Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

Author

Provenance

(Jakob M. Heimann (1881–1960), Milan, later New York), by 1939;20

Via (Ivan N. Podgoursky, Boston) to G.H.A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1939;21

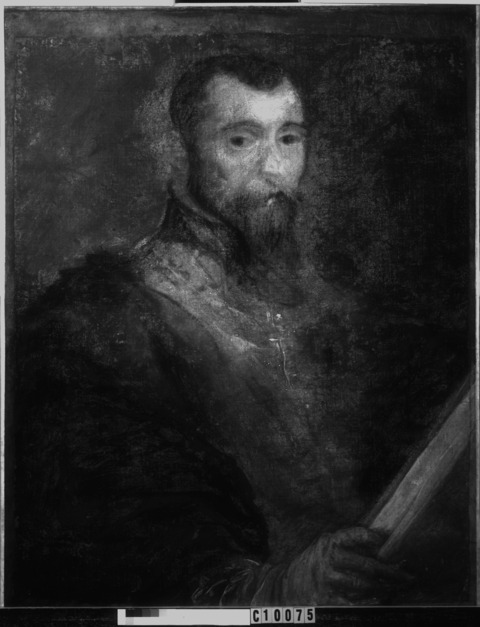

The Clowes Fund, Indianapolis, from 1958–2014, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10075);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2016.

Exhibitions

Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH, 1940, Four Centuries of Venetian Painting, no. 67;

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, 1965, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection, no. 19;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection.

References

Adolfo Venturi, “Tre ritratti inediti di Tiziano,” l’Arte, n. s. 8 (1937): 56, fig. 3;

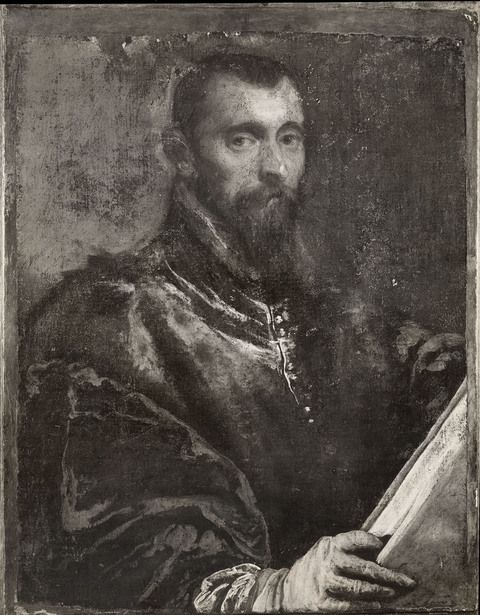

Hans Tietze, Four Centuries of Venetian Painting, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1940), cat. no. 67 (reproduced as Titian, Portrait of an Unknown Gentleman; however, the catalogue entry indicates “follower of Titian”);

Bernard Berenson, Pitture Italiane del Rinascimento (London: Phaidon/Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1958), 1:179 (listed as Indianapolis, Indiana. Dr. G.H.A. Clowes, Bust of a Bearded Man with Book);

Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Collection (Bloomington: Indiana University Art Museum, 1965), no. 19 (as Titian, Nobleman with the Glove);

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, 1968);

Paola Rossi, Jacopo Tintoretto (Venice: Alfieri, 1974), 1: cat. no. 224 (reproduced as School of Jacopo Tintoretto, Bust of a bearded man with book, Indianapolis, G.H.A. Clowes Collection?).

Technical Notes and Condition

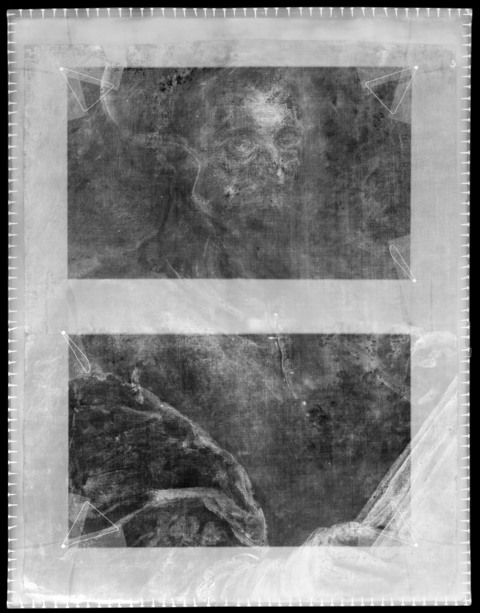

The painting is in stable condition. There is no evidence of cusping or original tack holes. The original plain-weave canvas has been significantly trimmed along all four sides and relined. A natural cracking network beginning in the ground layer is visible. Infrared reflectography reveals the figure was generally sketched using a wet, carbon-based medium. No pentimenti are discernible, but there are slight adjustments and reinforcements using paint. Surface paint was applied using brushes of varying size with some slight impasto. The paint layer in the area of the face has been delicately applied. There are large areas of loss and abrasion throughout the painting.

Notes

-

Cesare Vecellio, Habiti Antichi et Moderni (Venice, 1590). I am grateful to Linda Witkowski and David Miller for their shared insights regarding the technical analysis of this painting. I am indebted to Dr. Carlo Corsato for his perceptive comments on an earlier version of this essay. During the final stages of this essay’s preparation, I benefited greatly from the thoughtful expertise of Professor Paul Joannides. ↩︎

-

For the purchase agreement and signed certificates of authenticity by Lionello Venturi, Giuseppi Fiocco, Antonio Morassi, Wilhelm Reinhold Valentiner, Amadore Porcella, and William Suida, see File 2016.163, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. See also Adolfo Venturi, “Tre ritratti inediti di Tiziano,” L’Arte, n. s. 8 (1937): i, 55–59, specifically 56. ↩︎

-

Hans Tietze, Four Centuries of Venetian Painting, exh. cat. (Toledo: Toledo Museum of Art, 1940), cat. no. 67. ↩︎

-

The earliest documented treatment dates to 1941 by Vincent Riportella in New York, but details of this treatment are unknown. See correspondence in File 2016.163, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Suhr’s papers are at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. Titian, Portrait of a Man, William Suhr Papers, Series 1, Box 80, Special Collections, Getty Research Institute, The J. Paul Getty Trust. ↩︎

-

Suhr’s recorded dates for treatment are “In 18 April 1956; Out 7 November 1956.” Titian, Portrait of a Man, William Suhr Papers, Series 1, Box 80, Special Collections, Getty Research Institute, The J. Paul Getty Trust. As to his question of authorship, he filed a second copy of his treatment report under the artist Giovan Girolamo Savoldo (active about 1480–after 1548). Giovan Girolamo Savoldo, Portrait of a Man, William Suhr Papers, Series 1, Box 76, Special Collections, Getty Research Institute, The J. Paul Getty Trust. ↩︎

-

Linda Witkowski, treatment report, C10075 (2016.163), November 1989, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Jill Dunkerton and Marika Spring, “The Development of Painting on Coloured Surfaces in Sixteenth-Century Italy,” in Painting Techniques: History, Materials, and Studio Practice, ed. Ashok Roy and Perry Smith (London: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1998), 120–130. ↩︎

-

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” unpublished manuscript, 1968, Clowes Registration Archive, IMA. ↩︎

-

On Leandro Bassano, Arslan remains the leading source. Wart Arslan, I Bassano (Milan: Ceschina, 1960), 245–267. See also Livia Alberton Vinco da Sesso, “Leandro Bassano,” Dizionario Bibliografico degli Italiani, accessed 23 June 2017, http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/dal-ponte-leandro-detto-bassano (Dizionario-Biografico). ↩︎

-

On the Bassano workshops, see Carlo Corsato, “Dai Dal Ponte ai Bassano: L’eredità di Jacopo, le botteghe dei figli e l’identità artistica di Michele Pietra, 1578–1656,” Artibus et Historiae 73 (2016): 195–248; and Carlo Corsato, “Production and Reproduction in the Workshop of Jacopo Bassano,” in Jahrbuch des Kunsthistorischen Museums Wien 12 (Mainz am Rheim: Philipp von Zabern, 2010): 41–53. ↩︎

-

Carlo Ridolfi, Le Maraviglie dell’Arte, ed. Detlev Freiherrn von Hadeln (Rome: Società Multigrafica Editrice Somu, 1965), 165–171. ↩︎

-

Object information given here is taken from the respective websites of the holding institutions. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, “Leandro Bassano, Portrait of Prospero Alpino, 1592 (Inv. Nr. 143),” accessed 21 March 2022, https://www.staatsgalerie.de/g/sammlung/sammlung-digital/einzelansicht/sgs/werk/einzelansicht/026BF9074BCF47FBB1DD9DF53C58E3E3.html. Royal Collection Trust, “Leandro Bassano, Portrait of Tiziano Aspetti holding a statuette, about 1592–1593 (RCIN 405988),” accessed 21 March 2022, https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/405988/portrait-of-tiziano-aspetti-holding-a-statuette. Claudia Kryza-Gersch, “Leandro Bassano’s Portrait of Tiziano Aspetti,” The Burlington Magazine 140, no. 1141 (April 1998): 265–267. At the time of Roskill’s manuscript, the Aspetti portrait was known as the Man with a Sculpture, and it is currently located in London at Buckingham Palace. Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968). Munich, Alte Pinokothek, “Leandro Bassano, Portrait of the Merchant Leonhard Hermann, about 1595 (8091),” accessed 21 March 2022, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/Qr4DyWoxpE. By way of comparison, a smaller half-length portrait is the Portrait of Alvise Corradini, about 1612, 22-13/16 × 16-7/8 in. (58 × 43 cm), Padua, Museo Civico. Giorgio Cini, “Ritratto di Alvise Corradini,” accessed 21 March 2022, http://arte.cini.it/Opere/405548. ↩︎

-

Workshop methods tended toward established models. Because Leandro trained with his father, one suspects that he used his native Vicentine braccio (69 cm). I am grateful to Carlo Corsato for this suggestion. It is also possible that the canvas was sourced in Venice, in which case the braccio measured 63.8 cm. Angelo Martini, Manuale di metrologia, ossia misure, pesi e monete in uso attualmente e anticamente presso tutti i popoli (Turin: Loescher, 1883), 817 and 823, accessed 21 March 2022, http://www.braidense.it/dire/martini/modweb/pagine/817.htm, http://www.braidense.it/dire/martini/modweb/pagine/823.htm. Canvas paintings tended toward uniform sizes to economize fabric and minimize leftover strips. ↩︎

-

Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, “Leandro Bassano, Portrait of an Old Man (53.477),” accessed 21 March 2022, https://www.mfab.hu/artworks/portrait-of-an-old-man-2/. ↩︎

-

Paola Rossi, Jacopo Tintoretto (Venice: Alfieri, 1974), 1: cat. no. 224. ↩︎

-

Author’s translation. “…a prima vista, far pensare al Tintoretto, piu che altro, anzi soltanto, analogie di modello: ma altra ed inconfondibile e' la gamma croma e la pennellata tipica di Tiziano….” Amadore Porcella, certificate of expertise, File 2016.163, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Author’s translation. “Nè il Tintoretto, nè il Bassano possano essere autori del nostro dipinto benché questo significa uno dei punti di contatto fra Tiziano e quelli due suoi grandi continuatori.” William Suida, certificate of expertise, File 2016.163, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

For a comparative discussion on the portraits of Leandro Bassano and Domenico Tintoretto, see Meri Sclosa, “Per la ritrattistica di Leandro Bassano e Domenico Tintoretto,” in Jacopo Bassano I figli, la scuola, l’eredità, conference proceedings from the international study at Bassano del Grappa, Università degli Studi, Archivio Antico del Bò, 30 March–2 April 2011, ed. Claudia Caramanna, Federica Millozzi, and Giuliana Ericani (Bassano del Grappa: Bollettino del Museo Civico, 2010), 1:130–140 and 286–295. Also see Meri Sclosa, “Vedute possibili: Finestre paesaggistiche nella ritrattistica di Leandro Bassano e Domenico Tintoretto,” Paragone 94 (November 2010): 33–52. ↩︎

-

The back of a photograph of this painting, bearing an expertise by Lionello Venturi dated 5 June 1939 and attributing the painting to the “late period of Titian,” shows a sticker with the following information: “Jakob Heimann, Milano, Via Serbelloni 13.” See File C10075, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Podgoursky to G.H.A. Clowes, 12 November 1939, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Clowes promptly lent this painting to an exhibition in Toledo in 1940; see Hans Tietze, Four Centuries of Venetian Painting, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1940), no. 67. ↩︎