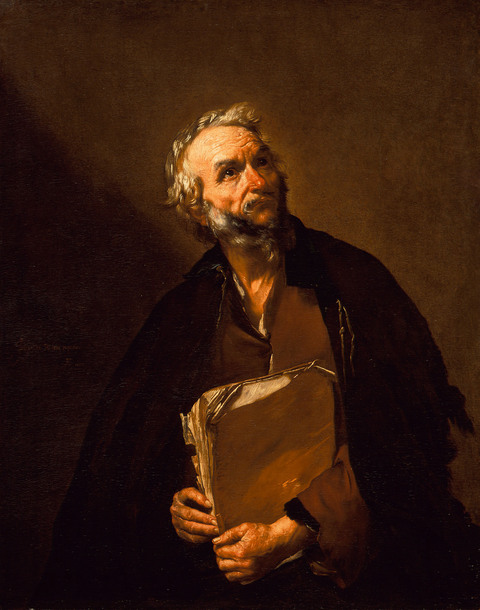

Figure 2: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Plato, 1637, oil on canvas, 48-15/16 × 39 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. R. Stanton Avery, M.91.125.2.

Figure 2: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Plato, 1637, oil on canvas, 48-15/16 × 39 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. R. Stanton Avery, M.91.125.2.

Figure 3: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Protagoras, 1637, oil on canvas, 48-7/8 × 38-3/4 in. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection, 1957.444.

Figure 3: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Protagoras, 1637, oil on canvas, 48-7/8 × 38-3/4 in. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection, 1957.444.

Determining the identity of the philosopher in the Clowes painting is especially challenging. Given the absence of textual evidence, we must rely primarily on visual clues. In appearance and on account of his scholarly associations, the philosopher recalls Ribera’s drawing of a seated man reading, also depicted in profile (fig. 4). Unlike the painted figure, however, the drawn figure’s profile view, sharp nose, pointed chin, and sunken cheeks give him a caricature-like quality. In the nineteenth century, the philosopher in the Clowes painting was thought to represent Archimedes, a reading supported by the geometric drawings on the paper in the foreground.

However, the art historian Delphine Fitz Darby argued in favor of Aristotle on account of the skullcap and doctor’s robe, which features a torn sleeve that she believed evokes the exposed arm on ancient statues of this same philosopher.

While the evidence remains inconclusive, for Darby, the identity of Ribera’s philosophers may have been purposefully ambiguous, thereby prompting a guessing game for his erudite patrons and audiences.

Figure 4: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), A Seated Man Reading and Two Cherubim, 1620s, pen and carbon-based ink on paper, 7-3/32 × 4-31/64 in. The Courtauld Gallery, London, The Samuel Courtauld Trust, D.1952.RW.367.

Figure 4: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), A Seated Man Reading and Two Cherubim, 1620s, pen and carbon-based ink on paper, 7-3/32 × 4-31/64 in. The Courtauld Gallery, London, The Samuel Courtauld Trust, D.1952.RW.367.

The Clowes painting represents a three-quarter-length figure, draped in a heavy robe and dramatically lit against a dark background in the manner of Caravaggio. In pose and type, the man echoes the painting of Anaxagoras in the same series, where the philosopher is also portrayed in profile. The curator Anthony Janson has observed the striking resemblance—in features and costume—to Diego Velázquez’s Water-Seller of Seville (London, Apsley House). Although Ribera would not have seen the original, perhaps he knew the work through painted copies that may have inspired his depiction of the philosopher, including such details as the torn sleeve.

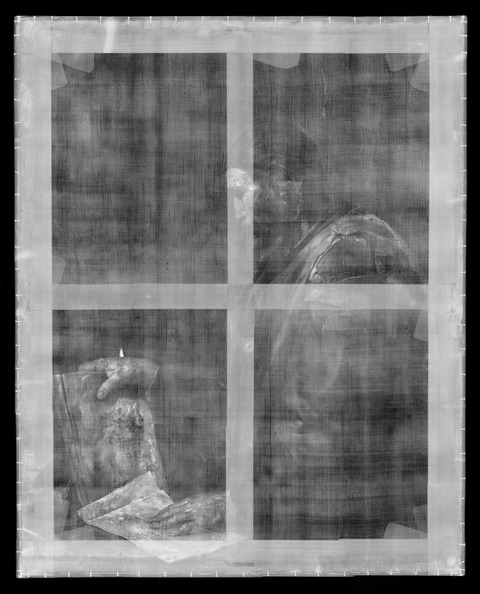

Ribera has restricted his palette to browns, grays, and blacks, and he has pared down the scene to focus our attention on the figure. An X-radiograph of the painting reveals that Ribera did not make any major alterations to the composition (fig. 5). Especially noteworthy is the way he has captured with precision the surfaces of skin, paper, and fabric. Typically, he used the bristles of his brush to simulate the bristly texture of the goatee, and he applied a rich

impasto to the figure’s forehead. Ribera has imbued the man with such lifelike qualities that we have the sense of beholding an actual living presence. Just as the figure is absorbed in thought, so, too, the viewer is captivated by the pictorial rendering, which simultaneously betrays the materiality of the paint and the artifice of its handling.

Figure 5: X-radiograph. Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), A Philosopher, probably Euclid, 1637, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.345.

Figure 5: X-radiograph. Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), A Philosopher, probably Euclid, 1637, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.345.

At the lower left, on the sheet of paper below the figure’s proper left hand, the artist has signed the painting—

Jusepe de Ribera español /

F. 1637—employing a trademark formula that underscores his Spanish nationality (fig. 6). Born in Játiva, Valencia, Ribera emigrated to Italy as a young artist in 1606. Proud of his Spanish heritage, he eventually settled in Naples, then a Spanish territory, in 1616, but never returned to Spain. The year 1637 was a watershed for Ribera. He completed several major paintings, including two versions of

Apollo and Marsyas (Naples, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte; Brussels, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique); a

Pietà (Naples, Cappella del Tesoro Nuovo, Certosa di San Martino); and

The Drinker (Oviedo, Colección Masaveu) and

Girl with a Tambourine (private collection), two genre paintings that may have originally formed part of an allegorical series dedicated to the five senses.

Figure 6: Photomicrograph of the artist’s signature, some of which has been

restored, and date (17 photomicrographs merged). Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652),

A Philosopher, probably Euclid, 1637, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.345.

Figure 6: Photomicrograph of the artist’s signature, some of which has been

restored, and date (17 photomicrographs merged). Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652),

A Philosopher, probably Euclid, 1637, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.345.

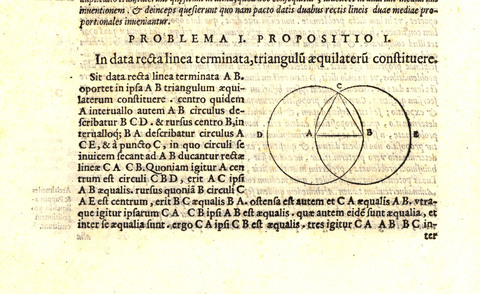

A second sheet of paper under the one with Ribera’s signature displays geometric drawings: a sketch of overlapping circles from which radiates a pentagonal shape, juxtaposed with a bisected rectangle and an indecipherable passage of text. Cropped by the painting’s edge is an ink-stained quill, an index of the tool that marked the pages framed by a geometer’s square. One of the square’s sides protrudes over the edge of the table, subtly breaking the picture plane and implicating the viewer’s space. The instrument thus creates a visual rhyme with the corner of the papers, which are tantalizingly angled to allow us a better view. Geometric drawings also feature in Ribera’s celebrated painting of

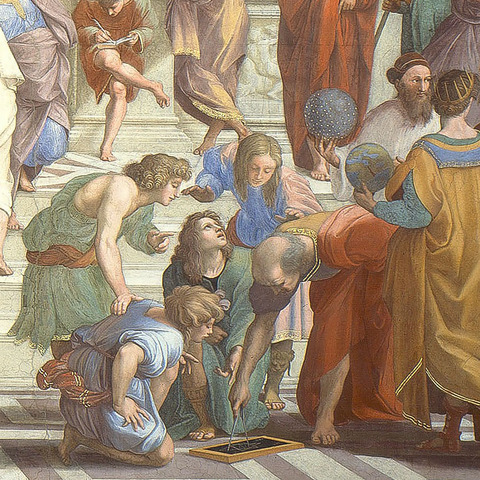

Democritus (Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado), where the philosopher is portrayed frontally, grinning and holding a compass. A detail from Raphael’s

School of Athens (fig. 7) represents the architect Bramante in the guise of Euclid, who similarly wields a compass while teaching geometry to his disciples. Moreover, a geometric diagram from Euclid’s

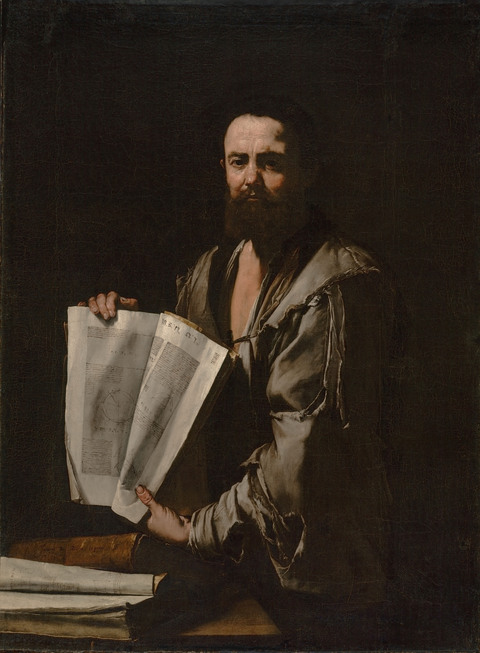

Elements (fig. 8) shows two intersecting circles and an equilateral triangle within the shared space, an illustration that resembles the sketch in the Clowes painting. A related work by Ribera represents a philosopher holding open Book 13, Proposition 10, of Euclid’s

Elements (fig. 9). Although the diagram in the Clowes painting does not offer such a precise match, it is close enough to the illustration in the

Elements to suggest that the figure depicted might portray, or allude to, Euclid.

Given his associations with visual and pictorial truth, this philosopher was considerably important within Ribera’s contemporary intellectual context, making him an appropriate subject for one of the paintings in a series destined for a learned patron.

Figure 7: Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio) (Italian, 1483–1520), The School of Athens (detail), 1509, fresco, 196-27/32 × 303-5/32 in. Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican.

Figure 7: Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio) (Italian, 1483–1520), The School of Athens (detail), 1509, fresco, 196-27/32 × 303-5/32 in. Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican.

Figure 8: Euclidian diagram of an equilateral triangle, Book 1 Proposition 1, from Euclidis Elementorum Libri XV: Unà com Scholijs Antiquis, à Federico Commandino Vrbinate Nuper in Latinum Conuersi, Commentarijsque Quibusdam Illustrati, ed. and trans. Federico Commandino (Pesaro: Apud C. Francischinum, 1572), 7.b. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, QA31.E831225 1572 F.

Figure 8: Euclidian diagram of an equilateral triangle, Book 1 Proposition 1, from Euclidis Elementorum Libri XV: Unà com Scholijs Antiquis, à Federico Commandino Vrbinate Nuper in Latinum Conuersi, Commentarijsque Quibusdam Illustrati, ed. and trans. Federico Commandino (Pesaro: Apud C. Francischinum, 1572), 7.b. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, QA31.E831225 1572 F.

Figure 9: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Euclid, about 1630–1635, oil on canvas, 49-1/4 × 36-3/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2001.26.

Figure 9: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Euclid, about 1630–1635, oil on canvas, 49-1/4 × 36-3/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2001.26.

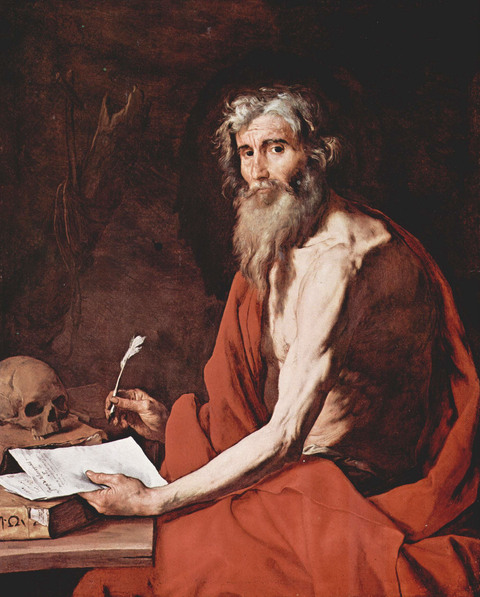

Ultimately, the design of the painting and its counterparts from the Liechtenstein commission recalls an

Apostolado, a series of portrait-like images of saints or apostles. Indeed, there is an intriguing parallel between the Clowes painting and Ribera’s

St. Jerome (fig. 10). Ordered by the prior of the Certosa di San Martino in 1638 (but not completed until 1651), that painting depicts a scholarly Jerome, seated behind a table with a quill and parchment in hand. Exceptionally, he lifts his head to meet the spectator’s gaze—the only image of St. Jerome by Ribera in which the figure makes direct eye contact with the beholder. More significant, however, is the subtle position of the signature on the paper, which recalls the location of the signature in the Clowes painting. It seems as if Jerome, with his quill poised above the page, has effectively inscribed the name of his creator. Is this device intentionally deployed to equate the artist’s name with the sacred words written by the saint? Or is Ribera merely expressing his profound affinity with Jerome? Throughout his career, Ribera represented St. Jerome more frequently than any other subject. Both figures were translators of the Bible, one into visual images, the other into textual form, and it is noteworthy that the signature appears on a page of Jerome’s translation of the scriptures, recalling the ancient theme of the Divine Artist. This concept relates to the notion that aesthetic beauty may deceive viewers into believing that a work of art is created by divine intervention rather than human hands. However, beyond a superficial reading of the painter inscribed within his painting—thus invoking the adage

ogni pittore dipinge sè (“every painter paints himself”)—the signature reminds us that this work of art was conceived by Ribera, not God.

When examining the painting of

St. Jerome, it is not only the figure’s address to the spectator that so captivates our attention, but also the freely brushed surface of the canvas and the material properties of paint. While Jerome appears in the foreground, Ribera, too, is center stage. Likewise, the prominence of Ribera’s signature in the Clowes painting is further emphasized by the philosopher, who indicates the artist’s name with his left hand. There is a subtle conflation of painter and philosopher, who seems to have signed the sheet (and the painting) himself.

Figure 10: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Saint Jerome, 1651, oil on canvas, 49-7/32 × 39-3/8 in. Polo Museale della Campania—Museo di San Martino, Naples.

Figure 10: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Saint Jerome, 1651, oil on canvas, 49-7/32 × 39-3/8 in. Polo Museale della Campania—Museo di San Martino, Naples.

With his right hand, the figure supports a large book in a manner that resembles Ribera’s painting of

Heraclitus (fig. 11), the “weeping philosopher” who is often paired with Democritus, the “laughing philosopher.” As in the Clowes painting, Heraclitus wears a skullcap and raises the cover of his tattered tome on which is inscribed the artist’s name at lower left. The signature thus announces the authorship of the painting and its “double,” which takes the form of a large book. Indeed, both philosophers angle the blank cover of a closed volume in a manner that suggests a tabula rasa. An iconic painting by Velázquez from the following decade—

Female Figure (

Sibyl with Tabula Rasa) (fig. 12)—depicts one of the ancient Sibyls, the mythological prophetesses believed to have foretold aspects of Christian history. She is portrayed with a tabula rasa, her index finger hovering like a paintbrush over the tablet, her hand casting a shadow on its blank surface. Although the subject is debated, it may be interpreted as an allegory of painting, invoking the passage from the ancient Roman author Pliny’s

Natural History: “The question as to the origin of the art of painting is uncertain…but all agree that it began with tracing an outline round a man’s shadow and consequently that pictures were originally done in this way."

This concept resonated in a Spanish treatise by the artist-theoretician Vicente Carducho,

Diálogos de la pintura (1633), which includes an engraved endpiece depicting a tabula rasa with a suspended paintbrush casting a shadow. The image bears the Latin inscription

POTENTIA AD ACTUM TAMQUAM TABULA RASA, relating Aristotle’s philosophy of potentiality versus actuality to the artist’s encounter with a blank canvas upon which he may freely create within the limits of his imagination.

Given the location of the signature in the Clowes painting, perhaps the philosopher is a stand-in for the painter, the closed book analogous to the blank canvas, the cast shadow an allusion to the art of painting. We are meant to imagine what lies inside the book, just as we project an image onto the tabula rasa with our mind’s eye. Although the philosopher presents the viewer with a closed book, he gazes at its empty cover, absorbed in thought, thus mirroring the viewer’s action before the painted canvas, which bears the traces of the artist’s divine inspiration.

Figure 11: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Heraclitus, 1634, oil on canvas, 49-7/32 × 37-13/64 in. Private collection.

Figure 11: Jusepe de Ribera (Spanish, 1591–1652), Heraclitus, 1634, oil on canvas, 49-7/32 × 37-13/64 in. Private collection.

Figure 12: Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Spanish, 1599–1660), Female Figure (Sibyl with Tabula Rasa), about 1648, oil on canvas, 25-1/2 × 23 in. Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas. Algur H. Meadows Collection, MM.74.01.

Figure 12: Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Spanish, 1599–1660), Female Figure (Sibyl with Tabula Rasa), about 1648, oil on canvas, 25-1/2 × 23 in. Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas. Algur H. Meadows Collection, MM.74.01.

Author

Edward Payne

Provenance

Commissioned from Ribera in 1636 by Karl Eusebius von Liechtenstein (1611–1684), Schloss Feldsberg (now in Czech Republic) via his agents Lorenzo Cambi and Simone Verzone;

By descent within the family of the princes of Liechtenstein, Vaduz, Liechtenstein;

Sold to (Newhouse Galleries, New York) in 1954;

G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1955;

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2000, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10066);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2000.

Exhibitions

Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, 1957, Exhibition of Paintings and Graphics by Jusepe Ribera, no. 4;

John Herron Museum of Art, Indianapolis, 1959, Paintings from the Collection of George Henry Alexander Clowes: A Memorial Exhibition, no. 49, as Archimedes;

The Art Gallery, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1962, A Lenten Exhibition, no. 42, as Archimedes;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1962, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, no. 31;

John Herron Museum of Art, Indianapolis, and Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, 1963, El Greco to Goya, no. 70, as Archimedes;

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, 1982, Jusepe de Ribera, lo Spagnoletto 1591–1652, no. 18, as A Philosopher (Aristotle?);

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1992, Jusepe de Ribera, 1591–1652, no. 40, as Aristotle;

Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas, 2017, Between Heaven and Hell: The Drawings of Jusepe de Ribera, as Aristotle;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection, as A Philosopher, probably Euclid;

Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, China; Hunan Museum, Changsha, China; Chengdu Museum; 2020–2021, Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting, as A Philosopher, probably Euclid.

References

Vincenzio Fanti, Descrizzione completa di tutto ciò che ritrovasi nella galleria di pittura e scultura di sua altezza Giuseppe Wenceslao del S. R. I. principe regnante della casa di Lichtenstein (Vienna: Stamperia aulica di Giovanni Tommaso de Trattnern, 1767), 105, no. 531;

Description des tableaux et des pieces de sculpture que renferme La Gallerie de Son Altesse François Joseph chef et Prince Regnant de la Maison de Liechtenstein (Vienna: Chez Jean Thom. nob. de Trattnern, imprimeur et libraire de la cour, 1780), 160, 169;

Louis Viardot, Les musées d’Allemagne et de Russie (Paris: Paulin, 1844), 257;

August L. Mayer, Jusepe de Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto) (Leipzig: Karl. W. Hiersemann, 1908), 188;

August L. Mayer, Jusepe de Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto) (Leipzig: Karl W. Hiersemann, 1923), 99–100, 201;

A. Kronfeld, Führer durch die fürstlich Liechtensteinsche Gemäldegalerie in Wien (Vienna: Kunstverlag Wolfrum, 1927 and 1931), 23, no. A57;

Bernardino de Pantorba, José de Ribera: Ensayo biográfico y crítico (Barcelona: Iberia–Joaquín Gil, 1946), 25;

Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin 14, no. 2 (Winter 1957): 74;

Juan Antonio Gaya Nuño, La pintura española fuera de España (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, S.A., 1958), no. 2324;

Evan H. Turner, “Ribera’s Philosophers,” Wadsworth Atheneum Bulletin 4, no. 1 (Spring 1958): 5n5, 8, fig. 2, as Archimedes the Philosopher;

Delphine Fitz Darby, “Ribera and the Wise Men,” Art Bulletin 44, no. 4 (December 1962): 298–299 and fig. 9 as The Philosopher Aristotle;

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

Craig M. Felton, “Jusepe de Ribera, a Catalogue Raisonné,” PhD dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1971, 420–421, no. X18, as an unaccepted attribution;

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 60–61, as Archimedes (reproduced);

Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez and Nicola Spinosa, eds., L’opera completa del Ribera (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1978), 139, no. 403, as Archimedes (reproduced);

Anthony F. Janson and A. Ian Fraser, 100 Masterpieces of Painting: Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1980), 71–74, as Archimedes (reproduced);

Craig Felton and William B. Jordan, eds., Jusepe de Ribera, lo Spagnoletto 1591–1652, exh. cat. (Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum, 1982), 156–57, no. 18, as A Philosopher (Aristotle?) (reproduced);

Eduardo Nappi, “Pittori del ‘600 a Napoli: Notizie inedite dai documenti dell’Archivio storico del Banco di Napoli,” Ricerche sul ’600 napoletano 2 (Milan: L & T, 1983), 73–87;

Antonio Delfino, “Documenti inediti per alcuni pittori napoletani del ‘600 e l’inventario dei beni lasciati de Lanfranco Massa,” Ricerche sul ’600 napoletano 4 (Milan: L & T, 1985), 104;

Craig Felton, “Ribera’s ‘Philosophers’ for the Prince of Liechtenstein,” Burlington Magazine 128, no. 1004 (November 1986): 785–789, fig. 7, as Aristotle;

Oreste Ferrari, “L’iconografia dei filosofi antichi nella pittura del secolo XVII in Italia,” Storia dell’arte 57 (1986): 114, 150, fig. 30, as Aristotle;

Holliday T. Day, ed., Indianapolis Museum of Art Collections Handbook (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1988), 25, as A Philosopher (Archimedes?) (reproduced);

Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez and Nicola Spinosa, eds., Jusepe de Ribera, 1591–1652, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992), 115–119, no. 40 as Aristotle (reproduced);

Nicola Spinosa, Ribera: L’opera completa (Naples: Electa Napoli, 2003), 304, no. A176 as Aristotle (reproduced);

Ellen W. Lee, ed., Indianapolis Museum of Art Highlights of the Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2005), 104, as Aristotle (reproduced);

Nicola Spinosa, Ribera: L’opera completa (Naples: Electa Napoli, 2006), 332, no. A198, as Aristotle (reproduced);

Nicola Spinosa, Ribera: La obra completa (Madrid: Fundación Arte Hispánico, 2008), 417–418, no. A218, as Aristotle (reproduced);

Zahira Véliz, Spanish Drawings in The Courtauld Gallery: Complete Catalogue (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2011), 224, fig. 145, as Aristotle;

Ximo Company and María Antonia Argelich, José de Ribera, San Jerónimo estudiando (Lleida: Centre d’Art d’Època Moderna, Universitat de Lleida, 2013), 23, fig. 24, as Aristotle;

Gabriele Finaldi, ed., Jusepe de Ribera, The Drawings: Catalogue raisonné (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado/Seville: Fundación Focus/ Dallas: Meadows Museum, SMU, 2016), 136, fig. 43.1, as Aristotle;

Kjell M. Wangensteen, et al., Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 118–119 (reproduced);

Kjell M. Wangensteen, et al., Floating Lights and Shadows: 500 Years of European Painting (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing, 2020), 116–117 (reproduced).

Notes