Overview

Accession number: 2000.341

Artist: Giovanni Bellini and Workshop

Title: Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist

Materials: Egg tempera and oil (untested) on poplar panel

Date of creation: About 1490–1500

Previous number/accession number: C10004

Dimensions: 76.2 × 58.4 cm

Conservator/examiner: Roxane Sperber and David Miller

Examination completed: 2019

Distinguishing Marks

Front:

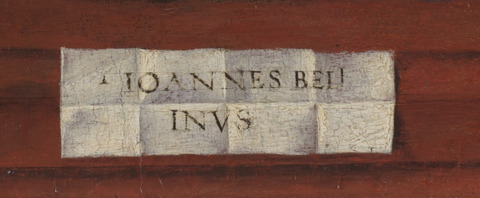

Item 1. Signature “IOANNES BELI/INVS” (tech. fig. 1).

Back:

Item 2. Customs stamp “Schw…. Zo….t Buch.. ✚/ 10 X 33” probably “Schweiz Zollamt Buchs ✚ / 10 X 33”

Item 3. Seal with crest (tech. figs. 3, 4).

Summary of Treatment History

Historical documents provide information about the physical history of the painting. A photograph from 1932 (tech. fig. 5) shows the painting in black and white, and letters between Dr. Clowes and restorer Roman C. Diorio confirm that the painting was treated by Diorio in 1941. Clowes was concerned that the cleaning not damage the painting, writing, “I am confident that I can bank on you not to clean the picture too much. If in doubt, I should certainly prefer to leave some of the over-painting, rather than reduce the picture to the state of some of those that I recently saw in the Kress collection.” He goes on to state:

“I believe from the x-rays that you really have a splendid Bellini foundation on which to work and I am trusting you not to spare time, effort, or expense to give me the best possible job that you or anyone else can accomplish with this particular picture. If you accomplish as good a result as you believe you can, it will certainly be most satisfactory for you as well as for me, as one or two people who have looked the picture over have been hesitant about the prospects of cleaning it, even though they recognize that large areas were unquestionably by Bellini. If you can get a good result on this picture, I shall not fail to inform those who see it that you undertook the job."1

Diorio responds:

“The painting has suffered a little, particularly in the white zone of the sky, which seems as if some one [sic] not caring for the original ivory-color went over over [sic] the surface with sandpaper thereby smoothing the color down to the white. The cherubins [sic] have suffered most of all due to the little resistance (having been painted with a very thin glaze) to the powerful solvent which has been used in the past, as the photos taking during and after cleaning will show.

In spite of all this the painting has improved to such a great extent that the return of the transparency of the original colors make you feel that you have before you a different painting. With the exception of two or three minor damages on the face of the Madonna and children, those vital part of the painting are in the best sate [sic] of preservation."2

It appears that, upon delivery to the Clowes residence, some sort of accident happened to the painting. On 9 September 1941, Clowes wrote to Diorio to say he had shipped the painting to California where Diorio was working at the Los Angeles Couty Museum. Clowes alluded to the damage, noting, “I sincerely hope that you have been able to take care of the damage done by Adrien’s [the butler’s] mistakes."3 On October 19, Diorio replied that he had “cleaned the Bellini and removed all the Adrian’s damage."4

A historical document written by William Suida describes the coloration of the angels differently in 1932 than in 1948, when he references how a cleaning affected the appearance of the work. An article by Erika Tietze-Conrat, published in 1948, also references the recent cleaning. She described viewing the work “when it was free of every touch of overpaint."5 David Miller observed that the 1932 image shows the modeling of the skin in the cherubs, now highly damaged, looking more consistent with Bellini’s technique and style than the appearance of the painting before the 2001 treatment (tech. fig. 6).6 It is possible that the twentieth-century treatment damaged the delicate modeling that was, until then, present on the work.

Documentation indicates a series of condition assessments and treatments were carried out on the collection about the time the works were moved from the Clowes residence to the IMA in 1971. A condition report by Paul Spheeris in October of that year, likely carried out before the paintings were relocated, described the painting as “O.K.” but that the frame was fragile and chipped. No treatment was recommended at that time.7 A second condition assessment was carried out upon arrival of the paintings at the IMA. This assessment describes the work as being in stable condition and no treatment was deemed necessary.8

In 1974, a condition assessment, treatment, and investigation of the collection was carried out by the Intermuseum Conservation Association at Oberlin College. This document describes this painting as having been recently cradled and having a vertical split extending 14-1/2 inches from the bottom edge. The surface coating is described as a moderately thick, somewhat uneven natural resin varnish with overpaint in the sky and seraphim. Treatment to reinforce the split with balsa wood was proposed.9

A technical study and full treatment to remove layers of darkened varnish and discolored overpaint and to reintegrate the image through inpainting was carried out at the IMA from 2001 to 2004 by David Miller and Linda Witkowski.10 A multifaceted cleaning approach using solvent gels and free solvents was adopted to remove the multiple layers of varnish and overpaint. A solvent mixture of acetone, diacetone alcohol, and benzine (30:30:40) was used to swell the thick layer of varnish and slowly remove it (tech. fig. 7). Pure acetone was used in particularly insoluble areas of varnish. A free solvent application of diacetone alcohol or propanol was used to clear residual varnish. In areas where paint sensitivity was of concern, the repeated application of propanol was used to slowly dissolve the varnish. A solvent gel containing xylene and benzyl alcohol was used to swell and remove the majority of the overpaint. The gel was cleared using xylene and/or propanol. N,N-dimethylformamide diluted with xylene was used locally to remove aged oil overpaint (tech. fig. 8).

Losses were filled with Polyfix for shallow losses and gilder’s whiting and gelatin 10% in water for deeper losses, and the painting was varnished with Paraloid B-72 and Regalrez 1094. Inpainting was carried out using Gamblin Conservation Colors (see Description of Varnish/Surface Coating)

The painting was inspected in the Clowes Collection annual survey from 2011 to 2018.

Current Condition Summary

The painting is in stable condition and has remained aesthetically integrated since the treatment in the early 2000s. Some surface dirt has accumulated on the painting, but the work is in otherwise good condition.

Methods of Examination, Imaging, and Analysis

| Imaging | Surface analysis (no sample required): | Analysis (sample required): |

|---|---|---|

| Unaided eye | Dendrochronology | Microchemical analysis |

| Optical microscopy | Wood identification | Fiber ID |

| Incident light | Microchemical analysis | Cross-section sampling |

| Raking light | Thread count analysis | Dispersed pigment sample |

| Reflected/specular light | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) |

| Transmitted light | Macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (MA-XRF) | Raman microspectroscopy |

| Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UV) | ||

| Infrared reflectography (IRR) | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) | |

| Infrared transmittography (IRT) | Scanning electron microscope -energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) | |

| Infrared luminescence | Other: High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), UV micro spectrofluorometric analysis | |

| X-radiography |

Technical Examination

Description of Support

Analyzed Observed

Material Type (fabric, wood, metal, dendrochronology results, fiber ID information, etc.):

The painting is on a single poplar (Populus ssp.) panel (tech. fig. 9).11 The original panel has been thinned to 0.7 cm revealing minor woodworm damage. There does not appear to be a layer of canvas present on the panel, as is often found on Italian panels and appears to be present on the Workshop of Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child.

Characteristics of Construction/Fabrication (cusping, beveled edges of panels, seams or joins, battens):

The panel appears to be constructed from a single, vertically oriented board that is 59 cm wide. Single boards measuring 60–70 cm or wider were occasionally used in the construction of Italian paintings, although 20–40 cm is the more common width.12

Thickness (for panels or boards):

The original panel has been thinned to 0.7 cm. The panel and cradle are 3 cm thick.

Production/Dealer’s Marks:

None

Auxiliary Support:

Original Not original Not able to discern None

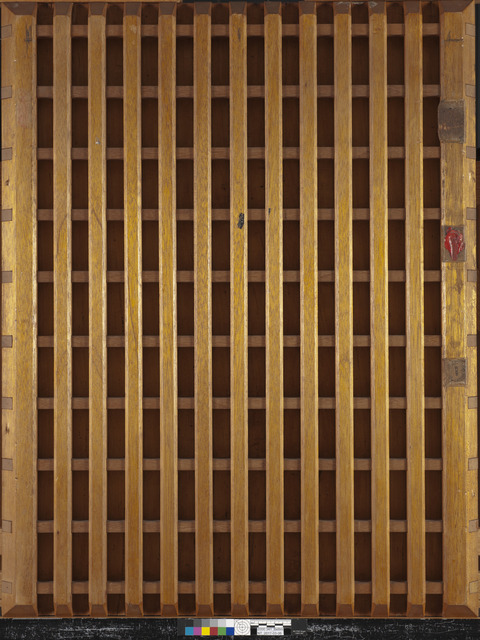

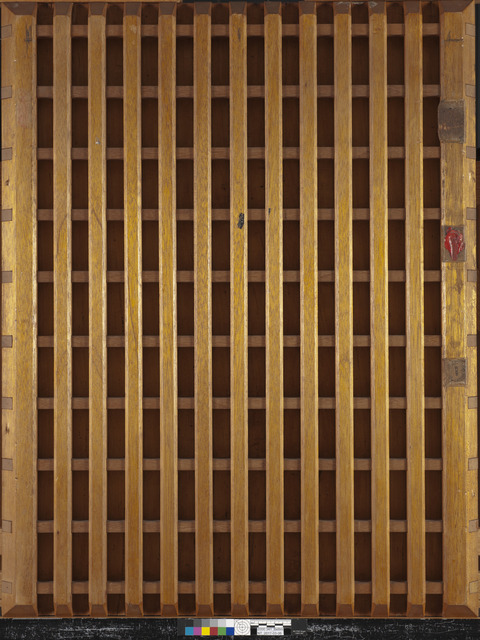

A 23-member cradle, with 13 fixed vertical members and 10 horizontal movable members, has been attached to the back of the thinned panel (tech. fig. 10). One of the horizontal members has seized and can no longer slide.

The cradle is well-crafted. It has beveled edges and is adhered to the thinned panel with an adhesive. The outer vertical members are 4.5 cm wide, and the inner vertical members are 2 cm wide. The horizontal members are 1.5 cm wide.

On the right vertical member three wooden inlays have been nailed into notches in the cradle. Two of the inserts have identifying marks, and those pieces may have been transferred from a previous cradle (see Distinguishing Marks).

Weave (structure, weight, thread thickness, etc):

N/A

Condition of Support

Both the original support and auxiliary support are stable and in good condition. There is a crack in the panel 14.5 cm from the left side extending from the bottom edge up 48 cm through the panel. There is a hairline crack 20 cm from the right side of the panel extending approximately 17 cm up from the bottom edge of the panel. There is minor, old woodworm damage that was exposed when the panel was thinned.

Description of Ground

Analyzed Observed

Materials/Binding Medium:

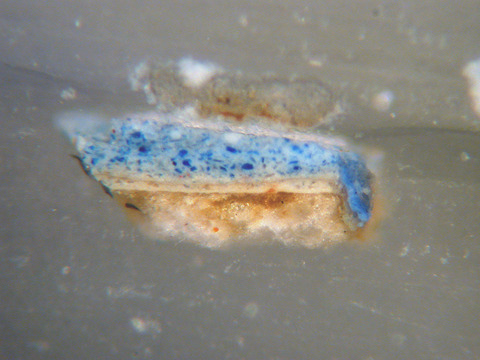

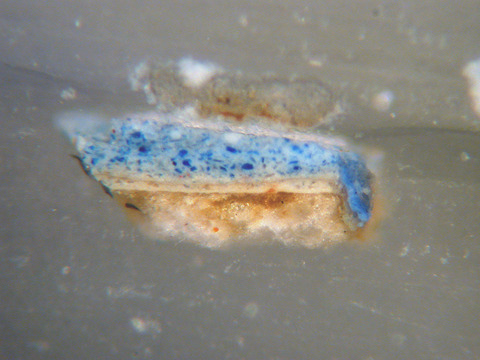

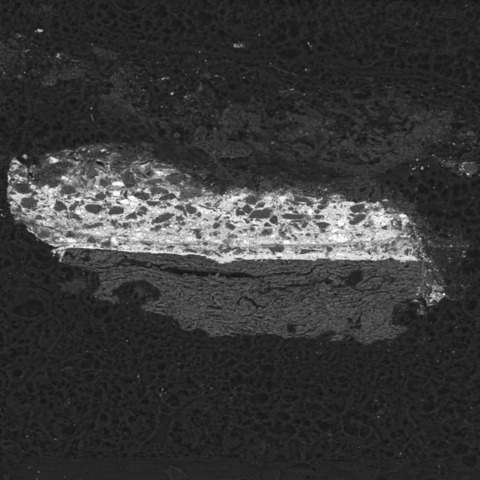

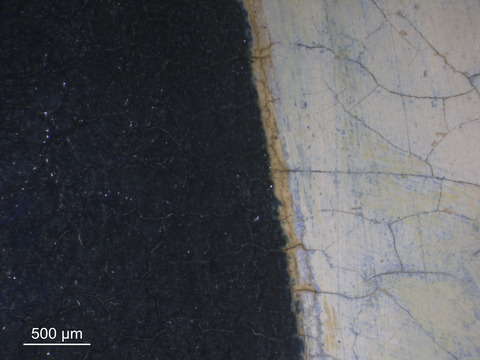

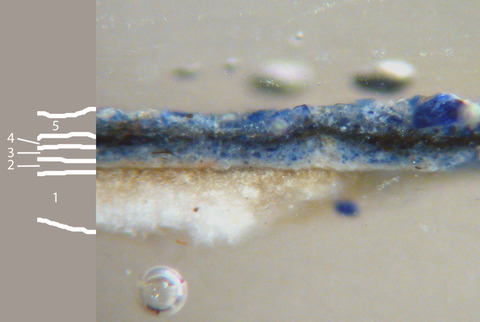

The painting has a gesso ground composed of calcium sulfate in its double-hydrated form (gypsum) (tech. fig. 11). The panel was sized with an organic coating before the application of the gesso.13 There does not appear to be a consistent imprimatura across the painting, however localized underpainting is present as part of the buildup of paint layers.14

Color:

The gesso ground is off-white in color. Layers of underpaint present in localized areas of the composition are composed of primarily lead white with the addition of some pigment to tone the areas (tech. figs. 12, 13). A similar technique has been observed on numerous paintings by Bellini and his workshop.15

Application:

Cross sections indicate that the ground was applied in two distinct layers (tech. fig. 11). Layers of toned underpaint are applied locally and vary from area to area.

Thickness:

The ground is thick and evenly applied. Layers of underpaint are thinly applied over the ground (tech. fig. 12).

Sizing:

Previous research noted a layer of organic material applied to the panel under the first application of ground.16 A second sizing layer composed of organic medium was also applied over the ground layer to reduce absorbency and can be observed partially penetrating the ground layer in the cross section.

Character and Appearance (Does texture of support remain detectable/prominent?):

The texture of the panel is generally smooth. Texture appears to come from upper layers of paint rather than the ground, suggesting the ground was smoothed before paint layers were applied.

Condition of Ground

The ground is in generally stable condition. Extensive damage to the paint layer does not appear to have affected the ground, which is still intact across most of the picture plane.

Description of Composition Planning

Methods of Analysis:

Surface observation (unaided or with magnification)

Infrared reflectography (IRR)

X-radiography17

Analysis Parameters:

| X-Ray equipment | GE Inspection Technologies Type: ERESCO 200MFR 3.1, Tube S/N: MIR 201E 58-2812, EN 12543: 1.0mm, Filter: 0.8mm Be + 2mm Al |

|---|---|

| KV: | 26 |

| mA: | 3.0 |

| Exposure time (s) | 120 |

| Distance from x-ray tube: | 36” |

| IRR equipment and wavelength | Opus Instruments Osiris A1 infrared camera with InGaAs array detector operating at a wavelength of 0.9-1.7µm. |

Medium/Technique:

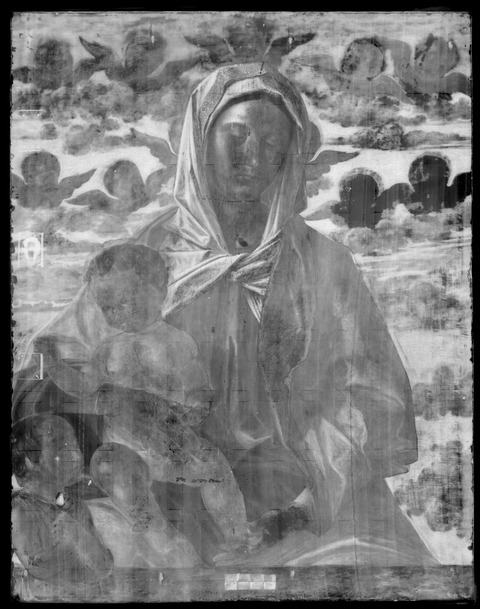

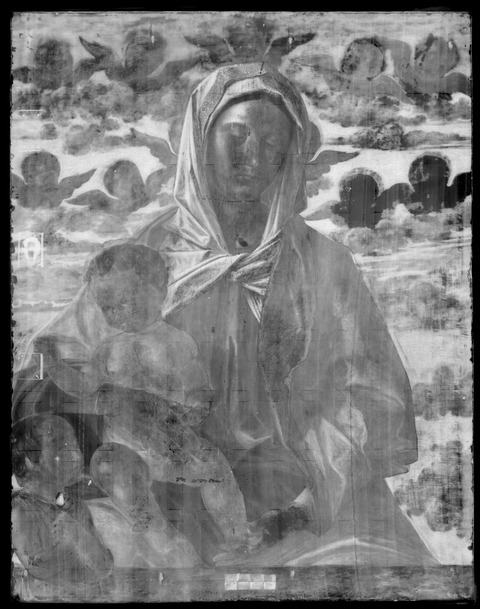

The composition of the painting follows a standard Madonna type from the Bellini workshop that was reproduced countless times (see Catalogue Entry). Cartoons were frequently used to transfer the outlines of standard compositions, and evidence of this transfer can be found on Madonnas from the Bellini workshop in the form of pouncing or carefully executed underdrawing (an example of this can be seen on the Workshop of Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child).18 The contours of the Madonna and child on Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist closely follow that of other versions of the painting, demonstrating that it almost certainly originated from the same source as these other works. However, infrared reflectography reveals no evidence of the transfer technique used on this painting (tech. fig. 14). It is possible that underdrawing was executed in a medium that is not infrared absorbent, such as red chalk, but this cannot be confirmed.

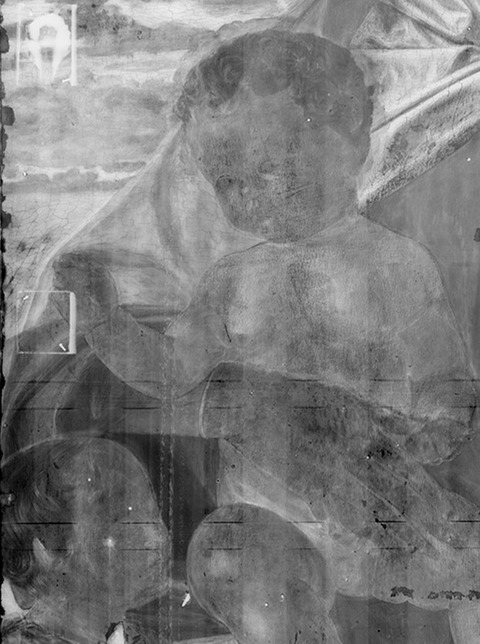

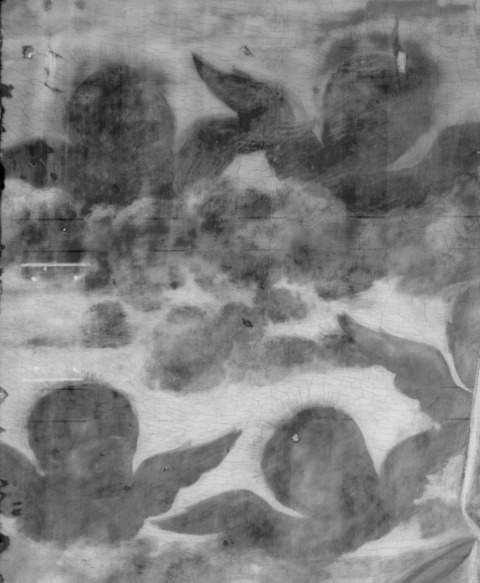

Incision lines do appear to be present in several areas of the figure and may have been used to transfer the composition (tech. fig. 15).19 Incision lines are also visible around the heads of the angels in the 2001 during treatment photograph (tech. fig. 16) and the X-radiograph (tech. fig. 17), suggesting a previous iteration of the composition where the angels were depicted with beams of light coming out of the heads to form halos. Much damage has occurred in these areas making it difficult to imagine the original appearance. However, original paint from the sky does extend over the halos of two angels that were not completely abraded (tech. fig. 16), suggesting the artist changed the design during the painting phase. An early example of a similar halo with incised rays of light can be found on the Trittico delle Madonna housed in the Galleria dell’Academia in Venice. In this example, the background was gilded and the halo tooled.20

Additionally, changes to several elements of the composition are visible in the X-radiograph (tech. fig. 15). A reserve was originally left for the head of the Christ child and St. John the Baptist that were later changed (see Description of Paint).21

Description of Paint

Analyzed Observed

Application and Technique:

Although the method used to transfer the image to the panel is impossible to know for sure, it is abundantly clear from the order of paint application that the composition of the work was carefully determined before painting began. The paint was applied in defined forms clearly following the preplanned composition.

Reserves were used throughout the painting and in some cases a small gap was left between one passage of color and another (tech. figs. 18, 19).22 The Madonna appears to have been painted first, leaving a reserve for the child. The application of paint in the robe is remarkably thick, in part perhaps due to the coarse nature of the precious natural ultramarine pigments.

The precision and planning extend to the drapery of the figures as well. Each highlight and shadow are mixed and applied—suggesting the artist did not glaze the shadows as was sometimes the case when using an oil medium. This may be a feature of this early oil/mixed technique where the artist was experimenting with how oil and tempera could complement each other. Regardless, it is clear that the shapes of the drapery were planned in advance, and the shadows and highlights were applied directly. Some blending occurred at the edges to create a delicate, fluid technique.

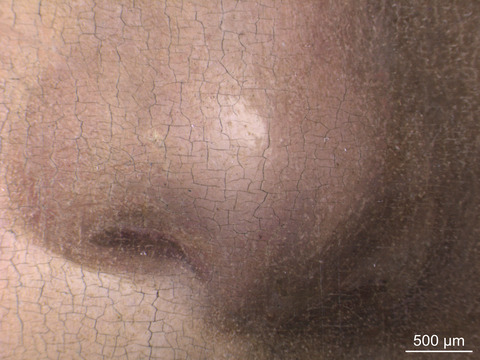

The skin was also painted using carefully defined areas of light and shadow that were then blended to create a smooth transition of soft tones. A carefully articulated dab of light paint was added to the tip of the Madonna’s nose to create the brightest highlight and masterfully create the illusion of form (tech. fig. 20). Sadly, the delicate glazes that were certainly present in the face have since been largely abraded.

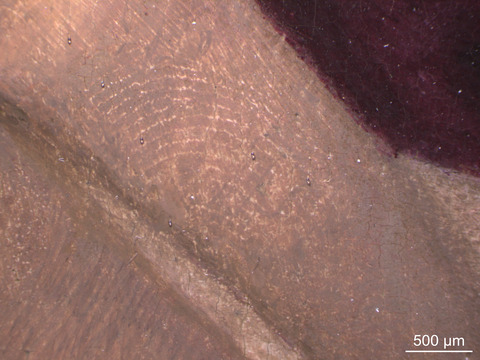

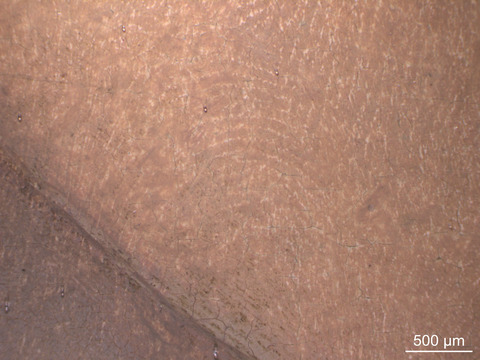

Much like on the Clowes Madonna and Child (2000.342), fingerprints can be found in the paint of the skin suggesting the artist (or artists) manipulated the paint with their hands to create the soft transitions of highlight to shadow in these areas (tech. figs. 21, 22).23 A similar effect is present in the cloud to the right of the Madonna’s head, where it appears the artist used his palm to create a dappled light effect on a cloud (tech. fig. 23).

The Christ child was painted after the Madonna, extending just over the edge of the reserve. The initial reserve for the child’s head was at some point in the painting stage deemed too small, and the child’s head was enlarged with more abundant curls (tech. fig. 15). It is clear that the parapet was painted before St. John, as it can be seen extending beneath the boy’s body in the X-radiograph (tech. fig. 9). It has been argued that the technique used on St. John was considerably less adept than in other areas of the painting, suggesting it may have been a different hand.24 Curiously, there does seem to have been a rough reserve left for the body of St. John, as the robes of the Madonna do not extend underneath the figure. The order of painting suggests that this figure was not an afterthought, and if it was painted by a different hand, the panel would have been handed off to an apprentice in the middle of the painting stage.25 Much like the reserve left for the Christ child’s hair, the hair of St. John appears to have been originally intended to be quite short but was later lengthened to his chin.

The sky and angels are painted around the Madonna, suggesting they were added after the figures. Although severely abraded, it is clear from what remains of the fragmentary angels that bright, vibrant pigments were used in these areas of the painting.

Painting Tools:

Small to medium-sized brushes, fingers, and palm of hand

Binding Media:

Analysis of binding media by Antonietta Gallone and Cinzia Mancuso was carried out on selected cross sections using ultraviolet microspectrofluorometry in preparation for a 2004 publication. This research identified a mixed media of egg and oil.26

Color Palette:

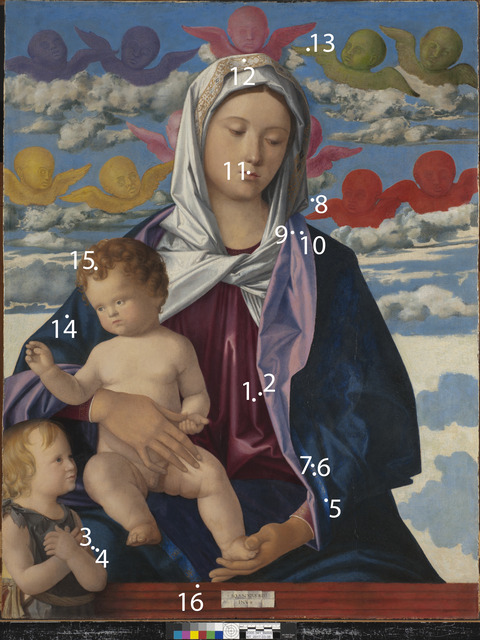

The color palette is composed of bright blues, reds, greens, pinks, and yellows. Cross-section analysis using SEM/EDS was carried out on individual pigments. According to Gallone and Mancuso, lead white, lead-tin yellow, yellow ochre, natural ultramarine, azurite, red lake pigments, cinnabar, copper resinate, brown ochre, earth pigments, carbon black, and bone black were identified in the palette of the painting.27 XRF analysis was performed in 2019 to get a broader understanding of the pigments used (tech. fig. 25). Unfortunately, XRF was not available when the painting was being treated, therefore it was necessary to avoid areas of inpainting, limiting the opportunities for analysis.

XRF analysis suggested the presence of lead white, a calcium-containing ground (as was confirmed by Gallone and Mancuso using X-ray diffraction),28 vermilion, yellow ochre, lead-tin yellow, and a copper-containing green pigment. Analysis by Gallone and Mancuso confirmed the use of natural ultramarine in the Virgin’s robe, and a cross-section from this area determined the mantle to have been painted using several layers of natural ultramarine mixed with varying amounts of lead white (tech. fig. 24).29

XRF analysis of the bright blue sky also detected only trace amounts of copper, suggesting the use of natural ultramarine in this area of the painting as well. This is consistent with previous studies of Bellini’s painting, which found that in all instances in which ultramarine was identified in the Madonna’s mantle, it was also found to have been used in the sky.30

Cross-section analysis by Gallone and Mancuso identified a small amount of azurite, mixed with lapis lazuli and lead white, in the sky. One would expect such a pigment mixture to yield a stronger signal for copper in XRF, but this was not the case. Perhaps the XRF analysis was carried out in an area where the mixture of azurite was especially minimal. Regardless, the widespread presence of natural ultramarine in this painting is undeniable. Few measures were taken by the artist to minimize expenditures, suggesting the commission was for a wealthy and important patron.

In the Virgin’s bodice, the use of red lake pigments can also be inferred by the absence of mercury or iron. The only elements detected in this rich, red passage were lead and minimal traces of calcium, iron, potassium, copper, and zinc (from inpainting). It is impossible to say what the substrate for this lake pigment would have been from XRF. No aluminum was detected and the peak for calcium is not stronger in these areas than in other areas of the painting where the calcium ground is detected. Analysis by Gallone and Mancuso identified the red lake pigment as cochineal using HPLC and FTIR.31

Decorative elements on the Virgin’s mantle appear to have been painted using a combination of yellow ochre and vermilion, with a similar combination used to paint the Christ child’s hair. The presence of tin was not detected in these areas, although a peak for tin was present in the green angel, suggesting the presence of lead-tin yellow in that area. Analysis of the wing of the green angel was the only XRF sample location where a strong peak for copper was found, suggesting lead-tin yellow and copper-resinate/oleate were used in this area. Care was taken to avoid areas of inpainting; however, the angels were severely abraded making analysis of original paint especially difficult.

XRF Analysis:

| Sample | Location | Elements | Possible Piments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Highlight on red bodice | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Cu, Ca, Zn, Fe, Sr, K | Lead white, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium (likely from ground), trace of zinc (likely from inpainting). |

| 2 | Shadow on red bodice | Major: Pb Minor: Cu, Zn Trace: Ca, Fe, Sr, K | Lead white, copper containing green and/or blue pigment, zinc (likely from traces of inpainting), trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 3 | Bright blue underlayer of robe | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Cu, Zn, Ca, Fe, Sr, K | Lead white, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of zinc (likely from traces of inpainting), trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 4 | Dark blue of robe | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Cu, Zn, Ca, Fe, Sr, K | Lead white, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of zinc (likely from inpainting), trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 5 | Blue of robe cuff | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Cu, Zn, Ca, Fe, Sr, K | Lead white, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of zinc (likely from inpainting), trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 6 | Red decoration on cuff of robe | Major: Pb Minor: Hg, Fe Trace: Cu, Zn, Ca, Sr, K | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), vermilion, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of zinc (likely from traces of inpainting), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 7 | Yellow decoration on cuff of robe | Major: Pb Minor: Hg, Fe Trace: Cu, Zn, Ca, Sr, K | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), vermilion, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of zinc (likely from inpainting), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 8 | Sky | Major: Pb Minor: Fe Trace: Cu, Zn, Ca, Sr, K | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of zinc (likely from inpainting), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 9 | Highlight of robe lining | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Cu, Zn, Ca, Sr | Lead white, trace of zinc (likely from inpainting), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 10 | Shadow of robe lining | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Hg, Zn, Ca, Sr, K, Fe | Lead white, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of zinc (likely from inpainting), trace of vermilion, trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 11 | Madonna’s lip | Major: Pb Minor: Hg Trace: Zn, Ca, Sr, K, Fe | Lead white, vermilion, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of zinc (likely from traces of inpainting), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 12 | Yellow decoration on headdress | Major: Pb Minor: Hg Trace: Fe | Lead white, vermilion, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments). |

| 13 | Green putti | Major: Pb, Cu Minor: Trace: Fe, Sn, Ca, Sr | Lead white, vermilion, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of lead-tin yellow, trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 14 | Blue robe proper right shoulder | Major: Pb Minor: Trace: Fe, K, Ca, Zn | Lead white, trace of iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of zinc (likely from inpainting), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 15 | Highlight on hair of Christ child | Major: Pb Minor: Hg, Fe Trace: Cu, Zn, Ca | Lead white, iron oxide (earth pigments), vermilion, trace of copper containing green and/or blue pigment, trace of zinc (likely from inpainting), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

| 16 | Red parapet | Major: Pb, Hg Minor: Fe Trace: Ca | Lead white, vermilion, iron oxide (earth pigments), trace of calcium (likely from ground). |

Table 1: Results of X-ray fluorescence analysis conducted with a Bruker Artax microfocus XRF with rhodium tube, silicon-drift detector, and polycapillary focusing lens (~100μm spot).

*Major, minor, trace quantities are based on XRF signal strength not quantitative analysis

Surface Appearance:

The surface is relatively smooth, with some minimal texture from short brushstrokes. The thick buildup of paint is visible in raking light along the edges of distinct areas of color.

Condition of Paint

The paint layer is in stable condition; however a history of harsh interventions, carried out before the painting was acquired by the IMA, left many areas of the painting in poor condition (tech. fig. 26) (see Summary of Treatment History). While the figures are in fair condition, abrasion is apparent in the skin painting. Severe damage is present in the sky and angels. The 2001 treatment removed previous overpaint and retouching, revealing the damaged nature of the original paint layer (tech. fig. 27). Decisions to reintegrate the image through careful reconstruction using inpainting were taken, allowing the image to be appreciated again.

Description of Varnish/Surface Coating

Analyzed Observed Documented

| Type of Varnish | Application |

|---|---|

| Natural resin | Spray applied |

| Synthetic resin/other | Brush applied |

| Multiple Layers observed | Undetermined |

| No coating detected |

During the 2001 treatment, the painting was varnished with a multilayered system. After the removal of the Regalrez 1094 temporary varnish, 5% Paraloid B-72 in Cyclosol 53 was locally applied in several applications to saturate the blue robe. A brush varnish of 10% solution of Paraloid B-72 in Cycolsol (shell) 53 was then applied to the entire painting. The painting was inpainted with Gamblin Conservation Colors in propanol (tech. fig. 28). After inpainting, a second brush varnish of 20% Regalrez 1094 in Shell 340HT with 3% w/v of Kraton G 1650 resin and 2% Tinuvin 292 w/v was applied to the entire painting.

Condition of Varnish/Surface Coating

The varnish is in generally good condition, clear, and well saturating. The inpainting is well matched and well saturated. The accumulation of a thin layer of surface dirt has created a slightly matte appearance to a once glossy varnish.

Description of Frame

Original/first frame

Period frame

Authenticity cannot be determined at this time/ further art historical research necessary

Reproduction frame (fabricated in the style of)

Replica frame (copy of an existing period frame)

Modern frame

This wooden tabernacle frame is consistent with those of Renaissance Italy that harkened back to the forms of classical antiquity. The frame has a carved wooden cornice and columns on the left and right sides with gilded capitals (tech. fig. 29). The frieze, columns, and predella are painted with light blue paint. Mordant gilding, now mostly abraded, was used to create floral motifs in these areas (tech. fig. 31). The black mordant is still visible, allowing the decorative elements to be appreciated.

Frame Dimensions:

Outside frame dimensions: 112.7 × 92 × 13.5 cm

Sight size: 74.8 × 57 cm

Distinguishing Marks:

Front

Item 4: Abraded inscription along the top edge (tech. fig. 31).

Back

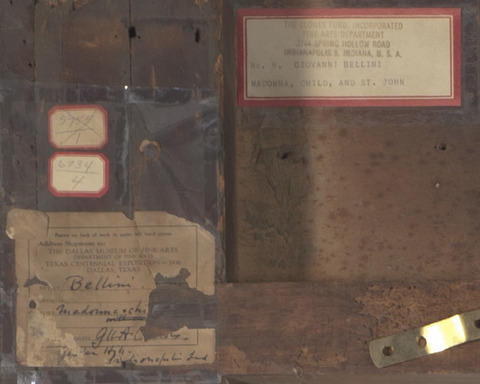

Item 5: Paper label “Clowes Fund Incorporated/ Fine Arts Department/ 3744 Spring Hollow Road/Indianapolis Indiana U.S.A/ No. 5 Giovanni Bellini/ Madonna Child and St. John” (tech. figs. 30, 32).

Item 6: Paper label “5755/1” (tech. figs. 30, 32).

Item 7: Paper label “6734/4” (tech. figs. 30, 32).

Item 8: Paper label from the Dallas Museum of Art (partially damaged) (tech. figs. 30, 32).

Item 9: White label “T.R. # 10004” (tech. fig. 33).

Condition of Frame

The frame is in structurally sound condition. There is some evidence of past woodworm damage (tech fig. 30), but the wood is stable and in good condition. The aesthetics of the frame are also largely intact, with some abrasion to the mordant gilding.

Notes

-

Letter from G.H.A. Clowes to Roman C. Diorio, 2 June 1941, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Roman C. Diorio to G.H.A. Clowes, 3 June 1941, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Roman C. Diorio to G.H.A. Clowes, 9 September 1941, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Roman C. Diorio to G.H.A. Clowes, 19 October 1941, Correspondence Files, Clowes Registration Archive, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Erika Tietze-Conrat, “An Unpublished Madonna by Giovanni Bellini and the Problem of Replicas in His Shop,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 33 (1948): 382. ↩︎

-

David A. Miller, “The Conservation of a Madonna and Child by Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 156. ↩︎

-

Paul A.J. Spheeris, “Conservation Report on the Condition of the Clowes Collection,” 25 October 1971, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Martin Radecki, Clowes Collection condition assessment, undated (after October 1971), Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Intermuseum Conservation Association, “Clowes Collection Conservation Report,” C10004 (2000.341), 8–10 April 1974, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

See David A. Miller, “The Conservation of a Madonna and Child by Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 152–159, and Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 128–151. ↩︎

-

Peter Klein, dendrochronological analysis report, C10004 (2000.341), 20 April 1999, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Luca Uzielli, “Historical Overview of Panel-Making Techniques in Central Italy” The Structural Conservation of Panel Paintings: Proceedings of a Symposium at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 24–28 April 1995, ed. Kathleen Dardes and Andrea Rothe (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Conservation Institute, 1998), 118, http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/panelpaintings. ↩︎

-

Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 139. ↩︎

-

Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 131–132. ↩︎

-

Jill Dunkerton, “Bellini’s Technique” in The Cambridge Companion to Giovanni Bellini, ed. Peter Humfrey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 208. ↩︎

-

Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 139. ↩︎

-

Elvacite 2040 (synthetic resin) was used to fill the cradle while shooting the X-radiograph so that the appearance of the cradle would be minimized in the X-radiograph and allow the composition to be better interpreted. ↩︎

-

Jill Dunkerton, “Bellini’s technique,” in The Cambridge Companion to Giovanni Bellini, ed. Peter Humfrey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 203–205. ↩︎

-

For other examples where incision lines are found on the central part of the composition, see Jill Dunkerton, “Bellini’s Technique,” in The Cambridge Companion to Giovanni Bellini, ed. Peter Humfrey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 205. ↩︎

-

Rosella Bagarotto et al., “La Technica Pittorica di Giovanni Bellini,” in Il Colore Ritrovato: Bellini a Venezia, eds. Rona Goffen and Giovanna Nepi Scirè (Venice, Electa 2000), 188. ↩︎

-

For discussion of this change, see Andrea Golden, “Creating and Re-creating: The Practice of Replications in the Workshop of Giovanni Bellini,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 113. ↩︎

-

The extensive use of reserves in Bellini’s paintings is noted by David Bull in “The Feast of the Gods: Conservation and Investigation,” Studies in the History of Art 45 (1993): 370, https://www.jstor.org/stable/42621892. ↩︎

-

The frequent presence of fingerprints in Italian oil paintings from the fifteenth century is explained by Rosella Bagarotto and others as a result of artists familiarizing themselves with the oil technique. Rosella Bagarotto et al., “La Technica Pittorica di Giovanni Bellini” in Il Colore Ritrovato: Bellini a Venezia, ed. Rona Goffen and Giovanna Nepi Scirè (Venice, Electa 2000), 192. ↩︎

-

Andrea Golden, “Creating and Re-creating: The Practice of Replications in the Workshop of Giovanni Bellini,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 114. ↩︎

-

For further discussion, see Andrea Golden, “Creating and Re-creating: The Practice of Replications in the Workshop of Giovanni Bellini,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 114–15. ↩︎

-

Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 136, 139–140. ↩︎

-

Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 143. ↩︎

-

Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 131. ↩︎

-

Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 133–134. Note the lower ground layer is missing from this cross section. ↩︎

-

Rosella Bagarotto et al., “La Technica Pittorica di Giovanni Bellini” in Il Colore Ritrovato: Bellini a Venezia, ed. Rona Goffen and Giovanna Nepi Scirè (Venice, Electa 2000), 193. ↩︎

-

Cinzia Maria Mancuso and Antonietta Gallone, “Giovanni Bellini and His Workshop: A Technical Study of Materials and Working Methods,” in Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion, ed. Ronda Kasl (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 134. ↩︎

Additional Images