Marks, Inscriptions, and Distinguishing Features

None

Entry

10“Portrait of a Man, Umbrian School, end of the 15th century. The figure, a beardless young man, whose face is framed by long, curly hair wearing a cap with a narrow brim, is seen in half-length. Dressed in a dark green doublet with a small gold-embroidered collar and light green sleeves, he turns his head to the right and tilts it back, the mouth in an ecstatic attitude. Dark green background. Oak panel, Diam. 47 [cm]."29

Author

Provenance

Probably Emile Gavet (1830–1904), Paris.45

Probably Count Tassilo Festetics (1850–1933), Budapest.46

Possibly (Duveen Brothers, Paris) in the inter-war period.47

(E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York);

G.H. A. Clowes, Indianapolis, in 1942;48

Clowes Fund Collection, Indianapolis, in 1958, and on long-term loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1971 (C10001);

Given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, in 2014.

Exhibitions

Indiana University Museum of Art, Bloomington, 1962, Italian and Spanish Paintings from the Clowes Fund Collection, no. 6;

Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 2002 [extended to 26 January 2003], Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento;

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, 2019, Life and Legacy: Portraits from the Clowes Collection, as Circle of Uccello.

References

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968);

A. Ian Fraser, A Catalogue of the Clowes Collection (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1973), 26 (reproduced);

C. Volpe, “Paolo Uccello a Bologna”. Paragone, XXXI, 365 (July 1980): 3–28, in particular 16, fig. 6 (reproduced);

Alessandro Angelini, Pittura di luce: Giovanni di Francesco e l’arte fiorentina di metà Quattrocento, ed. Luciano Bellosi (Milan: Electa, 1990), 73–77;

Miklós Boskovits “Da Masaccio a Piero dell Pollaiolo: Studi sul ritratto Fiorentino Quattrocentesco,” Arte Cristiana 85, no. 781 (July–August 1997): 255–63, fig. 1 (reproduced);

Laurence B. Kanter, “The ‘cose piccole’ of Paolo Uccello. Apollo (August 2000): 11–20, fig. 14 (reproduced);

Miklós Boskovits, “Appunti sugli inizi di Masaccio e sulla pittura fiorentina del suo tempo,” in Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento, ed. Luciano Bellosi, Lauro Cavazzini, and Aldo Galli, exh. cat. Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 20 September–21 December 2002 (Milan: Skira, 2002), 53–75, in particular 67;

Miklós Boskovits, “Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Young Man, about 1430–1435,” in Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento, ed. Luciano Bellosi, Lauro Cavazzini, and Aldo Galli, exh. cat. Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 20 September–21 December 2002 (Milan: Skira, 2002), 194–95, cat. no. 32 (reproduced);

Angelo Tartuferi, “La mostra ‘Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento’ a San Giovanni Valdrano,” Gazzetta antiquaria 42, no. 2 (November 2002): 34–39;

Miklós Boskovits and David Alan Brown, ed., Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century, (Oxford University Press: New York and Oxford, 2003), 456n20, 593n17.

Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic (Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008), 2, 177–80, 278–80, cat. no.16; (reproduced);

Mauro Minardi, Paolo Uccello (Milan: 24 Ore Cultura, 2017), 113–15, fig. 97 (reproduced).

Notes

-

I am thankful to the following for their technical expertise and shared observations: David Miller, former Chief Conservator and Senior Paintings Conservator; Linda Witkowski, Senior Paintings Conservator; Erica Schuler, former Clowes Fellow in Paintings Conservation; and Dr. Gregory Dale Smith, the Otto N. Frenzel III Senior Conservation Scientist. I am grateful to Dr. Dóra Sallay of the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, and Ágota Varga for their insights including those on the Festetics Collection. During the final stages of this essay’s preparation, I benefited greatly from the thoughtful expertise of Professor Paul Joannides. ↩︎

-

On portraiture see John Pope-Hennessy, The portrait in the Renaissance. The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, Bollingen Ser 35, no. 12 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979), 3–100; Gottfried Boehm, Bildnis und Individuum (Munich, 1985), 209–13. ↩︎

-

On Alberti’s bronze self-portrait see National Gallery of Art, Washington, “Leon Battista Alberti, Self-Portrait, ca. 1435,” accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.nga.gov/Collection/art-object-page.43845.html. ↩︎

-

Proponents for the Uccello attribution include Carlo Volpe, “Paolo Uccello a Bologna,” Paragone, vol. 31, no. 365 (July 1980), 3–28, in particular 16; Alessandro Angelini, Pittura di luce: Giovanni di Francesco e l’arte fiorentina di metà Quattrocento, ed. Luciano Bellosi (Milan: Electa, 1990), 73–77, in particular 73; Miklós Boskovits, “Studi sul ritratto fiorentino quattrocentesco–I parte,” Arte Cristiana85, no. 781 (July–August 1997): 255–63, in particular 255; Laurence B. Kanter, “The ‘cose piccole’ of Paolo Uccello. Apollo (August 2000): 11–20, in particular 17, fig. 14; Miklós Boskovits, “Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Young Man, about 1430-1435,” in Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento, ed. Luciano Bellosi, Lauro Cavazzini and Aldo Galli, exh. cat. Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 20 September–21 December 2002 (Milan: Skira, 2002), 194-6, cat. no. 32; Miklós Boskovits, Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century, ed. Miklós Boskovits and David Alan Brown (Oxford University Press: New York and Oxford, 2003), 456n20, 593n17; Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic, (Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008), 2, 177–80, 278–80, cat. no. 16; and Mauro Minardi, Paolo Uccello (Milan: 24 Ore Cultura, 2107), 113–15, fig. 97. ↩︎

-

“buono componitore e vario,” Cristoforo Landino, Scriti, Critici e Teorici, ed. Roberto Cardini, vol. 1 (Bulzoni, 1974), 124. “In molte case di Firenze sono assai quadri in perspettiva per vani di lettucci, letti, ed alter cose piccolo, di mano del medesimo…” Giorgio Vasari, Le opera de Giorgio Vasari, vol. 3, ed. Gaetano Milanesi, vol. 2 [1550 and 1568] (Florence, Sansoni, 1966–1987), 203–19, in particular 213–14. On Uccello’s oeuvre see Mario Salmi, Paolo Uccello, Andrea del Castagno, Domenico Veneziano (Rome: Casa editrice d'arte “Valori plastici,” 1936); Wilhelm Boeck, Paolo Uccello: Der Florentiner Meister und Sein Werk (Berlin, 1939); John Pope-Hennessy, The Complete Work of Paolo Uccello (London and New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 1969); Anna Padoa Rizzo, Paolo Uccello: Catalogo completo dei dipinti (Florence: Cantini, 1991); and Franco and Stefano Borsi, Paolo Uccello (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994); Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic, (Saarbrücken: VDM, 2008); and Mauro Minardi, Paolo Uccello (Milan: 24 Ore Cultura, 2017). Also see Georg Pudelko, “The Early Works of Paolo Uccello,” The Art Bulletin16, no. 3 (September 1934): 230–59. Lorenzo Sbaraglio, “Paolo di Dono detto Paolo Uccello,” Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 81, accessed 26 January 2022, http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/paolo-di-dono-detto-paolo-uccello_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/. A critical reception of Uccello’s work is offered by Roberto Longhi, Fatti di Masolino e Masaccio e altri studi sul Quattrocento (Florence: Sansoni, 1975), 44–45. See English translation cited in Laurence B. Kanter, “The ‘cose piccole’ of Paolo Uccello. Apollo (August 2000): 11–12 per Roberto Longhi, Three Studies, trans. David Tabbat and David Jacobson (Riverdale-on-Hudson, NY: Stanley Moss-Sheep Meadow Press, 1995), 60–61. ↩︎

-

Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic, (Saarbrücken: VDM, 2008), 11–13. ↩︎

-

Painting information given here is taken from the websites of the holding institutions. National Gallery of London, “Paolo Uccello, The Battle of San Romano, probably about 1438–1440 (NG583), accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/paolo-uccello-the-battle-of-san-romano; Louvre Museum, Paris, “Paolo Uccello, La Bataille de San Romano: la contre-attaque de Micheletto Attendolo da Cotignola, 1450–1475 (M.I. 469)”, accessed 26 January 2022, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065339; and Uffizi Gallery, Florence, “Paolo Uccello, Battle of San Romano, ca. 1435–1440 (1890 no. 479)”, accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/battle-of-san-romano. ↩︎

-

Lorenza Melli, “Nuove indagini sui disegni di Paolo Uccello agli Uffizi: disegno sottostante, technical, funzione,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Istitutes in Florenz, vol. 42, no. 1 (1998): 1–39. Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic (Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008, 2008), 130–46. ↩︎

-

Portraits in the San Romano scenes are those speculatively identified as the condottieri Niccolò da Tolentino (probably after 1375–1435) and Micheletto Attendolo, also known as Micheletto da Cotignola (about 1390–1451) (London’s National Gallery of Art and the Louvre in Paris, respectively). Also see Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic, (Saarbrücken: VDM, 2008), 169–70, 266–67, cat. nos. 9–11. ↩︎

-

The comparative figures include a male in the Disputation of Saint Stephen shown wearing a red turban and various medallion portrait busts located in the border framing these scenes. Miklós Boskovits, “Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Young Man, about 1430–1435,” in Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento, ed. Luciano Bellosi, Lauro Cavazzini and Aldo Galli, exh. cat. Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 20 September–21 December 2002 (Milan: Skira, 2002), 196. No known contract or surviving documentation specifically names Paolo Uccello as the author of the Marcovaldi Chapel frescoes. However, he was reportedly in Prato between the winter of 1435 and spring of 1436. Today, these frescoes are generally attributed to Uccello with portions by Andrea di Giusti. Anna Padoa Rizzo, La Cappella dell’Assunta nel Duomo di Prato (Prato, 1997), 9, 35–40. Angelini dates the frescoes around 1433; see Alessandro Angelini, “Paolo Uccello, il beato Jacopone da Todi, e la datazione degli affreschi di Prato,” Prospettiva, no. 61 (January 1991): 49–53, in particular 51 and n24. Also see Mauro Minardi, Paolo Uccello (Milan: 24 Ore Cultura, 2017). ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits, “Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Young Man, about 1430–1435,” in Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento, ed. Luciano Bellosi, Lauro Cavazzini and Aldo Galli, exh. cat. Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 20 September–21 December 2002 (Milan: Skira, 2002), 196. Also see Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic, (Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008), 279, 259–262, cat. no. 5. ↩︎

-

Paul Joannides, Masaccio and Masolino: A Complete Catalogue (London: Abrams, 1993), 350–51. ↩︎

-

Most recently see Laurence B. Kanter, “The ‘cose piccole’ of Paolo Uccello,” Apollo (August 2000). Also see Jean Lipman, “The Florentine Profile Portrait in the Quattrocento,” The Art Bulletin18, no. 1 (March 1936): 54–102. Rab Hatfield, “Five Early Renaissance Portraits,” The Art Bulletin 47, no. 3 (Sep 1965): 315-334. Florentine, Matteo Olivieri (?), about 1430s, tempera (and oil?) on panel transferred to canvas, 18 7/8 × 13 7/16 in. (48 × 34.1 cm), National Gallery, Washington, DC, 1937.1.15. National Gallery, “Florentine, Matteo Olivieri (?), c. 1430s,” accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.nga.gov/Collection/art-object-page.17.html. Master of the Castello Nativity, Portrait of Michele Olivieri, about 1450, tempera on panel, 17 3/4 × 12 3/4 in. (45.1 × 32.4 cm), Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, 83.584. Chrysler Museum, “Master of the Castello Nativity, Portrait of Michele Olivieri, c. 1450,” accessed 26 January 2022, http://chrysler.emuseum.com/objects/14849/portrait-of-michele-olivieri?ctx=38088f15-adc2-43ae-9967-07d6cfbcfbbc&idx=0. Portrait of a Man, about 1430, tempera on panel, 47 × 36 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Chambéry, 930. Paul Joannides, Masaccio and Masolino a Complete Catalogue (London: Abrams, 1993), 458, no. U3. Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic, (Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008), 210, 220n47, 334–35, cat. no. 66. ↩︎

-

Painting information given here is taken from the website of the holding institution. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, “The Hunt in the Forest, c. 1465–1470 (WA1850.31),” accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.ashmolean.org/hunt-forest. ↩︎

-

Painting information given here is taken from the website of the holding institution. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, “Attributed to Paolo Uccello, A Young Lady of Fashion, early 1460s (P27W58),” accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience

/collection/12396. Kanter favors the Uccello attribution. Laurence B. Kanter, “The ‘cose piccole’ of Paolo Uccello. Apollo (August 2000): 19. Hudson and Minardi instead favor an attribution to the Master of Castello Nativity; see Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic, (Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008), 325, cat. no. 56. Mauro Minardi, Paolo Uccello (Milan: 24 Ore Cultura, 2017), 280–82, fig. 209. For a comparison, see Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, “Master of the Castello Nativity, Portrait of a Woman, probably 1450s (49.7.6)” accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437000. ↩︎ -

Letter from Edith Whitehill Clowes to Mr. Silberman, 2 February 1965, File 2014.87 (C10077), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Venturi’s certificate of authenticity (dated 20 June 1941) is attached to the letter written by Dr. Clowes to Dr. Luisa Vertova, 24 March 1954, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. A second copy of Venturi’s certificate is not dated. See File 2014.87 (C10077), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Hudson cites the date as date 20 June 1940 per a copy of Venturi’s letter at the Villa I Tatti Fototeca. Hugh Hudson, Paolo Uccello: Artist of the Florentine Renaissance Republic (Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008, 2008), 278. Letter from Hans Tietze to Mr. Silberman, 27 June 1941, File 2014.87 (C10077), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Letter from William Suida, n.d., File 2014.87 (C10077). Also see William Suida to Mr. Silberman, 10 September 1941, File 2014.87 (C10077). Both in Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968). ↩︎

-

Translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. “Ma quale sigillo da perfezione formale, quale felice complicità dell'occhio e del compasso; e che dialogo sottile, solitario, tra forma colma voltata nello spazio, e il taglio del profile!” Carlo Volpe, “Paolo Uccello a Bologna,” Paragone, vol. 31, no. 365 (July 1980), 3–28, in particular 16. Franco and Stefano Borsi, Paolo Uccello (Milan: Leonardo, 1992). ↩︎

-

Alessandro Angelini, after 1434 (1990); Miklós Boskovits, about 1430–1435 (1997, 2002, and 2003); Laurence Kanter, 1440s to early 1450s (2000); Hugh Hudson, early/mid-1440s (2008), and Mauro Minardi, before 1450 (2017)See note 4. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits, “Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Young Man, about 1430-1435,” in Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento, eds. Luciano Bellosi, Lauro Cavazzini and Aldo Galli, exh. cat. Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 20 September-21 December 2002 (Milan: Skira, 2002), 194-6, cat. no. 32. ↩︎

-

According to this letter, it was Everett Fahy who suggested that Boskovits contact the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Letter from Miklós Boskovits to Brett Waller, 27 June 2001, File 2014.87 (C10077), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Roskill had been in contact with Fahy at the time the painting was sent to the Fogg for analysis. Mark Roskill, “Clowes Collection Catalogue” (unpublished typed manuscript, IMA Clowes Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN, 1968). Also see notes 40–41. ↩︎

-

“…che per alcuni aspetti ‘costringe’ ad una percezione di incredibile modernità, tale da non esorcizzare completamente i sospetti di non autenticità che in maniera più o meno larvata l'hanno da sempre accompagnata.” Angelo Tartuferi, “La mostra ‘Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento’ a San Giovanni Valdrano,” Gazzetta antiquaria, vol. 42, no. 2 (November 2002): 34–39, in particular 39. ↩︎

-

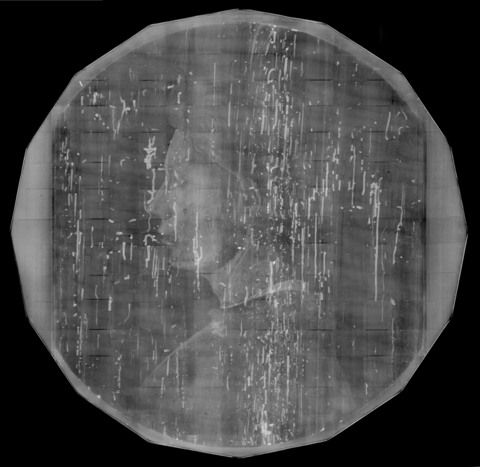

David Miller, condition report C10077 (2014.87), 10 December 2001, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

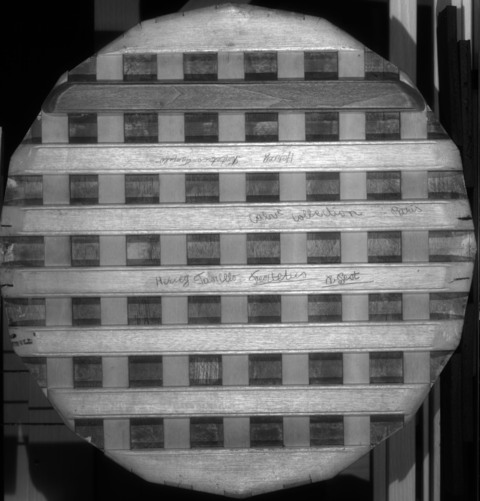

While a tondo is a highly unusual choice for a portrait, see the entry on Portrait of Hans Holbein after Hans Holbein the Younger in this catalogue. Roberta J. M. Olson, “Lost and Partially Found: The Tondo, a Significant Florentine Art Form, in Documents of the Renaissance,” Artibus et Historiae 14, no. 27 (1993): 31–65. Circular and polygonal panels are associated with a type of object known as a desco da parto, a gift tray related to childbirth. These objects were typically embellished with family coats of arms, putti, scenes of motherhood, and moral exemplars. Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, “The Medici-Tornabuoni Desco da Parto in Context,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 33 (1998): 137–51, in particular 143. The elaborate polygon, a hexadecagon, is a fitting nod to Uccello’s fascination with multifaceted forms such as the mazzocchi. ↩︎

-

Boskovits misspells Gavet as “Gravet”. Miklós Boskovits, “Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Young Man, about 1430–1435,” in Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento, eds. Luciano Bellosi, Lauro Cavazzini and Aldo Galli, exh. cat. Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 20 September–21 December 2002 (Milan: Skira, 2002), 194. ↩︎

-

“Portrait d’homme, École Ombrienne, fin du xve, siècle, Le personnage, un jeune homme imberbe, dont le visage est encadré de longs cheveux bouclés que coiffe un bonnet à bords étroits, est vu à mi-corps. Vêtu d'un pourpoint vert somber muni d’un petit collet brodé d'or et de manches vert clair, il tourne la tête vers la droite et la renverse, la bouche dans une attitude extatique. Fond vert somber. Panneau de chêne, Diam. 0, 47.” P. Chevalier, Catalogue des objets d’art et de haute curiosité de la Renaissance, tableaux, tapisseries, composant la collection de M. Emile Gavet: vente à Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, 31 mai–9 juin 1897 (Paris: Mannheim, père et fils, 1897), 194, cat. no. 756, aBottom of Formccessed 26 January 2022, https://babel.hathitrust.org

/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101068043866;view=1up;seq=13; also see an annotated copy of the accompanying sales list. P. Chevalier, Catalogue des objets d’art et de haute curiosité de la Renaissance, tableaux, tapisseries, composant la collection de M. Emile Gavet: vente à Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, 31 mai–9 juin 1897 (Paris: Mannheim, père et fils, 1897), 73, cat. no. 756, accessed 26 January 2022, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k12451012. The sale included two Milanese portraits (one male and one female), each on a twelve-sided panel. Chevalier, Catalogue (1897), 190, nos. 739–40. These may indicate a taste for polygonal-shaped portraits, but whether or not the format was original or a modification is not known. Their descriptions correspond with images of paintings linked to Gavet’s collection found in the Photo Archive of the Fondazione Federico Zeri, accessed 6 February 2018, http://catalogo.

fondazionezeri.unibo.it/ricerca.v2.jsp?locale=it&decorator=layout_resp&apply=true&percorso_ricerca=OA&filtroprovenienza_OA=8105%7C6499&sortby=LOCALIZZAZIONE&batch=10. Many thanks to Dóra Sallay, Curator of Italian Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, for drawing this to my attention. These two panels appear to relate to a type of portrait bust used to decorate tavolette (ceiling panels). Rebecca Norris, “Beyond the battlefield: Venice’s condottieri families and artistic patronage—The Colleoni of Bergamo, Martinengo di Padernello of Brescia and the Savorgnan del Monte of Udine (1450–1600)” (PhD diss., Cambridge University, 2014), 50–53. This pair corresponds to object nos. 818–819 listed in Gavet’s earlier Collection Catalog (1889) along with a second pair of portraits that were also on twelve-sided panels. Émile Molinier, Collection Emile Gavet: catalogue raisonné précédé d’une et́ude historique et archéologique sur les oeuvres d’art qui composent cette collection (Paris: Imprimerie de D. Jouaust, 1889), 191–92, nos. 815–816 and 818–19, accessed 26 January 2022, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6475154j/. ↩︎ -

See “Distinguishing Marks” section of the Technical Examination Report. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits, “Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Young Man, about 1430–1435,” in Masaccio e le origini del Rinascimento, eds. Luciano Bellosi, Lauro Cavazzini and Aldo Galli, exh. cat. Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, Italy, 20 September–21 December 2002 (Milan: Skira, 2002), 194. The Festetics family seat until 1944 was Keszthely Castle in Hungary. Inventories for the castle are in the Hungarian National Archives: October 1782, MNL OLP 236–9, no. 1 (box 91, fol. 506–577); 1866/1872, MNL OL P 236–9 (vol. 98, fol. 378–94); 1911, MNL OL P 236–9, no. 1 (box 94, fol. 692–703). The descriptions are too general to provide a specific identification for the paintings. I am grateful to Ágota Varga for bringing these to my attention. Email communication between Rebecca Norris and Ágota Varga, 11 May 2018. ↩︎

-

To clarify, there are two copies of the same oversized gelatin print, a type widespread since the 1870s. Each is housed within its respective archive within the National Gallery of Art Library in Washington, DC. René Huyghe Archive, File #DLI00016195: “Uccello (per Fahy visit 2003) / 57 x 47 cm / Italie XVIe; Faux” / Duveen Brothers, Inc. 25, Place du Marché Saint-Honoré, 25 Paris-1er [stamp]; and George Richter Archive, File #DLI165005391: “Uccello (per Fahy visit 2003 / 0 m 57 cm x 0 m 47 cm / Probably hoped to look like Castagno or Uccello / Duveen Brothers, inc. 25, Place du Marché Saint-Honoré, 25 Paris-1er [stamp]. The Richter Archive was gifted to the National Gallery of Art in 1943. Many thanks to Melissa Beck Lemke for her assistance with the photographic collection. Email communication between Rebecca Norris and Melissa Beck Lemke, Image Specialist for Italian Art, Library Image Collections, National Gallery of Art, email correspondence, 8 May 2018. ↩︎

-

George Richter Archive, File# DLI44214755(full view image): “Italian School, 15th C. / Uccello (per E Fahy visit 2003)"; and File# DLI42214828 (detail image): “Italian School, 15th century / Uccello (per E Fahy visit 2003)”. ↩︎

-

Letter from William Suida to Mr. Silberman, 10 September 1941, File 2014.87 (C10077), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Hans Tietze to Mr. Silberman, 27 June 1941, File 2014.87 (C10077), Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letters from Allen Clowes to Daniel Goldreyer, 20 February 1962, 20 July 1962, and 29 November 1962; letter Daniel Goldreyer to Allen Clowes, 22 February 1962; and letter Pauline Murphy to Daniel Goldreyer, 19 February 1962, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Photo negative in an envelope labeled “after Goldreyer restoration Spring 1963,” Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

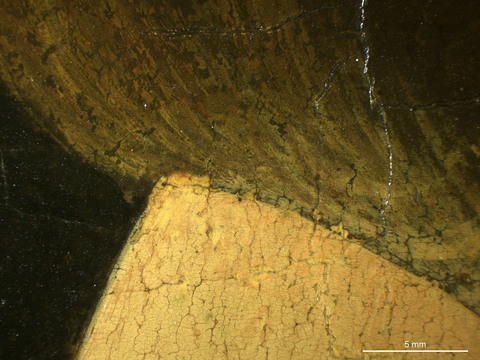

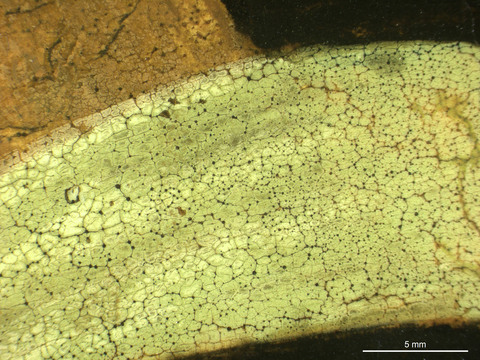

David Miller, condition report, C10077 (2014.87), Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Conservation treatment has been limited to light surface cleaning. See also conservation notes and treatment report, 1990, C10077 (2014.87), Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.. ↩︎

-

David Miller, condition report, C10077 (2014.87), Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.. Abrasion and inpainting are visible in photomicrographs taken from areas at the eye, mouth, and forehead. Photomicrography and analysis by Erica Schuler, Clowes Fellow in Paintings Conservation, June 2017. ↩︎

-

Painting information given here is taken from the website of the holding institution. National Gallery of Victoria, “Saint George Slaying the Dragon, c. 1430 (2124-4),” accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/3747/; Hugh Hudson, “A Knight in Shining Armour, a Virgin—Uccello’s Melbourne Saint George and the Dragon and Oxford Annunciation,” Art Journal 46 (National Gallery of Victoria, 2006), accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/a-knight-in-shining-armour-a-virgin-uccellos-melbourne-saint-george-and-the-dragon-and-oxford-annunciation/; and Hugh Hudson, “The Materials and Technique of Two Panel Paintings Attributed to Paolo Uccello: The Oxford Annunciation and the Melbourne Saint George,” La Peinture Ancienne et ses Procédés: Copies Répliques, Pastiches, Colloque XV, Bruges, 11–13 September 2003, ed. Hélène Verougstraete and Jacqueline Couvert (Leuven, Paris, and Dudley, MA: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2006), 6–17. On The Hunt in the Forest see Ann Massing and Nicola Christie, “The Hunt in the Forest by Paolo Uccello,” The Hamilton Kerr Institute, n. 1 (1988): 30–47; Martin Kemp, Ann Massing, Nicola Christie, and Karin Groen, “Paolo Uccello’s ‘Hunt in the Forest,'” The Burlington Magazine (March 1991): 164–78; and Catherine Whistler, Paolo Uccello’s The Hunt in the Forest (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2001). ↩︎

-

XRF analysis was conducted by Gregory Dale Smith with David Miller and Rebecca Norris, 27 November 2017. ↩︎

-

Silvia A. Centeno, Jaclyn Catalano, Cecil Dybowski, Nicholas Zumbulyadis, Yao Yao, and Anna Murphy, “Investigating the Formation and Structure of Lead Soaps in Traditional Oil Paintings,” accessed 27 October 2017, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/conservation

-and-scientific-research/projects/lead-soaps. Also see Marine Cotte, Emilie Checroun, Wout De Nolf, Yoko Taniguchi, et al., “Lead soaps in paintings: Friends or foes?,” Studies in Conservation 62, no. 1 (2017): 2–23, accessed 28 February 2018, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi

/full/10.1080/00393630.2016.1232529. ↩︎ -

Jill Dunkerton and Ashok Roy, “Uccello’s Saint George and the Dragon: Technical Evidence Re-evaluated,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 19 (1998): 26–30. Ashok Roy and Dillian Gordon, “Uccello’s Battle of San Romano,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 22 (2001): 4–17. ↩︎

-

Ashok Roy and Dillian Gordon, “Uccello’s Battle of San Romano,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 22 (2001): 4–17, in particular 9. Painting information given here is taken from the website of the holding institution. National Gallery, “Saint George and the Dragon, about 1470 (NG6294),” accessed 26 January 2022, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/paolo-uccello-saint-george-and-the-dragon. ↩︎

-

In an undated expertise, probably from the early 1940s, Lionello Venturi identifies the painting as having been in the “Emile Gavet Collection, Paris, about 50 years ago.” Several French customs stamps appear on the back of the painting. ↩︎

-

The name “Taszillo Fesztetics [sic] B Pest” is written in pencil on one of the stretcher bars. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits refers to the existence of a photograph stamped “Duveen Brothers Inc., Paris” in the Richter Archive of Illustrations of Art at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; see his contribution to Luciano Bellosi et al., eds., Masaccio e le origini del Rinasciemento (Milan: Skira, 2002) no. 32, 194–196. ↩︎

-

A cancelled check made out to E. & A. Silberman, in payment for a painting by Uccello, is dated 12 November 1942; see File: Packet of checks, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎